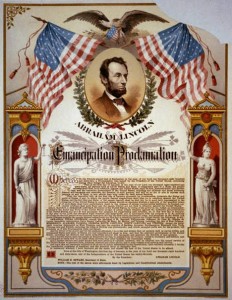

This is another in a series of posts marking the sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation.

No presidential election in American history has been as pivotal as the election of 1860. Had any one of Abraham Lincoln’s three opponents been elected president in November of 1860, South Carolina would clearly not have seceded from the Union on December 20, and it and its six compatriot Deep South states would not have formed the Confederate States of America on February 8, 1861.

(Technically, Texas, one of the seven seceding states, did not join the Confederacy until the first week of March.)

Of course, one of the anomalies of that election was that Abraham Lincoln won a solid majority in the Electoral College, even though he received only 39.7% of the popular vote. The remaining 60+% was divided between the Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas of Illinois (29.5%), the Southern Democrat James Breckenridge of Kentucky (18.2%), and Tennessean John Bell (12.6%), who was the candidate of the Constitutional Union Party, essentially an effort to revive the defunct Whig Party.

While receiving only a plurality of the popular vote, Lincoln nevertheless won a substantial majority in the Electoral College, totaling 180 votes compared to 72 for Breckenridge, 39 for Bell, and only 12 for Douglas.

Although it is often assumed that Lincoln prevailed only because his three opponents split the opposing votes, that was not the case. Because of the way in which Lincoln’s votes were concentrated outside the South, he would have won a majority of votes in the Electoral College even if all of the voters who voted for his three opponents had instead cast their ballots for a single candidate. That candidate would have received 60.3% of the popular vote but would have still lost the Electoral College by a margin of 169 votes to 134.

Given the peculiar distribution of votes, was it possible that Lincoln could have been defeated in 1860?

For that to have happened, there would have had to have been a candidate who could have appealed to both Northern and Southern Democrats and those Whigs and American Party members who did not support the new Republican Party. In other words, such a candidate would first have to hold the votes that went to Douglas, Breckenridge, and Bell.

None of the three actual candidates met this criteria. Douglas’ continued support of popular sovereignty, which would have allowed slavery to be abolished by popular vote in new states carved out of the territories, was perceived by Southerners as inconsistent with the Supreme Court’s pro-slavery Dred Scott decision and thus had alienated many Southern Democrats.

Even though Bell was a Southerner and a slave owner, his opposition to the pro-slavery proposed Lecompton Constitution of Kansas also made him suspect in the Deep South. Breckenridge, the sitting Vice-President of the United States, was solid on slavery, but he was a committed Jacksonian Democrat and his willingness to be part of an effort to divide the Democratic Party alienated many northern Democrats and conservative former Whigs.

There were, however, presidential candidates in the field in 1860 who might have united the three groups. One was Sam Houston, the governor and former president of Texas, but two even better candidates who actually sought the Democratic presidential nomination in the fall of 1860 were United States Senator R. M. T. Hunter of Virginia and James Guthrie, a former Kentucky legislator, United States Treasury Secretary, and railroad president.

Hunter, who was the official presidential candidate of the Virginia Democrats, was a former Whig who had switched to the Democratic Party in 1844, but had retained close relations with his former colleagues. He had even been offered a cabinet post in the Whig Administration of Millard Fillmore in 1850. He was a staunch supporter of slavery, and he had campaigned in the Senate in 1857 to admit Kansas as a slave state under the Lecompton Constitution.

Even so, Hunter could still have appealed to Northern Democrats and conservative Whigs. He was perceived as a strong unionist and his leading role in the drafting and passage of the Tariff of 1857, which had sharply reduced rates and which was popular among Northern Democrats, also gave him appeal north of the Mason-Dixon Line. His previous service to the Whig Party was likely to appeal to Southerner and Border State veterans of the Whig and American parties.

The second alternative candidate at the Democratic convention in Charleston was Kentucky’s candidate, James Guthrie, who was best known for his having reduced the national debt by almost two thirds while Secretary of the Treasury during the Pierce Administration.

Like Hunter, Guthrie had the potential to appeal to both Democrats and conservative former Whigs. Although a pro-slavery Democrat who campaigned for a Kentucky state constitutional clause that prevented the state from abolishing slavery, he had been a strong supporter of internal improvements while in the Kentucky legislature and had frequently been allied with Whigs on such issues. He also had a history of direct involvement with internal improvement companies—another Whig favorite. He had participated in a number of canal and turnpike companies in Kentucky, and in 1860 he was the president of the Louisville & Nashville Railway, a major southern railroad.

At the Democratic Party’s initial nominating convention in April of 1860, Stephen Douglas was the choice of a majority of the convention’s delegates, even counting the substantial number of pro-slavery delegates who walked out of the convention in protest of Douglas’ policies. However, even though the Convention went through 57 separate ballots in its effort to nominate a candidate, it was clear at the outset that Douglas was not going to receive the 2/3 majority then required for the nomination.

In fact, it was clear as early as the third or fourth ballot that Douglas was not going to receive the necessary number of votes. Had Douglas withdrawn, which he refused to do, the convention would likely have turned to either Hunter or Guthrie, depending on when the withdrawal occurred. Hunter finished second to Douglas on seven of the first eight 8 ballots, but by the tenth ballot, his supporters appear to have begun to move to Guthrie, who was the runner up to Douglas on ballots 10 through 57.

Had the Democrats nominated either Hunter or Guthrie in April of 1860, instead of reconvening in Baltimore two months later and nominating Douglas, it is unlikely that the Southern wing of the party would have broken away and nominated its own candidate. Moreover, it is also likely that the Constitutional Union Party would have supported the Whig-friendly Hunter or Guthrie rather than risk dividing the vote and electing an anti-slavery Republican. A number of members of the party, including Sam Houston, had called for such a strategy but neither Douglas nor Breckenridge were acceptable candidates for many of the party’s supporters.

Of course, if Hunter or Guthrie had been nominated, to have prevailed as a fusion candidate, the candidate would have had to have done better than just capture all of the Douglas, Breckenridge, and Bell votes (since Lincoln would still have won under that scenario.). What else would have had to have happened to prevent a Lincoln victory?

Had there been a single opponent representing the anti-Republican forces, that candidate would clearly have carried the lightly populated western states of Oregon and California, which Lincoln won with pluralities in the 30% range. The fusion candidate would also have received all seven of New Jersey’s electoral votes.

(In actuality, the three non-Republican parties formed a fusion ticket in New Jersey in 1860, as they also did in New York and Pennsylvania, but in New Jersey, electors for all three opposition candidates remained on the ballot, allowing the Republicans to capture 4 of 7 electors, even while taking less than half of the popular vote.)

Even with those three states added to the states carried by the three actual opposition candidates in 1860, Hunter or Guthrie would still have needed to capture 18 additional electoral votes in order to win.

In what states was Lincoln’s majority the slimmest, since those would have been the states most easily moved into the opposition column?

As it turns out, the two states in which Lincoln received the smallest majorities were his home state of Illinois (50.1%) and his former home state of Indiana (51.1%). A shift of only 2,356 votes in Illinois would have transferred its 11 electoral votes to the opposition candidate, while a total of 2,962 shifted votes would have won over the Hoosier state’s 13 votes. Such a shift would have made Hunter or Guthrie the winner by an Electoral College majority of 158 to 145.

Of course, there is no way to know if an R. M. T. Hunter or James Guthrie candidacy would have produced that result. Given the importance of carrying Indiana and Illinois, the Kentuckian Guthrie might have been the stronger candidate. Because of the well-documented affinities between the southernmost portions of Illinois and Indiana and the Blue Grass state (especially in the mid-19th century) a larger number of voters might have turned out for, or switched their votes to, a Kentucky presidential candidate committed to keeping slavery as an American institution south, but not north, of the Ohio River.

Of course, if Hunter or Guthrie had been elected president in 1860, there would have been no Civil War in 1861. At the same time, there presumably would have been no Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and no end to slavery in 1865.

As it turned out, Hunter and Guthrie pursued sharply different paths after the 1860 election. Hunter ultimately supported Virginia’s decision to secede after the firing on Fort Sumter and the calling up of the troops by President Lincoln. In fact, he served as the first Confederate Secretary of State and from 1862 to 1865 as President Pro Tempore of the Confederate Senate where he represented Virginia.

Guthrie, on the other hand, remained loyal to the Union throughout the Civil War, although he never abandoned his support of slavery. Representing Kentucky in the United States Senate during Reconstruction, he opposed both the 13th and 14th Amendments and was a vocal supporter of President Andrew Johnson and an opponent of Radical Reconstruction.

PBS documentary Lincoln@Gettysburg paints a vivid picture of Lincoln and those close to him in the days surrounding his oration at Gettysburg. Lincoln’s wife Mary Todd begged him not to leave for Gettysburg because their young son Tad was seriously ill. He went anyway. Lincoln’s valet, William Johnson, an African-American free man, accompanied Lincoln to Gettysburg and listened to Lincoln practice his speech that morning. Lincoln left Gettysburg with a fever and came down with smallpox. Johnson died weeks later from smallpox after caring for Lincoln. Lincoln chose the inscription “Citizen” on Johnson’s tombstone, and Johnson was buried at Arlington cemetery.

PBS documentary Lincoln@Gettysburg paints a vivid picture of Lincoln and those close to him in the days surrounding his oration at Gettysburg. Lincoln’s wife Mary Todd begged him not to leave for Gettysburg because their young son Tad was seriously ill. He went anyway. Lincoln’s valet, William Johnson, an African-American free man, accompanied Lincoln to Gettysburg and listened to Lincoln practice his speech that morning. Lincoln left Gettysburg with a fever and came down with smallpox. Johnson died weeks later from smallpox after caring for Lincoln. Lincoln chose the inscription “Citizen” on Johnson’s tombstone, and Johnson was buried at Arlington cemetery.