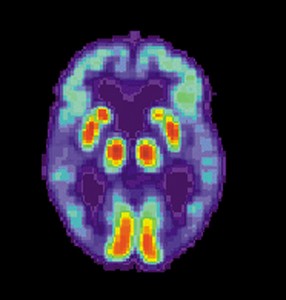

When does life end? The question has important consequences for many areas of law, from criminal law to trusts and estates to taxes. The law has traditionally associated death with a cessation of cardiac and respiratory functioning, but advances in medical technology now mean that hearts and lungs can be kept working artificially for long periods of time. As a result, U.S. law has generally shifted over the past half-century to a new definition of death that turns on whether there has been an irreversible loss of brain functioning. However, as 3L Rachel Delaney explains in a new paper on SSRN, Orthodox Jews have continued to adhere to the old cardiac standard as a matter of religious law. This creates a potential for conflict and the possibility of further emotional harm for family members at a time when they are already dealing with the loss of a loved one — for instance, if a brain-dead patient were withdrawn from life support at a time when the patient was not actually dead according to the family’s deeply held religious beliefs.

When does life end? The question has important consequences for many areas of law, from criminal law to trusts and estates to taxes. The law has traditionally associated death with a cessation of cardiac and respiratory functioning, but advances in medical technology now mean that hearts and lungs can be kept working artificially for long periods of time. As a result, U.S. law has generally shifted over the past half-century to a new definition of death that turns on whether there has been an irreversible loss of brain functioning. However, as 3L Rachel Delaney explains in a new paper on SSRN, Orthodox Jews have continued to adhere to the old cardiac standard as a matter of religious law. This creates a potential for conflict and the possibility of further emotional harm for family members at a time when they are already dealing with the loss of a loved one — for instance, if a brain-dead patient were withdrawn from life support at a time when the patient was not actually dead according to the family’s deeply held religious beliefs.

Rachel thus argues that the law should recognize a religious exception to the brain-death standard. Indeed, she contends that such an exception may be required by the Free Exercise Clause.

Rachel’s article is entitled “Defining Death: Why All Fifty States Should Adopt the Uniform Definition of Death Act with a Religious Exception.” The abstract appears after the jump.

This article addresses the tension between the secular, American definition of death and the Jewish law definition of death. While the definition of death has been debated separately in both Jewish and American legal scholarship, the secular and Jewish law definitions of death have not been thoroughly analyzed in relation to one another. The secular definition of death — irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain — conflicts with the Jewish law definition of death — irreversible cessation of respiration. The conflict presents a First Amendment Free Exercise Clause challenge because state laws with strict secular definitions of death preclude Orthodox Jews from practicing Judaism in their final stages of life. This article argues that each state should adopt a definition of death statute that acknowledges the competing goals at issue in the legal definition of death — the recognition of the personal and private nature of death versus the accomplishment of secular and state objectives. New York State offers such a law by including a religious exception to the secular definition of death. Not only does the religious exception provide comfort to families in sad and serious times, but the exception is required by the First Amendment Free Exercise Clause and the right to privacy, and the exception does not significantly interfere with state interests.

Thank you for a fascinating piece, Rachel. I learned a few new things about Jewish law and this particular bioethical question. If I may offer a few comments. . . .

First, I was surprised that you didn’t mention Glucksberg v. Washington, 521 U.S. 702 (1997), the U.S. Supreme Court decision holding that there was no constitutional right to physician-assisted suicide. Though there may be state cases (those you cited and the recent Montana Supreme Court decision) on point, Glucksberg is the leading federal case and needed mention.

Second, President Bush’s Council on Bioethics did an exhaustive study of the question of when death happens. You can find it online here: http://www.thenewatlantis.com/docLib/20091130_determination_of_death.pdf. I think you’d find it very interesting and helpful.

Third, I think it’s worth noting that it’s possible that Orthodox Judaism is not the only religion to adopt the cardiac standard and reject the brain death standard. There is a general consensus, stemming from comments made by Pope John Paul II, that brain death is morally acceptable in the Catholic tradition. There is, however, a vocal minority of Catholic bioethics scholars who are deeply skeptical of the brain death definition (see http://initiative-kao.de/KAO-Braindeath_is_not_death.htm and http://www.catholicnews.com/data/stories/cns/0804460.htm), particularly as specified in the UDDA. Moreover, a little google searching reveals that this seems like a matter also under argument within Islamic jurisprudence. So perhaps your article’s suggestion of a religious exemption will have broader implications beyond just Orthodox Judaism.

Religion Clause Blog reports today that Islamic scholars are debating this very topic based on the UAE’s recent decision on organ donation.