“The movie “The King’s Speech” is the story of . . . .”

How do I begin to tell you what it is about?

Do I:

give you the history of which King of England is the subject of the movie, or

tell you it is about a speech problem he had and the unique relationship that he and a speech therapist (who had no credentials) developed to mitigate the problem, or

tell you about the likely problems that caused his stammering or the relationship this has to his brother who abdicated the throne to marry Mrs. Simpson?

With mountains of information, visuals, and audio recordings available, how does an author or screen writer:

pick and choose what tells the story best,

order it in an understandable fashion, and

tell the core of the story (in this case, the character and relationship of a King and a commoner and a speech impediment) in a fashion that connects to the viewer?

With mountains of discovery, investigative reports, photos and video available how does a trial attorney:

pick and choose what tells the story best,

order it in an understandable fashion,

and tell the core of the story (in our cases, how the accident or event occurred, the contract breached or employment wrongfully terminated and the damages that were caused and who is responsible) in a fashion that connects to the juror?

Notice how similar the organizational job of a trial lawyer is to that of authors and screen writers. Authors and screen writers have it easier than trial lawyers, though. Trial lawyers have it harder because they have a person looking over one shoulder saying, “I object, that is not true and not proper,” a second person in a black robe looking over the other shoulder saying “yea” or “nay”, and that first person getting to present their own story.

Beyond the recognition that the organizational job of the trial lawyer is much the same as that of the author and screen writer, the second recognition the trial lawyer must achieve is to observe what screenwriters and authors do in how they present and communicate with other human beings, “audiences,” and what we can take from that in presenting to and communicating with audiences of juries and jurors. (Take note that trial lawyers always have to keep in mind the difference between presentation to the single juror and the ultimate group dynamic that is the jury deliberations.)

There is an annual event for screen writers called The Screen Writers Summit. One recent brochure for a conference listed the topics to be covered as:

Deepening Your Story through Theme and Ideas

Making Your Story More Cinematic through Images

7 Steps to a Great Premise

How to Breakdown Scenes

The Essential Conflict all Characters Must Face

8 Steps to a Powerful Pitch

Writing Effective Dialogue

The topics “Deepening Your Story” and “The Essential Conflict All Characters Must Face” are of utmost importance in a trial. If all you are telling is facts, you have just scratched the surface. Jurors want to know what our witnesses (the characters in our stories) are about. They want to compare what they did knowing the background and “story” of the witness. My mantra is “character counts,” not just in life in general but also in trials. That character must be wrapped into a theme that will resonate with the jurors.

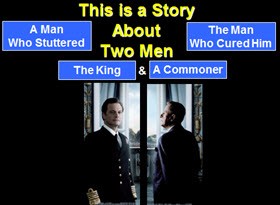

The topic “Making Your Story More Cinematic through Images” underscores how important demonstratives are to a trial story. But do not just think of demonstratives just for the evidence phase of the trial. They are as much or more important in the opening statement. Here is how we might set up “The King’s Speech” if we were telling the story in court:

If I used that slide in opening arguments, it would be a builder slide with the title “This is a Story About Two Men” appearing first. Then “A Man Who Stuttered” would come onto the screen followed by the contrasting “The Man Who Cured Him.” Note how I used “a” for one and “the” for the other. I am not sure that is the right format. It could be reversed, or it could be consistent for each. Take note how I reversed “the” and “a” for the next two builder phrases that appeared on the screen with the corresponding photos of each below them. Am I subtly telling you these men are more equal than their titles would tell? Wording choices are an essential part of our art and craft as trial lawyers, especially when we are at the level of telling good trial stories. The subtleties of even small words like “a” and “the” can send important messages.

That slide is based on a slide used in the opening of a shrimp trawler fire case in North Carolina. The owner/captain of the shrimp trawler was suing the fire department and its chief for how a fire was fought on his ship while docked in a harbor. The trial would be a maze of fire science experts testifying how below deck ship fires should be fought. But one basic inescapable fact was that the fire chief placed himself and his men below deck to fight the fire as part of his decision in choosing how to fight the fire. The case was tried shortly after 9/11, and we made it a character story. Here is the opening slide:

Two topics from the Screenwriter’s Summit, “8 Steps to a Powerful Pitch” & “7 Steps to a Great Premise,” apply to the most important sentence we ever say during a trial: “This is a case about . . . .” That sentence, with only 15 or so words in it, is our “elevator pitch” & premise to the jurors. It is the bumper sticker of our case. It must interest them and give them a memorable phrase to use to construct their story.

The topic “How to Breakdown Scenes” is exactly what we do when we put together a direct or cross. Each of those are a “scene” in our “story” and we have to “screen write” it. We have to consider what the visuals will be and what the linguistics will be. We have to consider how we will use the “stage” of the courtroom, where we will stand and move, and where and when we will have the witness come down off the stand to use a demonstrative or an exhibit.

The last topic from the Screenwriter’s Summit, “Writing Effective Dialogue”, is not the closing and the opening, but the effective writing of “Qs & As”: the dialogues we have with witnesses on direct and cross. We should know what the answers will be from discovery. Our job is more than just soliciting answers, but using the answers in a way that advances not just the legal elements of our case but the story of our case. When a trial lawyer tries cases by telling a story and not just satisfying the legal elements, they are appealing not only to juror intellect but also to juror personal interests. That combination of intellect and interest is the most powerful force you can have to achieve a successful verdict.

CONCLUSION

When you prepare for your next trial, think beyond the facts and elements of the causes of action and think “lights, camera, action”. Think about the power of telling a story and not just telling the facts.

J. Ric Gass is a member in the firm Gass Weber Mullins LLC, in Milwaukee. Ric is a Fellow of the American College of Trial Lawyers, Litigation Counsel of America and the International Society of Barristers and a Diplomat in the American Board of Trial Advocates. He is a Past President of the Federation of Defense & Corporate Counsel, Lawyers For Civil Justice and Litigation Counsel of America. Ric has tried over 300 cases to verdict and represents both defendants and plaintiffs. Ric’s verdict representing a public corporation and a private manufacturing client of $104.5 million is the largest verdict in the State of Wisconsin. This article was previously published in Litigation Counsel of America, 4 Commentary & Rev. 85.

J. Ric Gass is a member in the firm Gass Weber Mullins LLC, in Milwaukee. Ric is a Fellow of the American College of Trial Lawyers, Litigation Counsel of America and the International Society of Barristers and a Diplomat in the American Board of Trial Advocates. He is a Past President of the Federation of Defense & Corporate Counsel, Lawyers For Civil Justice and Litigation Counsel of America. Ric has tried over 300 cases to verdict and represents both defendants and plaintiffs. Ric’s verdict representing a public corporation and a private manufacturing client of $104.5 million is the largest verdict in the State of Wisconsin. This article was previously published in Litigation Counsel of America, 4 Commentary & Rev. 85.