“It requires little knowledge of human nature to anticipate that those who had long been regarded as an inferior and subject race would, when suddenly raised to the rank of citizenship, be looked upon with jealousy and positive dislike, and that state laws might be enacted or enforced to perpetuate the distinctions that had before existed.” – Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 306 (1879)

As ominously foreshadowed by the Supreme Court in 1879, current state and federal laws and practices continuously present disadvantages to people of color. Removed from enslavement and the oppressive nature of the Jim Crow Era, today many of the participants in our justice system and in politics are blind to discrepancies within this nation’s criminal justice system and erroneously believe that the black defendant enjoys the same rights as the white defendant. The black defendant is seldom given a jury that racially represents him or her, and this lack of representation is a product of case precedent, judicial reasoning, and discriminatory practices. In Wisconsin, these discriminatory practices take the form of both state and federal jury pooling procedures. As such, the purpose of this blog post is to draw attention to the disproportionate jury pooling practices in Wisconsin circuit courts as well as federal district courts in our state, and to provide a forum for debate on this important issue.

Federal Jury Pooling in Wisconsin and the Depleted African American Voting Population

The right to a jury is so critical to the makeup of our system of justice that the Constitution mentions juries in four different sections. However, while individuals have a constitutional right to a jury, the pooling and selection of such juries is not always constitutionally executed. Both the Eastern and Western District Courts of Wisconsin have jury pooling practices that raise constitutional concerns due to the disproportional impact that those practices have on black criminal defendants.

In order to guarantee a defendant’s constitutional right to an impartial jury, federal courts in Wisconsin have established a jury selection process wherein a “master jury wheel” is created. The master jury wheel draws citizens from voter records every two years, and then names are randomly drawn to establish a pool of potential jurors. Although this practice seems legitimate, fair, and on its face racially inclusive, it fails to consider the disenfranchisement conundrum.

The disenfranchisement conundrum is as follows: how can a jury pool established by voting records be impartial and racially inclusive when a significant percentage of minorities have been stripped of the right to vote? The right to vote, as alluded to in the Fifteenth Amendment, is not to be denied or abridged. However, under the authority of the Fourteenth Amendment and Richardson v. Ramirez, a majority of the minority population in the United States is stripped of their right to vote. This population of disenfranchised persons, according to a 2016 study, is a rapidly increasing group of 6.1 million Americans.

Felony disenfranchisement refers to the denial of voting rights to an individual or group of people who have committed a crime. Laws surrounding felony disenfranchisement vary by state, some states like Florida, Kentucky, and Mississippi strip all felons of their right to vote while serving their sentence and after completion of their sentence. In contrast, other states such as Vermont and Maine refuse to strip felons of their constitutional right to vote.

Wisconsin felony disenfranchisement laws are not as strict as those seen in Florida and Kentucky, but, nonetheless, still impact the “impartial” jury pool selection process employed by federal courts in Wisconsin. Under Wis. Stat. § 6.03(1)(b), a Wisconsin resident who is convicted of treason, bribery, or a felony automatically loses his or her right to vote. The right to vote, however, can be restored when the convicted felon completes his or her sentence. Sentence, for statutory purposes, includes the successful completion of both imprisonment and any term of probation or extended release.

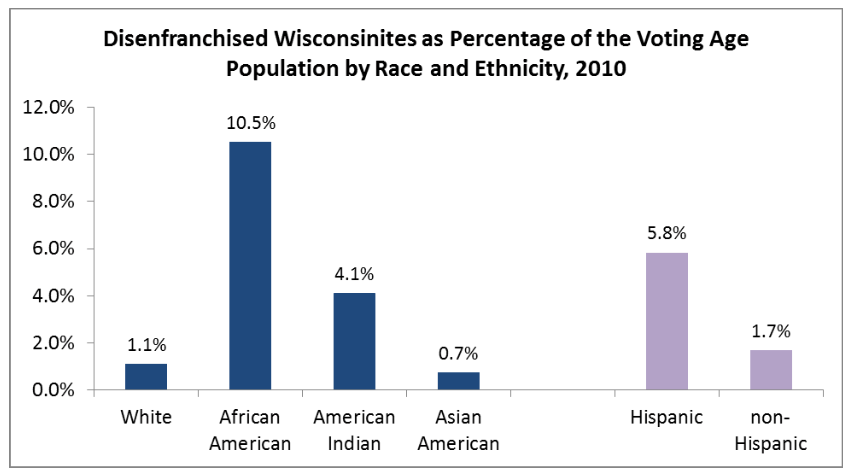

Pulling from data from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections, Bureau of Justice Statistics, the U.S. Bureau of the Census, and the Pew Foundation, a 2012 study out of the University of Minnesota concluded that disenfranchised African Americans made up 10.5 percent of the overall voting-age population in Wisconsin. The black community in Wisconsin already makes up a small percentage of the overall voting-age population, so removing 10.5 percent of eligible voters further depletes the probability that a black individual will be selected for jury by a federal court

In addition to the depleted pool of black voters caused by felony disenfranchisement, the number of black voters, according to a 2016 study composed by researchers at University of Wisconsin-Madison, is further decreased due to confusion over voter ID laws in Wisconsin. This study focused on the 2016 presidential election, which is relevant to federal jury pooling because both the Eastern and Western Districts of Wisconsin will continue to take voting records from the 2016 presidential election in order to generate names for their “master jury wheel.”

In addition to the depleted pool of black voters caused by felony disenfranchisement, the number of black voters, according to a 2016 study composed by researchers at University of Wisconsin-Madison, is further decreased due to confusion over voter ID laws in Wisconsin. This study focused on the 2016 presidential election, which is relevant to federal jury pooling because both the Eastern and Western Districts of Wisconsin will continue to take voting records from the 2016 presidential election in order to generate names for their “master jury wheel.”

In order to vote in Wisconsin, prospective voters are required to present a form of identification at the polling locations at the time of voting. Forms of identification that are acceptable range from Wisconsin issued driver licenses to U.S. issued passports. Pulling data from Milwaukee and Dane counties, it was estimated that “17,000 Wisconsin voters were kept from the polls” due to confusions produced by strict voter ID laws. Out of this percentage only “8.3 percent of white registrants were deterred, compared to 27.5 percent of African Americans.”

It is clear that both felony disenfranchisement and voter ID laws in Wisconsin act to disproportionately impact the black Wisconsin population. When the federal district courts in Wisconsin use voting records to pull the names used to generate jury pools, this practice increases the likelihood that the individuals whose names are pulled are going to be white—directly leading to the increased probability that black defendants will be tried by all white juries.

Wisconsin Circuit Court Jury Pooling and the Unlicensed Minority

In Wisconsin, having a valid drivers license will not only allow you to vote, it will also guarantee you a spot on state circuit courts’ jury pooling lists. Wisconsin circuit courts use Wisconsin Department of Transportation’s list of people with valid motor vehicle licenses in establishing a database for potential jurors. Just like the federal pooling practice, this technique appears on its face to be systematically inclusive. However, pooling from license records generates a racially disproportionate outcome as well.

In 2016, the Wisconsin Department of Transportation reported that there were 4,250,018 licensed drivers in the state of Wisconsin. Out of all licensed drivers, 790,836 of those licenses had expired. Milwaukee and Dane Counties have the highest low-income and minority demographics in the state of Wisconsin, and these two counties also have a large percentage of drivers who have had their licenses either suspended or rendered expired. For example, in Milwaukee County there were 569,415 licensed drivers, out of which 157,796 were considered expired and subsequently invalid for purposes of jury pooling selection. That means 27.7 percent of licensed drivers in Milwaukee County could not be considered for jury duty. Given 69.4 percent of Wisconsin’s African American population resides in Milwaukee County, the 27.7 percent of invalid licenses presents a serious problem for the fair outcome of the circuit court’s pooling practices.

In addition to those who simply cannot afford the costs of a license, African Americans living in Milwaukee County are continuously subjected to having their license privileges suspended or revoked. After studying majority minority neighborhoods in Milwaukee, John Pawasarat, a research professor at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, found that the failure to pay simple tickets can lead to losing licensing privileges for two years. In fact, fifty-six percent of all license suspensions in the state of Wisconsin occur due to the failure to pay municipal violation citations. Additionally, in those same neighborhoods, it was recorded that “two out of three African American men . . . do not have a driver’s license.”

Recognizing the issue plaguing Milwaukee’s community, Jim Gramling, a former Milwaukee County municipal court judge, started the Center for Driver’s License Recovery and Employability. Statistics from the Center for Driver’s License Recovery illustrate that license suspension is not a community wide issue, but rather an issue directly impacting African Americans. From July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017, eighty-four percent of people assisted by the Center were African American, whereas only four percent were white. Clearly, white individuals are not having their licenses revoked or suspended at the same rate as African Americans. Therefore, while pooling from valid driver’s license lists appears to be more inclusive than using voting records, the truth is that this practice is just as racially exclusive.

If you are interested in more on this topic, including the constitutional ramifications of such pooling practices or how implicit bias and societal racism impacts defendants in a courtroom setting feel free to contact me at nmuller@birdsall-law.com or provide a comment below.

Felony disenfranchisement cuts much deeper than the jury pool. It tells a significant number of Americans, the majority of whom are African Americans, that they do not belong to the national political community. The same is true of voter identification requirements that are designed to keep people from voting. Both practices are shameful examples of law being employed to perpetuate the oppression of a subordinate sector of the population.