My name is Claude Kordus, a Marquette lawyer graduate of a time before most of the readers of this piece were born. In fact, only Professor Jim Ghiardi, our outstanding torts professor, maintains a connection to the Law School. I’m looking forward to being the July Alum Blogger.

While I started my career as a corporate lawyer with the Miller Brewing Company, I early on moved into the business world, where my law degree proved to be useful. I spent thirty-five years at Hewitt Associates, helping companies set human resource objectives and design human resource programs, including employee benefits, salary plans, incentive pay systems, stock option and stock ownership schemes, employee communication materials, and human resource policies and practices.

In this and my following blogs, I will focus on one question: What causes people to be successful in their careers? Whether you pursue a legal career or, like me, make the jump into the “business world,” I believe that those who understand and develop their “soft side skills,” not just “technical skills,” will be the most successful.

Clear evidence exists that career success stems as much from people skills as from technical skills.

Researchers at Harvard, the Carnegie Foundation, and Stanford Research Center have all concluded that 85 percent of job success comes from people skills — only 15 percent comes from technical skills and knowledge.[1] This blog is the first in a series of four in which I plan to address how one can excel on the people side. The titles of the four blogs will be:

- The Three Essentials for Effective Communication

- Communication Specifics—Oral, Visual, and Written

- How People Skills Drive Leadership

- The Power of Words

Communication as a People Skill

Effective communication represents one of the most significant elements in what are called the people skills. One-on-one conversation, coaching and mentoring, team leadership, group discussion, public speaking, persuasive writing, visual communication, and nonverbal body language are just some of the many elements that constitute effective human communication. Recently, the Internet has introduced entirely new forms of communication such as tweeting and blogging.

It is a mistake to conclude that communication effectiveness is of interest to businesses alone. Here are some subjects featured in the recent Law Practice periodical of the ABA[2]:

- “Law Firm Marketing Today: Moving Full Speed Ahead”

- “How to Use Social Media to Network and Build Relationships”

- “A Business-Minded Approach to Business Development: Targeting the Superstar Clients”

- “Marketing Resources”

- “Does Your Law Firm Need a Marketing Director?”

- “Essential Guide Unlocks the Secrets of Selling”

- “How to ‘Package’ Yourself in Job Search Documents and Interviews”

More surprising, we find a full-page ad in the same magazine hawking a manual titled: Selling in Your Comfort Zone: Safe and Effective Strategies for Developing New Business.[3]

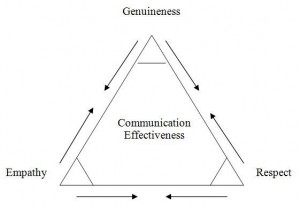

Researchers in the behavioral sciences, as well as communication educators, often suggest three fundamental characteristics that provide a foundation for communication: genuineness, respect, and empathy.[4] For those who are visually oriented, the relationship looks like this:

In efforts to apply these qualities, they appear as a blend, an overlapping; the way we participate in society, in our family, in our social network, and in our workplace, however, all depend on applying these characteristics.

Genuineness is often considered synonymous with transparency. Jack Welch, the storied CEO of General Electric, says that holding a leadership position often becomes a power trip. People in management and executive positions believe that being a boss means exerting control over people and information, that keeping secrets enhances power. In reality, the more successful leader exhibits openness. Transparency is the basis for trust and the key to long-term organizational success.[5]

A genuine or transparent person allows everyone to know what he or she is thinking and feeling. Being genuine provides the avenue for being viewed as a trustworthy person. Interaction, whether as coworkers, manager and subordinate, or otherwise, will be smoother if the persons involved are open.

The need for transparency or authenticity in one-on-one relationships seems fairly obvious. But consider the importance of being genuine in delivering a speech. Studies have shown that people expresse who they are when making a public speech. Words, voice tone and rate, facial expressions, gestures—all send signals that an audience picks up. How often have we listened to a speech and come to the conclusion that the person was genuine or, on the other hand, devious?

Respect is the second key to effective communication; this characteristic may also be labeled caring, acceptance, or people regard. The noted psychotherapist, Karl Menninger, talks of this quality as a person’s “patience, his fairness, his consistency, his rationality, his kindliness, in short—his real love.”[6] Theologians use the word “agape” or “concern for the well-being of others.”[7] Respect stands as a core belief in many cultures and religions[8]:

Christianity: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

Judaism: “What you hate, do not do to anyone.”

Islam: “No one of you is a believer until he loves for his brother what he loves for himself.”

Hinduism: “Do nothing to thy neighbor which thou wouldst not have him do to thee.”

Buddhism: “Hurt not others with that which pains thyself.”

Sikhism: “Treat others as you would be treated yourself.”

Confucianism: “What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others.”

Aristotle: “We should behave to our friends as we wish our friends to behave to us.”

Plato: “May I do to others as I would that they should do unto me.”

Unfortunately, many people in management don’t understand that a positive organizational culture is a climate in which all have respect for the all. This comment is as true for the managing executive of a law firm as for an executive of a corporation. Demonstrating respect, caring for others, sharing kindnesses, and acting humbly will move an organization and a career forward far faster than being focused strictly on efficiency, task correctness, and personal achievement. In the world of work, people who are respectful of others generally receive the same treatment in return. Ralph Waldo Emerson said it well: “The only way to have a friend is to be one.”

There exists much evidence that respect greatly impacts the work world. Fortune conducts a wide-ranging survey of employees at various companies to determine the “100 Best Companies to Work for in America.” Synovus Financial Corporation has often been awarded this designation; it achieved the number one position on the list in 1999. The company’s CEO at the time, James Blanchard, talked about the culture of respect that caused the company to succeed financially as well as humanly in this fashion:

The secret, the clue, the common thread is simply how you treat folks. It’s how you treat your fellow man, and how you treat your team members and how you treat your customers, your regulators, your general public, your audiences, your communities. How you value the worth of an individual, how you bring the human factor into real importance and not just a statement you make in your annual report.[9]

Empathy is the final quality in the triad of essentials for effective communication. Achieving empathy is more difficult than becoming genuine and conveying respect. The first two qualities are behavioral. We can talk about our feelings. We can thank people for extra effort. We can show respect for people through active listening. Empathy, however, involves more heart, more intuition. Empathy is not feeling for someone but feeling with someone. Milton Mayerhoff, in his book Caring, notes: “To care for another person, I must be able to understand him [or her] and his [or her] world as if I were inside it. I must be able to see, as it were, with his [or her] eyes what his [or her] world is like . . . and how he [or she] sees himself [or herself].”[10]

Empathy stems from deep psychological habits, attitudes, and beliefs. We can cognitively work on being more empathetic, but significantly shifting our feelings about ourselves and others is no small task. A friend, mentor, or coach can be useful for this undertaking. For example, ask a friend how you came across when he or she has been talking about a serious personal issue. The listening habits of a person impact greatly on a person’s ability to feel and express empathy.

While the art of empathy is a difficult personal characteristic to improve on, we do get help from one source — our human nature. Neuroscientists have discovered “mirror neurons” that reproduce in our minds the actions of other people. If you watch a person writing on a pad of paper, mirror neurons light up, reproducing the feeling of writing within you. This reproduction provides a foundation for learning. When you watch the action of a top golf pro moving through his swing in slow motion, you are learning how to better swing a club. There is no guarantee you will eventually be a scratch golfer, but it is the basis for improving performance.[11]

These mirror neurons have a lot more to do with our behavior than just helping us recreate the activity of another person; they are also the basis of empathy. When we watch another person, their gestures, facial expressions, tone of voice, word choice, pauses, and other signs of mental activity, we are not just feeling for the person, we’re feeling with the person. For an example of how this occurs, consider a 2008 baseball game between the San Diego Padres and the St. Louis Cardinals. The San Diego pitcher was Chris Young. The St. Louis batter was Albert Pujols. Young wound up, threw the pitch, and Pujols rifled the ball straight at the pitcher’s head. It was too late for Young to move out of the way, and his face was badly damaged. Did Pujols walk off the field and chat with his teammates? No. He sat on his haunches close to the fallen Young as aid was administered. Pujols was distraught, and it was clearly showing on his face.

If we see somebody fall down, we literally fall down with them and rush to their aid. If somebody is crying, we tend to cry. If somebody laughs, we tend to laugh. Being empathetic, then, is so much a part of what it means to be human that it supports much of our person-to–person communication. If we know what the other person is feeling and thinking, how much easier is it to frame our words, our gestures, our expressions to meet the expectations and needs of the other person? This quality of empathy demands our constant attention.

Communication and the Practice of Law

In the practice of law, there are many situations in which communication effectiveness is driven by much more than intellectual content. For example, there is law firm marketing, staff motivation, and internal personal relationships. One of the greatest challenges within any organization is getting all employees to focus on the same goals, the same strategies, and the activities that support these goals and strategies.

Unfortunately, in our culture many people do not effectively use the tools of communication. We read about these tools, but find it difficult to apply them. Our education system, from grade school all the way through college and post-college, spends little time teaching the methods by which we are able to talk and write more effectively with each other.

There are some indications that this is changing. Elite schools, among others, are beginning to recognize the importance of people skills. Garth Saloner, Dean of the Stanford Graduate School of Business, observed in Stanford Business, a magazine for alumni:

[T]he ability to work effectively with and through people is one of the most important determinants of success in any organization. Self-awareness, knowledge of the impact of one’s style on others, and skill at interpersonal interactions are at least as important a part of the leader’s skill set as is training in the more traditional business disciplines.[12]

Saloner also discussed the addition of communication and relationship courses in the curriculum. As we have said, this kind of observation applies equally to the business of law.

I was employed for over thirty years by Hewitt Associates — one of the most successful service firms of the twentieth century and on into the twenty-first. The firm stands as the largest organization in the U.S. providing consulting and administrative services about all aspects of human capital management. Edwin Shields Hewitt founded the firm after World War II and remained its CEO for twenty-five years. He created a culture with characteristics similar to those discussed herein. People cared for each other, people helped each other, and people enjoyed each other. The turnover rate was five percent, the lowest in its industry. Ted Hewitt, as he was known to the associates, placed great emphasis on communication effectiveness, both outward and inward, through mentoring, training, performance evaluation, and simple phatic communication (chit chat). Hewitt grew from less than 100 employees in the 1960’s to approximately 26,000 currently. Hewitt went public in 2002, and the stock price doubled in seven years (approximately a ten percent ROI).

In the next blog in this series, we will investigate some of the most valuable insights into specific communication activities, such as listening, coaching, conversing, group participation, and public speaking. All these specific activities rest on a foundation of the three principles discussed in this article, genuineness, respect, and empathy. In The DNA of Leadership, Judith E. Glaser, a communication expert who has been featured in The New York Times and on the Today show, observes:

Being tough is not being a leader. The leader who leads through personal relationships rather than by positional power creates an environment for open, honest communication where people support and learn from each other. Bringing your humanity to work is essential for twenty-first-century leadership.[13]

Copyright: Claude L. Kordus, 2010. All rights reserved.

[1] Jesse Vickey, Andy Ferguson, and Nicole Vickey, Life After School Explained (Palm Beach Gardens, FL: Cap & Compass, LLC, 2006) 15.

[2] Law Practice, May/June 2010:1.

[3] Law Practice:61.

[4] Robert Bolton, Ph.D., People Sills (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979) 259.

[5] Steven M. R. Covey, The Speed of Trust (New York: Free Press, 2006) 152.

[6] Bolton: 263.

[7] Bolton: 263.

[8] Covey: 145.

[9] Covey: 144.

[10] Bolton: 272.

[11] John B. Arden, Ph.D., Revise Your Brain (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2010) 157-160.

[12] Garth Saloner, Stanford Business, Summer 2010: 5.

[13] Judith E. Glaser, The DNA of Leadership (Avon, MA: Platinum Press, 2006) 98.

Fabulous blog. My nephew is going into his 2nd year at law school and is having doubts about going into law since every lawyer he talks to tells him its not a good career. I keep telling him that you can do anything with a law degree.

This blog proves the point.

Thanks.

Claude, Great blog! Thank you for your insights. Christine

Great work! As a young professional (not in the field of law) I can see how the leaders I admire most have mastered these skills.

Mr. Kordus, this is an EXCELLENT blog! Thank you for succinctly and accurately distilling the key elements of communication needed by all leaders. I am especially interested in locating a source for the research on the 15% technical skills-85% communication skills statistic. I have heard this many times, but have been unsuccessful in locating a source. Can you please help?

Although I am not a lawyer (I was a Professor of Communication and now own a communication consulting firm), I consult with attorneys to prepare their clients to communicate their stories skillfully in depositions and courtroom testimony. While we focus on nonverbal communication in our consulting, all the aspects you mention are involved in persuasive testimony. Thank you for speaking so forcefully in your message. Bravo!

Claude,

I’m a management communication professor. I enjoyed this blog entry and am looking forward to the next one. Yes, tell us more about the research behind the “15% technical skills/85% communication skills” statistic.

Sharon

Hi, Claude … you might (or might not!) remember me from Lincolnshire and Rowayton. How lucky were we that Ted Hewitt put a high value on effective communication.

(By the way, I met Ted in our offices on Wilmot Rd. several weeks before I actually started; I was being oriented and he was in “ex officio” for an Executive Committee meeting. It turned out we had a mutual friend so we chatted off and on during the morning. I left shortly after lunch and learned several days later that he had had either a heart attack or stroke and died soon after I left the building. This was not an auspicious beginning, I feared!)

I VERY much enjoy your writing and I look forward to your next blog.

Cordially,

Barbara

Claude:

I am a 1993 Marquette Law School grad and read your article the other day ( I’m a bit behind in my reading!) I just wanted to say how much I enjoyed it and connected with everything you said! I especially loved the quote at the end. Your insight into communication is wonderful!

Cheryl