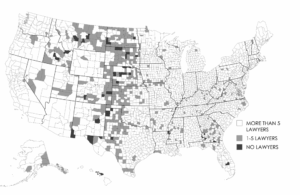

During the past twenty years, the American Bar Association and many state bars have repeatedly proclaimed there to be an acute shortage of lawyers in rural America. A grim picture is painted of “legal deserts”: rural counties beset by a shrinking population of lawyers (in some cases, no lawyers at all) and a widespread reluctance of younger lawyers to forgo the attractions of urban life in order to fill the gap. The argument is that the shortage threatens access to justice and even basic respect for the rule of law in much of the nation.

Counties with Five or Fewer Lawyers, 2020

(generated from a template provided courtesy of mapchart.org)

On such premises, since 2008, nearly half of all states, including Wisconsin, have created rural lawyer recruitment (RLR) programs. These RLR programs variously provide stipends, student loan repayment subsidies, and government legal positions for lawyers willing to commit to rural practice for a set period of time; stipends for students willing to intern with rural lawyers; and support and training for rural practice. Yet to date, most RLR programs have been based on incomplete analysis and ad hoc solutions.

How accurate is the picture of shortage and crisis? The answer is not as clear as many RLR advocates maintain. It is true that, here in Wisconsin, the “Big Three” urban counties (Milwaukee, Dane, and Waukesha) have a lawyer density (number of lawyers per capita) three times greater than do the remaining parts of the state (Greater Wisconsin). But Greater Wisconsin counties vary widely in lawyer density. See the following table:

Rurality and Lawyer Density Trends

| Lawyer density (lawyers per 1,000 population) |

1970 |

2000 |

2010 |

2020 |

|

Big Three counties (average) |

2.27 |

4.67 |

4.87 |

5.35 |

|

Greater Wisconsin (average) |

0.88 |

1.41 |

1.48 |

1.46 |

|

Greater Wisconsin (range) |

0.00-1.56 |

0.48-2.41 |

0.44-2.97 |

0.23-3.78 |

More importantly, even though the disparity existed long before concerns about rural legal deserts arose, lawyer density in the state, on average and proportionally, has changed little over the past half century. Does that mean that Greater Wisconsin—and rural counties elsewhere—have developed dispute resolution systems that don’t need as many lawyers as urban areas? Some research suggests that the answer may be “yes.” It shows that many rural Americans are reluctant to resolve disputes through use of lawyers and the legal system, lest doing so tear at the fabric of community solidarity, tradition, and order—elements much more central to rural, than urban, life.

Still, questions remain. Is there an unarticulated and unfulfilled demand for more legal services in rural areas? If so, how can RLR programs induce more law students and young lawyers to commit to rural practice? These questions have many facets for reformers and scholars to explore. Consider the following:

-

Are there types of legal practice that can be expanded in rural areas? Wisconsin court data indicate that, overall, there is little difference in the types of disputes that make their way to court in rural, mixed, and urban areas. But three types of legal practice show some potential for expansion:

- Immigration law. Burgeoning Latino and Asian populations in rural Wisconsin need help with immigration law matters. To date, few rural lawyers have entered this field.

- Plaintiffs’ personal injury law. Mass advertising by plaintiffs’ personal injury (PPI) firms has led to a significant expansion of business. Some PPI firms specialize in handling and quickly settling low-value personal injury claims that other firms would reject as unprofitable. Their approach is to take on a high volume of claims and settle the substantial majority of them quickly, without much resort to the formal legal process. This model is not universally popular in the bar, but speed and informality are important to rural clients, and there may be a place even for more use of this model in smaller rural communities.

- Alternative dispute resolution (ADR). Many types of ADR eliminate the formality and legal complexities that characterize litigation and transactional law and thus may be a better fit with rural sensibilities, broadly speaking. Can the legal profession persuade rural residents to use ADR more extensively? Can rural lawyers make a living by offering themselves as presiders in ADR proceedings? These tasks would not be easy, but they are worth a serious look.

- Can lawyers make a good living in rural areas? Many RLR programs aver that rural lawyers earn less than their urban counterparts but tout the low cost of rural living as a counterbalance. These points would have to be stated in considerable detail or with great precision to be accurate. Rural lawyer income and expenses vary greatly, with the key to expenses being the size of the lawyer’s family.

- Which lawyers and students are the best candidates for rural practice? Those who talk about the “brain drain” of rural youth to the cities overlook the fact that many of the leavers return home when they become older. There is much evidence that rural practice and rural life are most attractive to rural-raised law students and lawyers. RLR advocates should gear their programs accordingly.

In short: RLR advocates are not wrong to be concerned about the weakening of legal systems in rural areas, particularly in the current age of political polarization and widespread rural alienation. But unless they tailor their programs to better fit rural dispute resolution needs, the intersection of law and rural culture, and the resources available to support such programs, the results achieved by RLR programs are likely to be modest at best.

I look forward to exploring this topic more generally in an article forthcoming this academic year in the Marquette Law Review.

Joseph A. Ranney is the Schoone Fellow for the Study of Wisconsin Law and Legal Institutions and adjunct professor at Marquette Law School.