Recent news reports make much of the fact that, with one exception, none of the current Republican candidates for President has been willing to embrace the theory of evolution as the commonly accepted explanation of how the multiple forms of life currently existing on our planet came to be. Instead, several of the Republican hopefuls have argued pointedly that creationism (the belief that all life was created by God in its current form) is an equally legitimate scientific theory on a par with evolution. For example, Texas Governor Rick Perry has declared that evolution is “just one theory” among several that might explain the current state of biodiversity on the earth. Former Utah Governor Jon Huntsman is the only Republican candidate willing to take a strong position supporting the theory of evolution as a scientifically proven fact.

Recent news reports make much of the fact that, with one exception, none of the current Republican candidates for President has been willing to embrace the theory of evolution as the commonly accepted explanation of how the multiple forms of life currently existing on our planet came to be. Instead, several of the Republican hopefuls have argued pointedly that creationism (the belief that all life was created by God in its current form) is an equally legitimate scientific theory on a par with evolution. For example, Texas Governor Rick Perry has declared that evolution is “just one theory” among several that might explain the current state of biodiversity on the earth. Former Utah Governor Jon Huntsman is the only Republican candidate willing to take a strong position supporting the theory of evolution as a scientifically proven fact.

According to a December, 2010 Gallup Poll, a combined 54% of Americans believe that human beings evolved from less advanced life forms, either under God’s guidance or without any participation from God. Meanwhile, 40% of Americans believe that God created human beings in their present form. The survey results also indicate that the relative percentage of Americans who believe in some form of evolution (as opposed to creationism) rises as education levels rise.

Why then, do the Republican presidential hopefuls almost uniformly reject a scientific theory that is accepted by the majority of Americans? Why express an unnecessary position on an issue unrelated to federal policy that runs counter to the beliefs of sixty percent of voters with a college degree? Most commentators simply assume that any electoral candidate who publicly rejects the scientific evidence in favor of evolution must be pandering to the fundamentalist Christians who comprise the core of the Republican base.

I happen to be Catholic, and therefore my faith does not compel me to reject the theory of evolution. Rather than reading the Book of Genesis literally, the Catholic Church has expressed a lukewarm acceptance of evolution, finding nothing objectionable in the idea that human life developed from lesser life forms so long as God’s role in the evolutionary process is not denied. Nor do many of the “mainline” Protestant faiths, or people of the the Jewish faith, consider the basic tenets of their religion to be challenged by the theory of evolution.

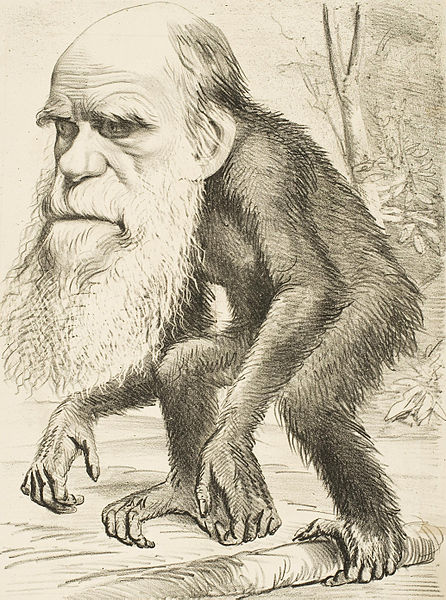

However, those Protestant denominations who self-identify as “fundamentalist” have historically taken a strong stand in opposition to the teaching and/or the endorsement of evolutionary theory by any official government entity. Fundamentalism in the United States began as a reaction to modernist trends in Protestant theology that conceded the human (rather than divine) authorship of the Bible and that therefore interpreted the text as a product of human history and culture. Rejecting the modernist approach, fundamentalists defended the biblical text as both historically and scientifically accurate. While there is a vibrant debate over the extent to which fundamentalism necessarily requires a literal interpretation of the biblical text, those who support the teaching of creationism in our schools strongly oppose any official actions by our secular government that can be construed to deny the legitimacy of a literal reading of Genesis. For these Christians, it is important that the government either refuse to teach evolution as a fact, or else accord creationism an equal weight with evolution in the classroom. The most comprehensive exposition of the divergent religious views towards the theory of evolution, combined with a blow by blow account of the infamous “Scopes Monkey Trial,” can be found in Edward J. Larson’s excellent book Summer of the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion.

Many of these fundamentalist Christians will vote in the Republican primaries. These are the primaries that the eventual Republican candidate will need to win in order to secure the nomination, even if making a public overture in support of creationism risks alienating the moderate and independent voters whose support is needed in order to win the general election. In fact, some commentators have tied Republican skepticism towards evolution to a similar skepticism expressed towards the science supporting climate change. Democratic critics have even alleged that there is a broader Republican “war on science.” Jon Huntsman has warned that the Republican Party risks being perceived as “anti-science” by the electorate.

In today’s political environment, however, I disagree with those who believe that a Republican candidate’s rejection of the theory of evolution will come back to haunt them with independent and moderate voters. In particular, I think that voters who consider themselves to be members of the “Tea Party” movement may actually view a candidate’s skepticism about evolution to be a positive attribute, and that this positive reaction will be a constant among Tea Party supporters without regard to educational level and religious affiliation. It turns out that there is an alternative basis, beyond religious belief or a mere lack of understanding, that explains a hostility towards evolution on the part of some voters. For many likely Republican voters, the theory of evolution has a negative connotation because of the manner in which evolutionary theory was used by progressives early in the twentieth century to justify an “evolving” interpretation of the United States Constitution.

Henry Steele Commager was a longtime Professor of History at Columbia Univeristy and Amherst College. Just as Walter Lippmann helped to define liberal thought in the early decades of the twentieth century, Commager was highly influential in the development of modern liberalism in the middle of the twentieth century. Commager’s 1950 book, The American Mind: An Interpretation of American Thought and Character Since the 1880s, is a tour de force of intellectual history. However, like Lippmann, Commager’s books are rarely read today. In fact, most contemporary readers of both men appear to be political conservatives intent on mining the authors’ criticisms of modern society for insights that can be employed, in jiu jitsu fashion, in order to undermine the authors’ liberal objectives.

Here is how Commager describes the influence of the theory of evolution on the interpretation of the United States Constitution:

Evolution gave a scientific foundation to what some of the wisest of the Fathers had known almost intuitively and to what Marshall and Story had from time to time pronounced, but what scholars had forgotten and what the public, so easily contented with political shibboleths had never fully learned — that the Constitution was not static but dynamic. The historical approach [in opposition to Natural Law] . . . explained much heretofore taken as sacrosanct, as a mere accident, or — if that is too deprecatory — as a product of history. Thus it made clear that the tripartite separation of governmental powers was not something fixed in the cosmic system but a product of two secular considerations: a temporary and perhaps regrettable misconception of the British constitutional system, and a fear of government tyranny. And it suggested that with the passing of these considerations there might well be a readjustment of this mechanical feature of the constitutional system to the realities of politics. It made clear that the profound fear of government which inspired the system of checks and balances . . . was not a reflection of natural law but of conditions peculiar to a time when the moral of history seemed to be that ‘government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence.’ The conclusion was inescapable that the expansion of government activities was not a violation of the moral code — as it was sometimes assumed to be even in the mid-twentieth century — but a logical shift in the use of the Constitution from symbol to instrument, a logical response to the conclusion that government was made for man, not man for government. It made clear that the distribution of powers in the federal system was not a revelation of the divine inspiration of the Framers — as Jefferson Davis thought as late as 1881 when he wrote his Rise and Fall of the Confederate States — but an outgrowth of experience in the British Empire, and it indicated that new experience might justify continuous modifications of that original distribution.

(The American Mind, at 320-321)

The belief in evolution, therefore, threatens more than the theological beliefs of fundamentalist denominations. It can be viewed as a threat to the Natural Law approach of constitutional interpretation and an attempt to unshackle the chains that strict construction of the text place around the federal government.

Commager points to Woodrow Wilson as the key political leader who incorporated evolutionary theory into political science. He quotes Wilson, who wrote, “Living political constitutions must be Darwinian in structure and practice.” Commager sees a clear link between Wilson and the subsequent direction of the Democratic Party in the twentieth century:

And when [Wilson] came to analyze Constitutional Government in the United States he anticipated his even more audacious successor. ‘The Constitution,’ he said, in words that Franklin Roosevelt was to echo, ‘is not a mere lawyer’s document; it is a vehicle of life, and its spirit is always the spirit of the age.’ It ‘was not meant to hold the government back to the time of horses and wagons, the time when postboys carried every communication . . . The United States have clearly from generation to generation been taking on more and more the characteristics of a community; more and more have their economic interests come to seem common interests.’ Notwithstanding his southern inheritance, [Wilson] was ready to acknowledge that a nation had evolved and the Constitution must be read in light of that evolution. As the economy of the nation had become centralized, so must the power of the government to regulate that economy.

(The American Mind, at 324-325)

The Progressive Movement in American history adopted this view of the Constitution and attempted to put it into practice. To a certain extent, they succeeded. However, the growing acceptance of a “living Constitution” among many jurists in the years after Commager wrote inspired an inevitable reaction: the growth of originalism as a competing philosophy of constitutional interpretation. While there are many forms of originalism, in general all “originalists” share the belief that the Constitution should be interpreted through the lens of the original text and intent of the Framers. While originalists concede that accomodations must be made for new technologies, they insist that the original structural boundaries set by the Framers must be maintained unless the text is amended.

The greatest criticism of the evolutionary approach to reading the Constitution, and the strongest argument in favor of originalism, is that by giving the Constitution an evolving meaning liberal jurists were ignoring the question of consent. If it is correct that “the people” are the ultimate sovereigns in our constitutional system, then no alteration in the original design of our government should occur without the consent of the people. While scholars such as Professor Bruce Ackerman have tried to finesse questions of consent in connection with an evolving view of the Constitution, advocates of a “living Constitution” continue to struggle for a convincing answer to this criticism.

In light of the influence that the theory of evolution has had on the dynamic interpretation of the Constitution, it is not surprising that the current crop of Republican candidates feel comfortable publicly expressing skepticism towards the science of evolution. In addition to placating the religious fundamentalists in the Republican base, a critical attitude towards evolution can also be seen as a signal to the advocates of limited government that the candidate stands firmly on the side of originalism in the constitutional debate over the scope of the federal government’s power.

However, while originalism is currently in ascendance as the predominant form of constitutional interpretation, progressives have not conceded the battle to conservatives. In particular, a group of scholars, calling themselves the “new textualists,” have challenged conservative jurists to accord the same respect to the Reconstruction Era and Progressive Era textual amendments as they accord to the original constitutional text. After all, the principle of consent requires that alterations to the text via the amendment process must be respected by the judiciary as an expression of the sovereign will of the people. Consent cuts both ways.

The structural changes intended by the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment should not be evaded through artful grammatical parsing (as practiced, to its discredit, by the United States Supreme Court in a series of nineteenth century precedents). In addition, the Wisconsin state consitutional provisions protecting public access to government (original 1848 text) , preserving the right to vote (added 1986), and providing for the recall of elected officials (created 1926 and amended 1981) should not be interpreted away in contravention of the intent of the voters who approved those provisions. Textual language that was enacted in order to implement progressive conceptions of “good government” is entitled to the same respect as provisions that embody the political philosophy of the Founding Generation. Judges are not free to pick and choose which portions of the constitutional text they will respect.

As long as it can be amended, a constitution can never be completely static. As much as conservatives may wish to ignore the constitutional reforms of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and seek to reconstitute the limited role that government exercised in the colonial era, they are not permitted to do so. Politicians may continue to question whether human beings are descended from lower forms of life, but no one can deny that our constitutions have evolved since 1789.