The Partisan Implications of ‘Low Turnout’ Have Flipped in Wisconsin

There’s a growing conventional wisdom that the two parties have flipped in their relationship to voter turnout. Now, it seems, Democrats are strongest in lower-turnout elections and Republicans do best when turnout is highest.

This is a real paradigm shift from not too long ago. During the Obama years, Democrats enjoyed a clear majority among potential voters broadly defined, but this majority depended on the adults least likely to participate. Republicans, on the other hand, had great strength with the most regular voters. For this reason, Obama could handily win Wisconsin (and the nation) in 2008 and 2012, but the Republican Tea Party wave dominated in 2010.

Here are a few more interesting data points in support of that emerging conventional wisdom.

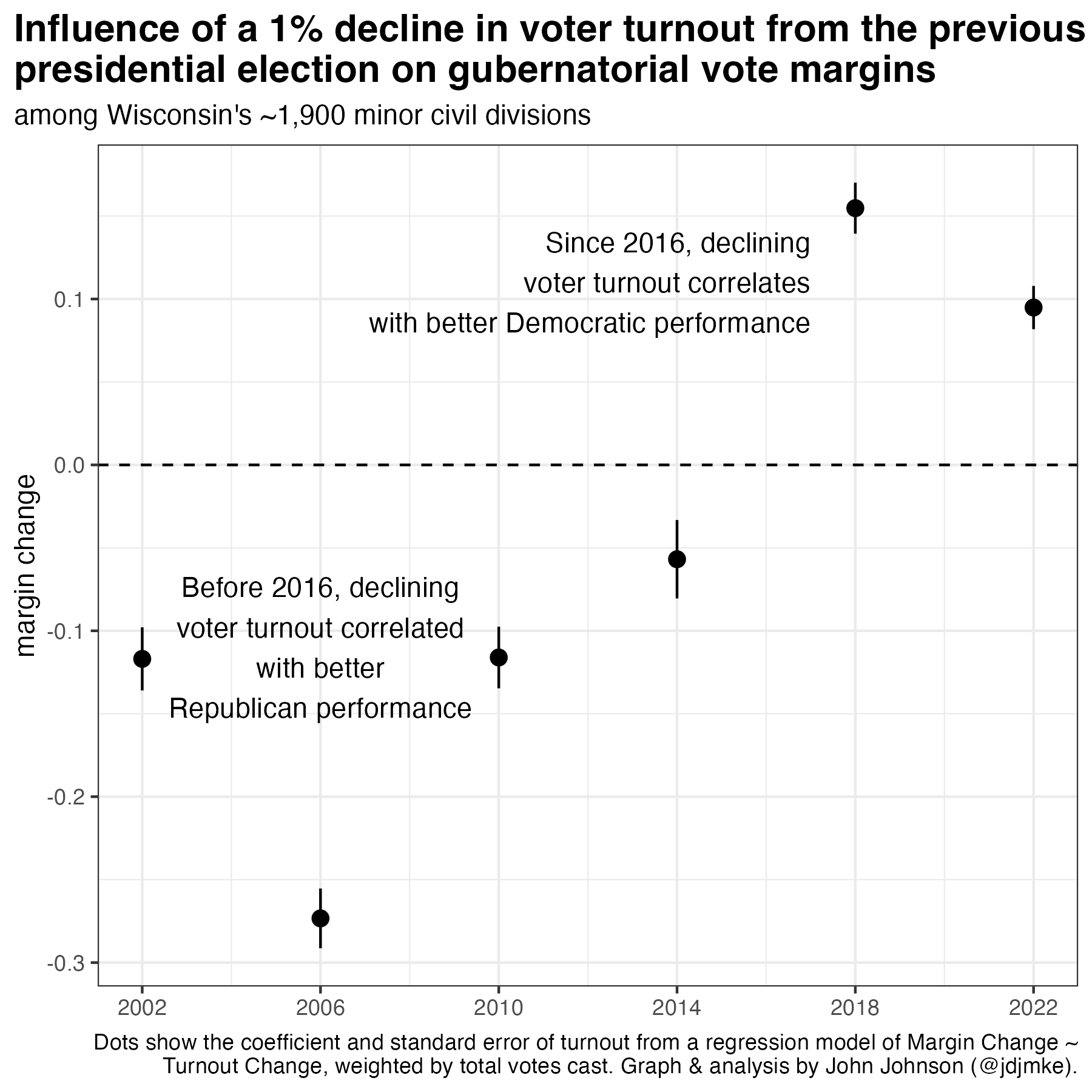

Turnout always drops from a presidential election to the following gubernatorial election two years later, but the size of the decline varies from place to place. I was curious: does the decline in voter turnout correlate with changes in vote margin?

To answer this, I ran a regression comparing each municipality’s change in voter turnout with the change in vote margin between elections for president and governor.

The results are striking. In 2002, 2006, and 2010, a 1% decline in voter turnout from the previous presidential election predicted a more than 0.1 increase in the Republican vote margin for governor. This advantage dwindled in 2014 and reversed in 2018 and 2022.

In both of Tony Evers’ elections, a 1% decline in voter turnout predicted a significant increase in support for Evers, relative to Trump in the same municipality two years earlier.

The same dynamic affects Supreme Court races. The people most likely to show up in an April nonpartisan election are older, highly educated, and more wealthy. These demographics used to lean Republican; now they lean Democratic.

In April 2025, the liberal candidate Susan Crawford won 55% of the vote to conservative Brad Schimel’s 45%. Recall that in November 2024, Trump received 50% of the vote to Harris’ 49% in Wisconsin.

All the evidence I’ve seen shows that Crawford’s improvement over Harris is mostly due to who showed up. A survey from Blueprint Research found that 52% of voters in April 2025 had voted for Harris the previous November, and 46% had voted for Trump. Likewise, the researchers at Split Ticket analyzed ward-level election results and concluded, “roughly 70% of Susan Crawford’s win margin was attributable to changes in who was voting, rather than changes in how people voted.”

Here’s an example of all these trends taken from my hometown, the City of Milwaukee.

This graph shows that in the early 2000s, Democrats did best in presidential elections, a little worse in gubernatorial elections, and much worse in elections for Wisconsin Supreme Court.

In 2002, the Democratic candidate for governor won Milwaukee by 39 points, and in 2004 the Democratic presidential candidate won it by 44. Right in between those two elections, in 2003, the conservative candidate for Wisconsin Supreme Court outright won the City of Milwaukee by 5 points.

Since the early 2000s, things have changed. Democratic presidential margins in the city topped out at 60 points in 2012. Since then, they’ve dwindled slightly. Democratic candidates for governor have just kept climbing. Evers’ margin in 2018 matched Clinton’s share in 2016. But Evers’ Milwaukee margin of victory in 2022 reached heights not even achieved by Barack Obama.

The increase in support for liberal supreme court candidates among Milwaukee voters has been even more spectacular. Liberal candidates were consistently winning the City of Milwaukee by the 2010s, but in 2016, the liberal candidate still trailed Hillary Clinton by 34 points. In 2020, the liberal Court candidate trailed Biden by just 7 points among Milwaukee voters. In 2025, the liberal judicial candidate’s margin of victory exceeded Harris’ 2024 margin by 11 points.

Something fundamental changed in the years following Trump’s first election. Now, the smaller the electorate in Milwaukee, the more liberal it seems to be.