Long-time Brewer fans remember front office executive Jim Baumer as the team’s Director of Scouting and General Manager from 1973 to 1977. Although the Brewers were not successful on the field during Baumer’s time at the helm—Milwaukee finished either last or next to last in the American League Eastern Division from 1973 to 1977—Baumer’s personnel moves laid the groundwork for the Brewer successes of the late 1970’s and the early 1980’s under manager George Bamgardner and General Manager Harry Dalton.

Long-time Brewer fans remember front office executive Jim Baumer as the team’s Director of Scouting and General Manager from 1973 to 1977. Although the Brewers were not successful on the field during Baumer’s time at the helm—Milwaukee finished either last or next to last in the American League Eastern Division from 1973 to 1977—Baumer’s personnel moves laid the groundwork for the Brewer successes of the late 1970’s and the early 1980’s under manager George Bamgardner and General Manager Harry Dalton.

Baumer was the man who signed Robin Yount to his first Brewer contract, and he oversaw the signing and promotion to the majors of Jim Gantner and many other less well-remembered Brewers of that era. As General Manager, he also secured the services of Sal Bando and Cecil Cooper for the team. However, Baumer was not around to enjoy the fruits of his efforts, as he was dismissed by owner Bud Selig after the unsuccessful 1977 season.

Nevertheless, with Baumer’s players filling the roster, the Brewers improved from 69 victories in 1977 to 93 in 1978, as they jumped to third place in the American League East, finishing only six games behind the Yankees and the Red Sox (who ended the 162-game season tied for the best record in Major League Baseball). In 1979, they finished second; dropped to third in 1980; and then had the best overall record in the AL East in 1981 and 1982.

However, today Jim Baumer is best remembered as the answer to two trivia questions: “Who was the scout that signed Robin Yount for the Brewers?” and “Who was the only player to play in the Major Leagues in the 1940’s and 1960’s, but not in the 1950’s?”

The story of how Baumer made it to the Major Leagues with the Chicago White Sox in 1949, but then spent eleven seasons roaming in the wilderness of Minor League Baseball before returning briefly to the Majors in 1961 with the Cincinnati Reds is a fascinating saga of good and bad fortune and one man’s ability to persevere in the face of recurring disappointments.

James Sloan Baumer was born on January 29, 1931, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He grew up in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, a Tulsa suburb, and by the time he was a senior in high school the power hitting shortstop was one of the most highly touted young baseball players in the United States.

Following his 1949 high school graduation he had contract offers from 14 of the 16 Major League teams. (In that pre-draft era, amateur free agents were free to sign with the Major League team of their choice. Unlike the situation in the National Football League, the restrictions of the reserve clause only kicked in after the player signed his first professional contract.)

Baumer eventually opted to sign with the Chicago White Sox for a bonus reported to be $53,000, which at the time was one of the largest signing bonuses in baseball history. (Another recent Oklahoma high school graduate, Mickey Charles Mantle, signed a contract with the Yankees the same month for a bonus of just $1,500.)

The White Sox clearly envisioned Baumer as a potential replacement for aging starting shortstop Luke Appling, who had compiled Hall-of-Fame credentials, but who had just turned 42 years old. The expectation was that the 6’1,” 170 pound Baumer would hit for a high batting average, like Appling, but unlike Appling, he would, as the phonetic pronunciation of his surname implied, also hit for power.

Baumer and his parents travelled to Chicago in early June so that he could sign his “bonus” contract in the White Sox offices at Comiskey Park. His first assignment as a professional ballplayer was to spend two weeks with the White Sox who had just begun a 12-game homestand with a three game set with the New York Yankees.

Baumer was not added to the White Sox’s official roster, but he appeared in uniform at the games and was tutored by Luke Appling during pre-game warmups. When the home series ended, Baumer was to report to the Waterloo White Hawks of the Three-I League. (The three I’s stood for Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa.)

Although Waterloo was a Class B team, which placed it fourth down from the top of the six-level Minor League structure (after AAA, AA, and A, and above C and D), the 1949 White Hawks team contained several of the top prospects in the White Sox organization. (Six of the 1949 Waterloo players would eventually reach the Major Leagues.)

At age 18, Baumer was the youngest player on the team, and he and 19-year old pitcher Richard Duffy were the only teenagers. Most of the White Hawks were between the ages of 20 and 25, and almost all had previous Minor League experience.

Baumer was inserted into the lineup at shortstop as soon as he joined the team on June 14. However, his start at Waterloo was hardly auspicious, as he went hitless in his first 12 at bats. He did homer in his first home game, and his play in the field was uniformly praised. However, offensive woes plagued him throughout the season.

Appearing in 85 games, Baumer batted a disappointing .218 with just 2 home runs. His record, which included a 23 at bat hitless streak in July, was less impressive than that of teammate Herman “Dusty” Rhodes whom he replaced at shortstop. (Rhodes, who moved to second base after Baumer arrived, batted .259 with 4 home runs and was named to the league all-star team.) Infielder Martin Kaelin, who lost his starting position when Baumer arrived and was subsequently demoted to Class C Hot Springs of the Central States League, had been hitting .279 at the time of his demotion.

Waterloo finished in second place in the Three-I League during the regular season, and were then eliminated in the first round of the league play-offs. After the Winter Hawks had closed out their season on Sunday, September 11 (in an extra-inning game in which Baumer went 1-7), Baumer was ordered to report immediately to Washington, D.C. where the White Sox who playing the Senators.

Under the existing Bonus Rules, a player like Baumer who had signed for a bonus above a certain fairly low amount had to be added to the Major League team’s 25-man roster for his second full season or else be placed on waivers where he could be claimed by any other Major League team for $10,000. Since Baumer was going to be joining the White Sox anyway, it probably made sense to add him to the active player list in September when roster limits had expanded to 40 players.

Moreover, it is likely that the White Sox had promised Baumer when he signed his contract that they would bring him back to the Major League club following the conclusion of the Waterloo season. Finally, there was also a chance that curious fans might show up at Comiskey Park to see the 18-year old Oklahoman whose bonus made him one of the highest paid professional athletes in the United States in 1949, even though the team was now more than 30 games behind the first place Yankees.

Baumer debuted with the 6th place White Sox on September 13, 1949. With the White Sox leading the Senators 8-1 in the bottom of the 8th inning, it was announced that Sox starting shortstop Luke Appling was being replaced by rookie Jim Baumer.

Baumer took the field, but before Chicago pitcher Bob Kuzava pitched to Senator outfielder Sam Mele, the next scheduled batter, Baumer was removed from the game. Whether Baumer was injured warming up (as some sources indicate) or whether this was intended to be only a token appearance, he was immediately replaced by Fred Hancock, a weak hitting utility player nearing the end of what would be his only season in the major leagues. Whatever the reason for his removal, under the baseball scoring rules, Baumer was credited with a game played.

His next appearance came a week later in New York, when he pinch ran for pinch hitter Bill Higden, who had walked in the 6th inning of a 10-9 White Sox victory over the Yankees. Baumer reached second base but did not score.

The White Sox returned to Chicago on September 23, for a season ending homestand. Baumer’s first at bat in the Major Leagues came two days later in the first game of a doubleheader with the St. Louis Browns. Once again, Baumer was inserted into the lineup in place of Appling, this time in the 3rd inning. Baumer singled and scored in his first at bat and then played the rest of the game. Although he went hitless in his next two at bats, he did reach base on an error. He also played flawlessly in the field where he initiated two double plays.

His first appearance in the starting lineup came in the second game of the same doubleheader, a 6-2 loss for Chicago. This time Baumer went hitless in two at bats and was pinch hit for by Gus Zernial shortly before the game was called after the sixth inning.

Baumer sat out the next game, but then started at shortstop in four of the White Sox’s final five games. Although his presence had no noticeable effect on the size of the crowd, he actually performed quite effectively in these games, even though he usually split playing time with other young White Sox. In seven plate appearances, Baumer had a single, a double, a triple, two walks, and was twice hit by a pitched ball, giving him for his brief Major League career an overall batting average of .400 (4-10), an on-base percentage of .571 (8-14), and a slugging percentage of .700 (7 TB in 10 AB).

His impressive performance with the White Sox at the end of the 1949 season helped allay concerns arising from his less than stellar performance at Waterloo that summer, and many knowledgeable observers predicted that in the spring Baumer would compete for the starting shortstop position with Appling and Venezuelan rookie Chico Carrasquel, who had been purchased by Chicago from the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Fort Worth farm club shortly after the season ended.

However, the next spring Baumer clearly struggled to keep up with his Major League teammates, and by the end of March his stock had plummeted significantly. The White Sox coaching staff reached the conclusion that his late season performance with the club in 1949 had been a fluke and that he was actually at least three years away from being ready for major league level play.

Baumer’s situation was made even worse by the superb play of Carrasquel, who had been an All-Star at Ft. Worth the year before. Not only did Carrasquel win the starting shortstop job from Appling and Baumer, but he played so well during the 1950 season that he finished third in the AL Rookie-of-the-Year voting and twelfth in the race for the Most Valuable Player in the American League.

To make matters worse, Baumer was also unable to push ahead of established reserve infielders Cass Michaels, Floyd Baker, and the now second-string Luke Appling. By the end of March, sportswriters were beginning to report that the White Sox were having second thoughts about having invested so much money in the untried Baumer.

As required, Baumer began the 1950 season on the White Sox roster, but as of May 11, White Sox manager Jack Onslow had not used Baumer in a single game, even though the team was off to a poor 4-11 start. At that point, Chicago apparently concluded that Baumer had no value whatsoever for the team in the near future and that he needed to be sent back to the minor leagues for more seasoning. To do this, however, the Sox would have to place Baumer on waivers, which could result in losing him to another team.

Of course, if he were claimed by another team, waivers could be withdrawn, but that would require keeping Baumer on the team’s 25-man roster for the rest of the season, which the team did not want to do. In fact, Baumer’s status had declined so much since the previous June that some observers believed that the team would willingly accept the $10,000 waiver price and write off the rest of Baumer’s bonus as a bad investment.

Although it was reported in several newspapers that the lowly Washington Senators planned to claim Baumer off waivers, no claim was forthcoming, so the White Sox were able to option Baumer to the Class A Colorado Springs Sky Sox of the Western League.

Still just 19 and playing in a league one level higher than the Three-I League, Baumer had another disappointing season in 1950. Although his numbers were better in Class A ball than they were in Class B the year before, his record of 22 doubles, 7 triples, and 2 home runs in 120 games with a .259 batting average hardly seemed worthy of a player who had been compared to Rogers Hornsby less than two years earlier. Baumer was technically eligible for the minor league draft in the fall of 1950, which meant that any AA or AAA team could have claimed him, but none did.

The White Sox, however, had not given up on Baumer. Although there was no thought of bringing him back to the Majors any time soon, for the 1951 season, he was promoted to Memphis of the AA Southern Association where his manager was the finally-retired Luke Appling. As the starting shortstop for Chicks at age 20, Baumer had his first reasonably impressive season as a professional. Not only did he play shortstop in 148 of the team’s 154 games, but his .292 batting average, 9 home runs, and .419 slugging percentage also constituted a strong offensive contribution.

At Memphis, he also had the opportunity to play with his older brother, infielder Jack Baumer, and with third baseman Alex Grammas, whom he would hire as the manager of the Milwaukee Brewers 24 years later.

Although his relatively strong performance in 1951 probably guaranteed him at least another year in the White Sox farm system–AAA shortstop Len Ratto was a 30-year old minor league lifer who in 1951 batted only .210 with 1 HR for Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League–the prospect of returning to the Majors still seemed remote. Although Carrasquel’s hitting had fallen off somewhat during his sophomore year, he was still playing superb defense. Moreover, the White Sox had picked up 22-year old shortstop Joe DeMaestri from the Boston Red Sox’s organization to back up Carrasquel.

Consequently, when the White Sox decided that they needed additional starting pitching to improve upon their 4th place finish in 1951, Baumer was viewed as expendable. On October 10, 1951, Chicago traded Baumer and four other players to the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League for hurlers Marv Grissom and Hal Brown. (Seattle was an independent minor league team and the reigning champion of the PCL. Its shortstop, Alex Garbowski, was a weak hitting 29-year old.)

However, before Baumer could play for Seattle, he was drafted into the United States Army in the fall of 1951. Although the Korean War was still in its active phase when Baumer was drafted, the new G.I. never left the United States. Instead, he remained at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma for two years where he played on Army baseball teams. In September 1952, the Baumer-led Ft. Sill team made it to the Fourth Army Championship final game at Ft. Hood, Texas, where it lost to the Brooke Army Medical Center in spite of Baumer’s hitting heroics, and the two matched up again in 1953. In both seasons Baumer was selected to the all-Army baseball team.

At some point in 1952, while Baumer was in the service, the White Sox reacquired his rights from Seattle. After losing Baumer to the service, the Rainiers acquired former Negro League shortstop Artie Wilson from the New York Giants. The 31-year old Wilson had a fantastic 1952 season, batting .316 and leading the Pacific Coast League in hits and eliminating any need for an additional shortstop.

When Baumer returned to organized baseball in 1954, the White Sox, impressed by his performance as an Army baseball player, apparently hoped that he had matured sufficiently while in the service that he might now realize his true potential, so he was invited to the Major League club’s spring training. In fact, in February, he was listed as one of seven players who would be given a shot at earning the starting third base job with the White Sox.

Once again, however, Baumer had a disappointing spring, and he was reassigned to AA Memphis. Unfortunately, his 1954 performance did not match his 1951 effort. He played in only 118 of the teams 154 games, and while his batting average of .279 was respectable, his 4 home runs were hardly what one would have expected from a Major League third baseman.

This poor performance effectively spelled the end of his career in the Chicago organization. Shortly after the 1954 Memphis season ended, Baumer was traded to the Hollywood Stars (the Pittsburgh Pirates AAA affiliate in the Pacific Coast League) along with cash for 32-year old minor league slugger, Jack Phillips.

This trade began what would turn out to be a six-year affiliation for Baumer with Pittsburgh’s AAA teams. However, the new relationship did begin particularly well. With Dick Smith well-established as the Hollywood shortstop, the Pirates decided that Baumer’s best position would be second base. Unfortunately, the 1955 Hollywood Stars roster also included future Hall-of-Fame second baseman Bill Mazeroski, so Baumer actually spent most of 1955 on assignment to the Mexico City Tigres of the AA Mexican League where he appeared to regain his offensive power.

In 1956, he returned to Hollywood where he filled the role of utility infielder, appearing in 101 games while playing all four infield positions. In 1957, he again played all four infield positions, but this time he started over half the Stars games at third base. He also had his best professional season ever at the plate, batting .300 with 14 HR and 76 RBI. Even so, his days as a prospect appeared to be over, and he spent the next three years on Pirate AAA teams in Columbus, Ohio and Salt Lake City, Utah.

After a disappointing 1958 season, Bauman put together back to back strong seasons in1959 and 1960 as the starting second baseman for, and captain of, the Salt Lake City Bees. In 1960, he had a particularly strong season, batting .293 with 14 home runs, and was named the second baseman on the Pacific Coast League all-star team (the first such honor of his professional career).

His solid play at Salt Lake City almost caused the Pirates to bring him up to the Majors in September 1960, when star shortstop Dick Groat went down with an injury. While he ultimately was not recalled, Pittsburgh intended to invite Baumer to spring training in 1961, to compete for a reserve infielder position. However, the team failed to add him to their 40-man post-season roster and left him on the Hollywood roster instead.

As a result of this decision, Pittsburgh ended up losing the rights to Baumer. In November 1960, the Cincinnati Reds, coming off a disappointing 6th place finish, decided to take a chance on the now 30-year old Baumer and selected him from AAA Hollywood in the Rule 5 (minor league) draft.

The acquisition of Baumer was part of the Reds effort to revamp their roster in the 1960-61 off-season. Less than a week after drafting Baumer, the Reds sold their 1960 starting second baseman, Billy Martin, to the Milwaukee Braves, leaving Baumer and 24-year old utility infielder Elio Chacon as the top contenders for the starting job at second base in 1961. In addition to dumping Martin, the Reds also traded away shortstop Roy McMillan, acquired third baseman Gene Freese, a former Hollywood teammate of Baumer, and revamped their pitching staff.

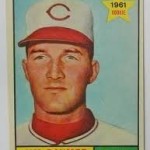

Contrary to his usual pattern, Baumer played extremely well in the spring exhibition season. He not only earned a place on the Reds roster, but he also convinced the Topps Chewing Gum Company to include a Jim Baumer “rookie star” card in its 1961 baseball card set. Although Baumer suffered an arm injury near the end of the exhibition season, he recovered sufficiently to be named to the Reds starting line-up on Opening Day, April 11, 1961. He was penciled into the 8th position in the batting order and at second base in the field.

At this point, the Baumer saga appeared to be taking on the characteristics of a “feel good” Hollywood movie of the 1950’s. In the perfect story, Baumer would excel beyond expectations and lead the unheralded Reds to a championship.

In the real world, the Cincinnati Reds actually did surprise the baseball world and win the National League championship in 1961. However, Jim Baumer had very little to do with the team’s success. When the Reds clinched first place with a 6-3 victory over the Chicago Cubs on September 26, Baumer had been gone from the Red’s roster for more than four and a half months.

In the April 11 game that marked Baumer’s reappearance on the Major League playing fields after an absence of eleven years and seven months, the Reds scored an easy 7-1 victory over the Cubs. Baumer played well in the field in his return, compiling three putouts and two assists while turning a textbook 5-4-3 double play. His contributions at the plate, however, were not as notable, as he went zero for four. He grounded out to end the 2nd inning, struck out in the 4th, reached base on a fielder’s choice in the 5th, and flied out to left in the 8th.

The Reds won two of their next three games with Baumer starting at second base each time. However, his offensive contributions continued to be very limited, as he compiled only two singles (and no walks) in his first twelve at bats. In the three games, he neither scored nor batted in a run. (On the positive side, he struck out only twice.)

Looking for more offense, the Reds substituted Elio Chacon for Baumer at second base for the next three games. Chacon hit only slightly better, and Baumer was reinserted in the line-up when Chacon was injured during the April 19 game. At this point in the season, the Reds were in first place with a 5-2 record, in spite of the lack of offense from their second basemen.

With Chacon still unable to play, Baumer returned to the starting line-up for the next two games. The Reds lost both, and Baumer’s hitting went from bad to worse. In the two games, he struck out five times in five at bats, dropping his batting average to a woeful .118.

For the next game, the Reds moved shortstop Eddie Kasko to second base and started Leo Cardenas at short. Baumer did get into the game as a pinch runner, but the Reds lost again. They lost for the fourth straight time the next day with Kasko again starting at second base.

After two off days, Reds manager Fred Hutchison returned Baumer to the starting lineup. This time Baumer managed a single in four at bats, but he twice stranded runners on base, and the Reds lost 3-2, to fall to 5-7. The next day Baumer started again, but he was lifted for a pinch hitter in the 7th inning after grounding out to end the 2nd and being called out on strikes to end the 4th with the tying runs in scoring position. Again, another loss.

By this point, the Reds had decided that neither Baumer nor Chacon was the answer to the team’s problems at second base, and on April 27 (the day of Baumer’s last appearance for the Reds), Cincinnati traded starting catcher Ed Bailey to the San Francisco Giants for second baseman Don Blasingame and back-up catcher Bob Schmidt.

Blasingame was immediately inserted into the starting lineup, and while Chacon got into one game over the next ten days, Baumer remained on the bench. On May 7, the Reds decided to end the “Jim Baumer experiment” and sent him, along with cash, to the Detroit Tigers for pinch hitter-first baseman Dick Gernert.

In his 27 days as a Red, Baumer had appeared in 10 games, and in 25 plate appearances, he had managed only three singles and a sacrifice bunt. He had neither scored nor driven in a run, and he had struck out nine times. By the time that Baumer’s Topps rookie card reached the market in June, his major league career was over. In his two widely separated stints in the Big Leagues, he had played in 18 games and made 7 hits in 34 at bats for a batting average of .206.

With rookie sensation Jake Wood (who would start 160 games at second that season), Detroit had no need for an additional second baseman, so the Tigers immediately assigned Baumer to their AAA team in the Pacific Coast League, the Denver Bears.

Whether Baumer’s poor performance in April 1961 was related to his spring training injury, or whether it was the product of nervousness or bad luck is hard to say, but once he returned to AAA baseball, he again became a productive offensive player. In fact, his 1961 season with Denver was arguably his best as a professional baseball player. His batting eye returned once he got to Denver, and as the team’s everyday second baseman, he took advantage of the city’s high altitude to hit a career high .310 with 12 HR and 72 RBI.

In spite of his fine season at AAA Denver, Baumer went undrafted after the 1961 season, so he returned to the Mile High City in 1962. Unfortunately, 31-year old second basemen in the Minor Leagues were (and are) clearly expendable, even if they are playing well.

Although Baumer was batting .330 after 40 games for the Bears, the Detroit organization wanted more playing time for 23-year old prospect Legrant Scott (who actually never made it to the majors), so the team traded Baumer to the Atlanta Crackers, the AAA farm team of the St. Louis Cardinals.

With the Crackers, Baumer split his time in platoon situations at 1B and 3B. After batting only .254 with 5 HR in 93 games for Atlanta, and seeing no future for himself in the Cardinals organization, Baumer decided to give up Minor League baseball.

This was not, however, the end of his baseball career. Instead of returning to the Minor Leagues in 1963, he and one of his Denver teammates accepted an offer to play for the Nishitetsu Lions of the Japanese Pacific League, one of the two major leagues of Japan.

Baumer played shortstop and second base for the Nishitetsu (now Seibu) team from 1963 through 1967, and proved to be one of the team’s most popular players, earning All-Star recognition and leading the Lions to the Japanese World Series. During Baumer’s time with Nishitetsu, the usually downtrodden Lions finished in the Pacific League’s first division four times in five seasons, including one championship and two second place finishes.

After five successful seasons in Japan, Baumer retired at the end of the 1967 season. At the time of his retirement, he was 36 years old, and had played seventeen years of professional baseball (plus two years in the Army).

After the end of his playing days, Baumer settled in Southern California. However, he was soon back in baseball as he embarked on a successful second career, first as a scout and later as a baseball executive. After stints as a regular scout for the Astros and the Brewers, he became the Brewers Director of Scouting in 1974. The next year, he was selected by Bud Selig as the Brewers’ General Manager.

After being replaced by Harry Dalton as the Brewer GM, Baumer joined the Philadelphia Phillies organization as a scout. In 1981, he was promoted to Director of Scouting for the Phillies, a position that he held for three years. In 1984, he was named the team’s Vice-President for Player Development. Baumer was widely credited with the development of the Phillies Minor League system in the 1980’s, which was one of the most successful in baseball in that era.

Baumer remained a Phillies Vice-President until June 1988, when a general purge of front office staff required him to return to the ranks of working scouts. He was still employed by the Phillies as an area scout at the time of his death from cancer in 1996.

Hi, thanks for the informative post. I learned a lot about my grandfather’s baseball career from this article. I’m curious as to how you chose to write about him, and what your sources are/were for the details. I’d love to hear from you if you have a minute or two to exchange an email. Thanks, Craig Baumer

It is sometimes reported that Baumer left the game due to fainting, a story that Baumer always refuted. A number of articles from 1961 address the fainting story, including an AP article by Frank Eck that appeared in the Kokomo Tribune on May 30, 1961. In the article, Baumer said he suffered occasional dizzy spells resulting from an inner ear infection.