The Law Professor Who Coached the Marquette Football Team

The Marquette University Law School has long been associated with the world of sports. Although the National Sports Law Institute has represented the connection in recent years, the school’s relationship to the sports industry goes back much further than the 1989 founding of the Institute. Federal Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, later the first Commissioner of Baseball, was a lecturer at the law school shortly after it opened; Carl Zollmann, the first major sports law scholar, was on the Marquette Law faculty from 1922 to 194; and a number of outstanding athletes, including Green Bay Packer end and future U. S. Congressman Lavvy Dilweg and Olympic Gold Medalist (and future congressman) Ralph Metcalf studied at the law school in its early years.

The Marquette University Law School has long been associated with the world of sports. Although the National Sports Law Institute has represented the connection in recent years, the school’s relationship to the sports industry goes back much further than the 1989 founding of the Institute. Federal Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, later the first Commissioner of Baseball, was a lecturer at the law school shortly after it opened; Carl Zollmann, the first major sports law scholar, was on the Marquette Law faculty from 1922 to 194; and a number of outstanding athletes, including Green Bay Packer end and future U. S. Congressman Lavvy Dilweg and Olympic Gold Medalist (and future congressman) Ralph Metcalf studied at the law school in its early years.

However, no one has ever combined the two fields more perfectly than Prof. Ralph I. Heikkenin who, during the 1947-48 academic year, both taught full-time at the law school and coached the Marquette varsity football team, at a time when the team played at the highest level of collegiate competition.

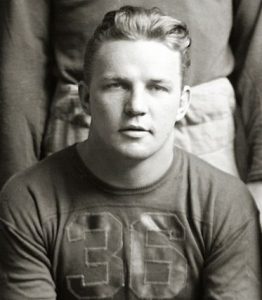

Heikkinen was already well known to sports fans in the upper Midwest when it was announced that he would be joining the Marquette faculty and staff in the spring of 1947. A native of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Heikkinen had grown up in the community of Ramsey. He had enrolled in the University of Michigan in the fall of 1935 where he excelled academically. Not only was he an outstanding student, but he was a published poet and the president of the student government. On top of that, he was an under-sized lineman who made the powerful Michigan football team as a walk on.

Although he began his career as an unheralded newcomer, by the time he was a junior, Heikkinen had developed into one of the best two-way linemen in the country. Although just 6’ tall and weighing only 183 pounds, he was voted as his school’s MVP during both his junior and senior years and was chosen unanimously as a guard on the 1938 All-American team. During Heikkinen’s senior year, the Wolverines, under new coach Fritz Chrisler, narrowly missed a perfect season thanks to a narrow 7-6 defeat at the hands of Minnesota, in which Michigan botched an extra point kick, and a 0-0 tie with Northwestern, which featured a Michigan missed field goal from the 6 yard line. Even so, the team finished the season 6-1-1, ranked #16 in the country in the final Associated Press poll.

After completing his college career, Heikkinen was drafted by the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National Football League. Because of concerns over his size and his interest in playing professional football he was not chosen in the 1939 draft until the 12th round, the #105 overall pick. Since the end of the 1938 college season, Heikkinen had been on the fence on the issue of professional football, and initially appeared to be leaning toward remaining at the University of Michigan as a graduate or law student who would also coach the linemen on the freshmen football team.

Finally, after accepting an invitation to play in the 1939 College All-Star game, which pitted the top senior collegians against the NFL campion Washington Redskins, “Heik,” as he was known, decided to sign with the Dodgers.

However, the football success he had achieved in Ann Arbor was not to be repeated in Brooklyn. Even though NFL players in 1939 were much smaller then than they are today, Heikkinen was undersized by the NFL lineman standards of the time. Also, having missed the pre-season because of his indecision and his participation in the College All-Star game (which was won by Washington, 27-20), he had trouble earning playing time after his arrival in Brooklyn.

Although one of the Dodgers’ 1938 guards had retired and the other had been moved to tackle, Heikkinen lost out in the competition for the two guard positions to two other, less-heralded rookies. After only three games of the 1939 season (in only two of which he actually played) the Dodgers simply released Heikkinen rather than keep him on the bench while paying his salary.

Some published accounts reported that the release had been that Heikkinen’s request so that he could accept a coaching position at the University of Virginia. Whatever the reasons for his release, within three weeks, Heikkinen was in Charlottesville, Virginia. There, he accepted a position as assistant line coach for the school’s football team which has coached by former Marquette head coach Frank Murray. At the same time he enrolled as a first year student at the University of Virginia Law School, even though the fall semester was already underway.

For the next five football seasons, Heikkinen was an assistant coach on the Virginia football team. In 1940, he was promoted to head line coach, a position that he would hold for the next five seasons. Virginia’s football fortunes increased dramatically after Heikkinen’s arrival, but that probably had more to do with the simultaneous appearance of future Hall of Famer halfback “Bullet Bill” Dudley, arguably the greatest player in the school’s history. Although the team’s fortunes fell off after Dudley graduated, in 1944, the team had its second best record since 1925.

When not coaching the Cavaliers, Heikkinen divided his time between his legal studies and his involvement with the University of Virginia’s Flight Preparatory School which was established as part of the United States Navy’s V-12 program during the Second World War. According to the University records, Heikkinen was enrolled as a law student in 1939-40; 1940-41; and 1944-45, although it seems likely that his coaching duties kept him from taking a full load of courses during the fall semester, and he may have taken classes in 1941-42 and 1943-44 to catch up for the work that he had missed.

In 1943 and 1944, he was an instructor in aeriel navigation and physical education for Naval Officers enrolled at UVA under the V-12 program. (The UVA football teams in 1943 and 1944 were greatly strengthened by the presence of the Navy students who were eligible for intercollegiate sports.) It is entirely possible that Heikkinen was also enrolled in the Navy Reserves between 1942 and 1944, in preparation for his service to the V-12 program.

In spite of his protracted time as a law student, Heikkinen excelled academically. When he graduated, he ranked number 1 in his class, and he was selected to Phi Beta Kappa and was one of two law students in 1944 honored with membership in the Order of the Coif. He was also chosen as a member of the University’s prestigious Raven Society. Although his work schedule was not really compatible with law review membership, he did become a member of the staff of the Virginia Law Review during his final semester in law school.

After graduating from law school in June of 1944, Heikkinen remained on Murray’s coaching staff. However, at the conclusion of the 1944 season, he announced his resignation from his coaching position and his decision to accept an associate’s position with the New York law firm of Cravath, Swaine and Moore.

While practicing law in New York, Heikkinen kept his hand in the world of football by serving as a scout for Lou Little’s football program at Columbia University during the 1945 and 1946 seasons.

Following the 1945 season, Coach Murray left the University of Virginia and returned to his previous employer, Marquette University, where he was a legendary figure. As the head football coach of Marquette from 1922 to 1936, the Golden Avalanche/Hilltoppers compiled a won-lost record of 90-32-6, culminating with an appearance in the inaugural Cotton Bowl during Murray’s final game at the helm. Neither of his successors, Paddy Driscoll and Tom Stidham, came close to matching Murray’s success on the playing field, and in 1946, Murray was enthusiastically welcomed back to Marquette.

In 1946, Murray’s first season after his return, the Golden Avalanche went 4-5-0. At the conclusion of the season, head line coach Al Thomas decided to step down. Thomas had actually been Heikkinen’s replacement at the University of Virginia, and he had come back to Marquette with Murray in 1945. As a replacement for Thomas, Murray seized on the idea of convincing Heikkinen to return to the coaching ranks. Heikkinen was initially reluctant to return to coaching, but Marquette was willing to sweeten the pot a good deal by offering Heikkinen a full time position as Associate Professor of Law as well as a job as Murray’s chief assistant with the football team.

Moreover, Murray suffered a heart attack in the spring of 1947, a development that would require his role in the management of the football program to be reduced for the rest of the calendar year. As a result, Heikkinen was offered the chance to run the football team’s spring practice in April and to coach the team from the bench during regular season games in the fall (although Murray would officially remain the head coach). Heikkinen accepted the position in April of 1947, with the stipulation that he would be allowed to retain his New York affiliations and would be free to return to New York at the end of the 1947-48 academic year, if he chose to do so. He arrived in time to oversee the 1947 spring practice.

The law school that Heikkinen joined in 1947 was thriving, as more than 400 students, many of whom were ex-GI’s, streamed into its hallways. (Three years earlier, during the War, the enrollment had fallen to 44 students.) Over the past two years Dean Francis X. Swietlik had quickly rebuilt the law faculty which had been largely dismantled during the war years.

To accommodate the influx of students anxious to return to civilian life and get on with their legal careers, the law school had decided to continue the “three semesters per year” curriculum that it had embraced during World War II. With full length Summer, Fall, and Spring semesters each year, this format meant that law students could graduate from the law school in just two years. Heikkinen’s first class was part of the Summer 1947 semester.

The addition of Heikkinen brought the number of professors on the law faculty to 15, which included eight full-time professors. Four–Dean Francis Swietlik, Francis Darneider, E. Harold Hallows, and Willis Lang —were full professors, while four others–James Ghiardi (who joined the faculty in January 1946, after returning from military service in Europe), Warner Hendrickson, Kenneth Luce, and Heikkinen—were associate professors. Of the eight full-time professors, four—Darneider, Swietlik, Lang, and Ghiardi–were Marquette Law School alums, while the other four had law degrees from Michigan, Chicago, Harvard, and Virginia.

In addition, the faculty included seven part-time lecturers and instructors, and a regent, Rev. Edward McGrath, S.J., a Jesuit who was also a professor of jurisprudence. The most prominent of the part-time faculty was Milwaukee lawyer Carl Rix, who taught Property and who was wrapping up his term as president of the American Bar Association.

Associate Professors Ghiardi and Heikkinen, who were only a year apart in age, were both from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (although from opposite ends) and quickly became great friends, often socializing with their wives and with colleague and fellow-Michiganer Kenneth Luce and his spouse.

As a teacher Heikkinen appears to have been readily accepted by his colleagues. He taught a variety of courses, but he specialized in corporations and security transactions, and during the 1947-48 academic year, he and Luce contributed an article on recent developments in Wisconsin corporation law to the Marquette Law Review. Although he was a football coach, Heikkinen had a surprisingly soft speaking voice. As an AP wire service story noted in November of 1947, he had “such a low-pitched voice that he uses a microphone during classroom hours.”

He was also quite conscientious when it came to making sure that his coaching duties and opportunities did not interfere with his classes. Shortly after he joined the faculty in the summer of 1947, he declined a much coveted invitation to coach the North team in the Upper Peninsula High School All-Star football game because it would have required him to cancel some classes. During several away games during the football season that fall Coach Heik had to follow the team in a later train, and in one case, take an airplane, to avoid having to miss any classes.

Under the joint direction of Murray and Heikkinen, the 1947 Marquette football team got off to a roaring start, defeating South Dakota, St. Louis University and Detroit Mercy in its first three games by a combined score of 101 to 47. The winning streak came to an end, however, in game four when the Hilltoppers lost in Milwaukee to a fellow Jesuit school, the University of San Francisco, 34-13. Trailing 28-0 at half, Marquette was never in the ballgame, and the victory elevated the California school to #20 in the Associated Press rankings.

Marquette may have been over-confident coming into the San Francisco game, given that the team was undefeated, and San Francisco was coming off a home loss to Mississippi State. The next week featured the game that most Marquette fans felt was the most important of the season, the annual match-up with the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

The 1947 game, like all the others in the series, was played at Camp Randall Stadium in Madison, and pitted the 3-1-0 Hilltoppers against the 2-1-1 Badgers. Even though Madison was coming off of a 9-0 upset of #12 Yale the week before, Marquette fans seemed confident that this could be one of the rare years that the Catholic school might win out over the state university.

In spite of optimistic predictions of success, Marquette’s offense simply could not gain any traction, and single touchdowns in the first three quarters put the UW ahead 21-0 before MU finally scored. The Badgers subsequently added two more TD’s to Marquette’s one, for a final score of 35-14.

The suddenly dispirited Hilltoppers proceeded to lose their next three games to Michigan State, Villanova, and Indiana, all of which had winning records in 1947. The team finally rebounded in its last game of the season which required it to travel to Phoenix the weekend before Thanksgiving. There, it defeated the 5-2-0 Arizona Wildcats. Rolling to a 33-7 lead in the third quarter, Marquette coasted to a 39-21 victory to bring its final record to 4-5-0, the same mark it had achieved in 1946. However, the season did at least end on a positive note.

Although many Marquette law students had played on the university football team in the years before World War II, the growing expectation that law students in the post-war era would be college graduates all but eliminated the law school football player. It does not appear that any law students played on the varsity football team during Heikkinen’s year as coach.

Following the end of the football season on November 22, Heikkinen continued to be an active faculty member at the law school, and most members of the law school community assumed that he would remain at Marquette the following year. He participated in the spring football practice in late April of 1948, and several newspapers reported that he would be part of the Marquette coaching staff in 1948. However, in August, the university announced that Heikkinen had resigned both his law school and coaching positions so that he could return to law practice in New York.

According to Heikkinen’s friend Jim Ghiardi in a 2014 interview, no one at Marquette ever knew exactly why Heikkinen decided to leave the law school after only one year on the faculty. He may have been disappointed with Murray’s decision to return to full-time coaching in 1948, which would have diminished his role in the program. He also may have simply missed practicing law; after accepting the coaching position in the spring of 1947, he briefly considered turning down the faculty position in favor of a position with a Milwaukee law firm. Also, by the summer of 1948, Heikkinen’s wife was pregnant with the couple’s third child, and Heikkenen may have decided that he could better support his planned large family—the Heikkinen’s ultimately had six children—on the salary of a Wall Street lawyer than he could on his modest assistant football coach-law professor salary at Marquette.

On the Marquette Law School faculty, Heikkinen was replaced by a young law professor named Leo W. Leary, who left the faculty at the University of Texas to return to his native Wisconsin in the fall of 1948. While he never coached the football team, Leary became a Marquette Law School legend in his own right over the next three decades. If you want to strike up an interesting conversation with any Marquette alum over age 70, just ask him or her what they thought of Leo Leary.

Shortly after his return to law practice in New York, Heikkinen became the executive secretary and attorney for the Studebaker-Packard Corporation, an automobile company that had been a Cravath client. In 1958, he left Studebaker and went to work in the legal department of General Motors, where he remained until his retirement in 1978. At different times in his life Heikkinen apparently battled alcohol problems, and at General Motors he was responsible for initiating and establishing corporation-wide alcohol treatment and education programs. After leaving Marquette, he never again worked as a football coach, but at his induction into the Upper Peninsula Sports Hall of Fame in 1973, he was also identified as a former professional football scout, so his involvement with the sport may have continued after 1948.

Heikkinen died in Michigan in 1990, where he lived in the Detroit suburbs.

Although there have not been very many, Ralph Heikkinen was not the only combination football coach and law professor in American history. Lawyer and Hall of Fame coach Daniel McGugin coached the Vanderbilt football team and taught occasional classes at the Vanderbilt law school during the first three decades of the 20th century. Similarly, Fred Folsom taught part-time at the University of Colorado Law School while coaching the school’s football team from 1908 to 1915. However, unlike McGugin and Folsom, Heikkinen was a full-time law professor, and he managed to hold both positions in the post-World War II era, when both coaching and law teaching were more demanding tasks than they had been forty years earlier.

Since it appears that Heikkinen is the only person to have been a full-time major college football coach and full-time law professor at the same time, it is entirely appropriate that he accomplished this distinction at the Marquette University Law School where the connection between law and sports has long been recognized.

Gordon Hylton is a Professor of Law at the University of Virginia School of Law. Prior to joining the faculty at UVA, Professor Hylton was a longtime member of the Marquette University Law School faculty.