Remembering the 1964 All-Star Game

Last week’s Major League All-Star Game was pretty entertaining, as All-Star games go. The game was reasonably close throughout, and the outcome was never entirely certain until the final out was made. Even though the American League jumped off to a 3-0 lead in the first inning, by the middle of the 4th inning, the game was tied at 3-3. The AL went back up 5-3 in the bottom of the 5th inning, before the offense disappeared on both sides. Neither team scored after that point, and together they combined for only two hits and two walks.

Last week’s Major League All-Star Game was pretty entertaining, as All-Star games go. The game was reasonably close throughout, and the outcome was never entirely certain until the final out was made. Even though the American League jumped off to a 3-0 lead in the first inning, by the middle of the 4th inning, the game was tied at 3-3. The AL went back up 5-3 in the bottom of the 5th inning, before the offense disappeared on both sides. Neither team scored after that point, and together they combined for only two hits and two walks.

The 2014 game also ended a string of somewhat one-sided games. In 2011 and 2012, the NL prevailed by margins of 5-1 and 8-0, while last year the American League shut out a hapless NL squad by a 3-0 margin.

Submerged in the discussion of the game were occasional references to the 1964 All-Star Game of fifty years ago. That game, one of the most exciting All-Star games of all time, was played on July 7, 1964, in recently opened Shea Stadium, the new home of the hapless New York Mets. Shea had opened in April in conjunction with the 1964 New York World’s Fair, which was situated on land immediately adjacent to the park.

In the 1964 game, the lead see-sawed back and forth. The American League went up 1-0 in the first inning, only to fall behind 3-1 as the NL tallied two runs in the 4th and another in the 5th. However, the junior circuit, as the AL was still referred to in that era, came back to tie the score in the 6th inning, and then went ahead 4-3 in the top of the 7th when Los Angeles Angels shortstop Jim Fregrosi (who passed away earlier this year) drove in New York Yankee catcher and reigning American League MVP Elston Howard with a sacrifice fly.

This one-run lead held until the bottom of the 9th inning. As the inning began, Hall of Famer Willie Mays faced Boston Red Sox relief pitcher Dick “the Monster” Radatz, who was pitching his third inning of the game. Radatz had previously been unhittable, retiring all six batters that he had faced, including four by strikeout. Suddenly, however, Radatz could not find the plate, and Mays drew a walk. The Say Hey Kid then stole second and a couple of pitches later came around to score on a bloop single to right by his San Francisco Giant teammate and fellow All-Star game starter Orlando Cepeda.

Actually, Mays would not have scored on Cepeda’s hit, but for first baseman Joe Pepitone’s errant throw to the plate. Mays had already stopped on third base but Pepitone threw home anyway. Unfortunately for the American League, his throw from shallow right field landed short of home plate and bounced over the head of catcher Elston Howard, allowing Mays to scamper home with the tying run, while Cepeda advanced to second base.

With the score now tied, NL Manager Walter Alston inserted fleet-footed Curt Flood into the game as a pinch-runner for Cepeda. Radatz, apparently unshaken by his bad luck, then induced National League third baseman Ken Boyer, who had homered earlier in the game, to pop out to third base for the first out. AL manager Al Lopez then ordered Radatz to intentionally walk catcher Johnny Edwards, an average hitter at best, to set up a possible double play.

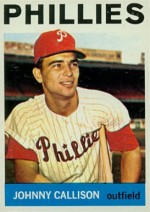

At this point, Manager Alston countered by sending legendary Milwaukee Braves outfielder Hank Aaron up to the plate to pinch-hit for Met second baseman Ron Hunt. Undeterred by Aaron’s reputation as a clutch hitter, Radatz whiffed the legendary outfielder for the second out of the inning. At this point, Radatz had only to retire Philadelphia Phillie outfielder Johnny Callison to send the game into extra innings.

This was Callison’s second at-bat against Radatz, and he alone of the National League batters had managed a solid hit off the 6’6” fireballer, having flied out to deep centerfield for the final out of the 7th inning. Rising to the occasion, Callison did even better in his second appearance.

Wasting no time, he blasted Radatz’ first pitch into the right field stands for a game-winning, three-run home run. Suddenly, a 4-4 tie, seemingly headed for extra innings, had become a 7-4 National League victory.

(Here is a highlight film of the game, which includes Callison’s home run.)

As a reminder of how much baseball has changed since 1964, it is worth noting the All-Star Game of 1964 differed from its 2014 counterpart in a number of ways, beyond having a much more exciting ending.

1. The All-Star Game was a day-time event. In the grand tradition of daylight baseball, before 1967, the All-Star game always began in the early afternoon in the Eastern Time Zone (which meant that it frequently began before noon on the West Coast). Watching the 1964 game, which began on NBC television at 12:45 p.m., presumably required many adults to figure out a way to get the afternoon off from work.

Fortunately, I was an unemployed 12-year old, playing his final year of Little League Baseball, so I didn’t have to worry about free time. In my circles, every boy my age felt obligated not only to watch the game but also to root for one league or the other. For the record, I rooted for the American League.

Night-time All Star Games were introduced in 1967, when the game began at 4:00 p.m. in Anaheim, California, which was 7 p.m. on the East Coast. Since then no afternoon game has been played.

2. The All-Star Game in 1964 was first and last a baseball game. There was very little hoopla surrounding the game other than interest in its final score. Only the starters were introduced by name. Moreover, there was certainly nothing at the 1964 game comparable to the major production made of Derek Jeter’s impending retirement and the minor production around Bud Selig’s announced retirement as commissioner.

No player who participated in the 1964 All-Star game retired after the 1964 season, but it seems certain that if one was planning to retire, he would not have announced it until the end of the season. Commissioner Ford Frick did retire the following year, but he waited until after the 1965 All-Star game to make the announcement. In 1964, a too-early retirement announcement would likely have been denounced as a form of self-aggrandizement.

3. Attending the game in person did not cost an arm and a leg. The most expensive tickets to the 1964 game — those in the box seats — sold for $8.40. If you were willing to sit in the bleachers, you could get in for a buck-twenty ($1.20). According to a Forbes Magazine story published at the end of this past May, the average ticket price for a 2014 All-Star game ticket on the secondary market was slightly more than $1,000, with the cheapest seats going for $367 each.

4. Fewer players made the All-Star team. In 1964, each All-Star team consisted of only 25 players, the number of players on an actual team during the regular season. Although the 25-man roster is still the rule in Major League Baseball, All-Star game rosters have been greatly expanded. This year, there were 34 players on each team. Roster expansion actually began back in 1969, when the number of teams in each league expanded from ten to twelve.

Technically, the expansion in the number of teams, currently 30, has been greater than the expansion in the size of the rosters. In 1964, 10% of current Major League players (50/500) were named to the All-Star game roster; in 2014, the figure was 9% (68/750). In 1964, there was a rule, as there is today, that each team must have at least one representative on the team.

5. Players, not fans, selected the starting line-up for the game. In 1964, the All-Star starters except for the pitcher were selected by a vote of Major League players. In 2014, the starters were selected by a vote of the fans.

Before 1947, the starting line-ups were selected by the All-Star team managers, but in 1947, the selection process was turned over to a fan vote. However, between 1957 and 1970, concern over “ballot-box stuffing” by fans of a particular team, led to the adoption of a system that relied on player voting. Selection of the starting line-ups was returned to the fans in 1970. Since that time “ballot box stuffing” has been encouraged.

Throughout the history of the game, starting pitchers have always been chosen by the All-Star managers. The honor of managing the All-Star team, then as now, went to the manager of each league’s representative in the previous fall’s World Series.

In 1964, that would ordinarily have been Walter Alston of the Los Angeles Dodgers and Ralph Houk of the New York Yankees. However, after the 1963 season, Houk was promoted to General Manager of the Yankees with Yogi Berra named to replace him as field manager. Under the rules, Houk was not eligible to manage in the All-Star Game, and he was replaced, not by his Yankee successor, but by Al Lopez, the manager of the Chicago White Sox, who had finished second to the Yankees in 1963.

6. Many players never got into the game in 1964, and some starters played the entire game. Although substitutions were more frequent in the All-Star game than in a normal regular season game, there was no expectation in 1964 that every player on the All-Star roster would be used in the game. In fact, it was assumed that several of the starters would play the entire game and that many of the reserves would not get into the game, unless it went into extra innings. That a significant number of All-Stars failed to be used by their managers did not seem to generate much controversy in 1964.

In 1964, three National League and four American League starters (including AL catcher Elston Howard), played the entire game. Starters who were taken out usually came out only late in the game. At the end of the 8th inning of the 1964 contest, 10 of 16 starters were still in the game. Altogether only 37 of the 50 roster players appeared in the game, and 5 of the 37 participated only as pinch hitters or pinch runners and another played only one-half inning in the field. In other words, of the 19 position-player substitutes, only 6 played as much as one full inning. Six of the 15 pitchers saw no action at all. Among those who did not get into the game were future Hall of Famers Whitey Ford and Bill Mazeroski .

In contrast, in 2014, 62 of 68 eligible players (32 from the NL and 30 from the AL) made it into the game, and no 2014 position player’s appearance was limited to pinch hitting, pinch running, or a single half-inning in the field. Moreover, every starter had been removed from the game by the end of the 6th inning. (Technically, AL DH Giancarlo Stanton was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the 8th inning, but that was only because a DH can only be removed by being pinch hit for. Stanton last appeared in the game in the 6th inning.)

Curiously, in 2014, for the third year in a row, no San Diego Padre player appeared in the All-Star game although there was, of course, a Padres player on the National League roster each year.

7. In 1964, almost all All-Star pitchers were starting pitchers, and pitchers were expected to pitch up to the three inning maximum unless it was necessary to pinch hit for them. In 1964, American League manager Al Lopez of the White Sox chose only eight pitchers for his 25 man squad, and NL manager Walter Alston of the Dodgers chose only seven. This clearly indicated an expectation that several pitchers would hurl more than one inning. Then as now, pitchers were limited to pitching three innings, unless the game went into extra innings.

Fourteen of the 15 pitchers chosen in 1964 were starting pitchers. The one exception was Boston Red Sox reliever Dick Radatz, mentioned above, who had compiled a truly phenomenal record in relief. From 1962 to 1964, Radatz, while pitching for Red Sox teams that never finished higher than 7th place in the standings, managed to win 40 games and save 78 while striking out 487 batters in 414 innings, all in relief. In contrast, the pitching staffs of both leagues in 2014 were intentionally composed of starters, middle relievers, and closers.

Of the nine pitchers who appeared in the 1964 All-Star game, only one, Philadelphia’s Chris Short, was removed from the game simply so that someone else could pitch. (Short also gave up three hits and two runs in the only inning in which he appeared.) Both starting pitchers, Don Drysdale and Dean Chance, pitched the maximum of three innings, while two others, Juan Marichal and Dick Radatz, were still in the game when it ended. The other four pitchers who appeared were all removed from the game for pinch-hitters. Even though Radatz was a terrible hitter — his lifetime batting average at the start of the 1964 season was .083 — he was allowed to bat in the eighth inning so that he could stay in the game and pitch a third inning.

In contrast, 21 pitchers appeared in the 2014 game. No one pitched more than one inning, and eight pitched less than a full inning. Of course, with the use of the designated hitter in the modern game, the issue of whether or not to remove a pitcher never arises. Nor is the three-inning limitation apparently of any consequence.

8. The two All-Star teams placed a greater emphasis on winning the game in 1964 than they do in the modern era. Judging by the way in which the two managers operated in 1964, this seems to be a valid conclusion. However, at the time, it was a common complaint that while the National League went all out to win each All-Star game, the American League seemed to view the event more as an exhibition game designed to showcase the sport’s stars. The fact that the American League managed only one win and one tie in the 13 All-Star games played between 1960 and 1969 seemed to lend some support to this theory. (There were 13 games in the decade because two All-Star games were played in 1960, 1961, and 1962.)

As mentioned, the way in which both managers handled their rosters in 1964, especially compared to their 2014 counterparts, does suggest that winning meant more to the managers fifty years ago, if not to the players, than it does now. Although Major League Baseball introduced the “league that wins the All-Star Game gets home field advantage in the World Series” feature in 2003, to try to make the All-Star Game appear more significant, getting as many players as possible into the game still seems to be the primary objective of both managers.

9. Fifty years ago All-Star Games didn’t last as long as they do now. Presumably because they featured fewer substitutions and fewer pitching changes, the All-Star Games of the 1960’s were shorter than those of today. Even with a full 9th inning and more scoring the 1964 game lasted only 2:37, compared to the 3:13 for the 2014 event.

There is a simple way to end the hypocrisy that is modern college sport and at the same time preserve the much-beloved pageantry of men’s college football and basketball.

There is a simple way to end the hypocrisy that is modern college sport and at the same time preserve the much-beloved pageantry of men’s college football and basketball.