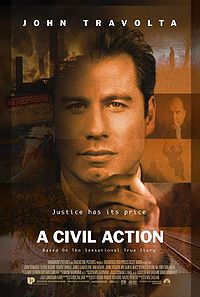

There are many great law-related movies, but the one that has special resonance for me is A Civil Action (1997). In fact, back when I taught Civil Procedure, I required students to watch the film, and we had some really terrific class discussions about it. The plot centers on a lawsuit brought by a group of residents of Woburn, Massachusetts, against several industrial polluters. At the heart of the film is the confrontation between an up-and-coming plaintiffs’ lawyer played by John Travolta and a grizzled, big-firm defense lawyer played by Robert Duvall. The Duvall character seems an avatar of the amoral corporate lawyer, whereas the moral status of the Travolta character seems more uncertain and may evolve over the course of the movie.

There are many great law-related movies, but the one that has special resonance for me is A Civil Action (1997). In fact, back when I taught Civil Procedure, I required students to watch the film, and we had some really terrific class discussions about it. The plot centers on a lawsuit brought by a group of residents of Woburn, Massachusetts, against several industrial polluters. At the heart of the film is the confrontation between an up-and-coming plaintiffs’ lawyer played by John Travolta and a grizzled, big-firm defense lawyer played by Robert Duvall. The Duvall character seems an avatar of the amoral corporate lawyer, whereas the moral status of the Travolta character seems more uncertain and may evolve over the course of the movie.

Both actors deliver deeply engaging performances, as do several other top-flight character actors in supporting roles. (James Gandolfini is especially good as a blue-collar employee of one of the defendants who must decide whether or not to cooperate with the plaintiffs’ lawyer; he doesn’t have many lines, but he exudes this barely subdued rage, looking as if he would like nothing more than to punch somebody out, if only he could decide at whom he should really be angry.)

But, in addition to great acting and a compelling story, there are lots of other reasons this movie really works for me.

For one thing, environmental litigation is what I myself was doing as a lawyer in 1997 (when the movie came out), and who can resist a glamorized, Hollywood version of one’s own life? (Perhaps this also helps to account for the enduring fascination with The Paper Chase among law students and law professors.) Yet, though glamorized in some respects, the depiction of complex environmental litigation in A Civil Action is accurate enough that I consistently found it to be a good way to begin a discussion with students about important problems in the American civil litigation system (e.g., lawyer-client conflicts of interest, plaintiff-defendant resource imbalances, and excessive cost).

Ultimately, though, what I like most about the movie is its dramatization of the profound gap between what the lawyers and court system are willing and able to provide and what the victims of great human tragedy most desperately want. At first, we see the Woburn victims — families who lost children to cancer — only through Travolta’s eyes. The negative stereotype is that plaintiffs’ lawyers see victims only as a meal ticket. For the Travolta character, though, I think he sees his clients less from the standpoint of a financial payoff, and more as a way to get the ego-gratification that comes from playing David to a corporate Goliath.

In any event, the plaintiffs’ lawyer seems to have no empathy for the terrible grief of his clients; indeed, he expressly disclaims any such emotional response by a lawyer as counterproductive to the clients’ legal interests — which he equates with maximizing financial gain. Gradually, we, the audience, come to see that the clients are less interested in money than in an explanation of why they lost their loved ones, an apology for wrongdoing, and generally having their basic human digintity recognized by the big corporate and legal actors in the case. The Travolta character finally seems to get some sense of this by the end of the movie — although there is enough emotional subtlety in the production that we do not get an overly obvious epiphany. Still, I think the movie works as a healthy reminder for lawyers and law students of the human needs for healing and respectful treatment that lie behind much litigation, and that cannot be met through dollars and cents alone.

This movie, as I am sure most of the ones that are picked will be, is also an excellent book. I read it before I started law school and look forward to reading it again soon with a new perspective. It is accessible for those without legal training and provides a sobering picture for those entering the profession with wide eyes. I highly recommend it.

One of the sad realities when addressing law in movies is the narrow perspective of the analysts. Invariably, law is seen within only the American experience despite the inexorable push to broaden law school courses to include comparative legal materials. Even the very recent law review and bar journal discussions about law in film rarely consider foreign films. Yet, many of these authors have been exposed to films such as Rashomon and the Story of Qiu Ju. For whatever reason even the comparativists rarely use cross cultural insights to examine law through the prism of foreign versus American perspectives of law. Because it is commonly acknowledged that we are in a transnational (if not international) age it is essential that law students, faculty and practitioners begin to see the how people outside the United States perceive their own legal systems. Ultimately, the films most likely to provide the deepest exposure to foreign perceptions of law are local favorites rarely available outside of a country’s borders much less in translation (e.g. some of the Tora-san series from Japan).

I have used some of these films in my comparative law course for many years. I have found that students viewing them in concert with supplementary law reviews discussing the specific legal system and culture based written materials make for lively discussions and significant insights into international legal planning.

I respectfully dissent on the movie, which I was underwhelmed by. However, like Jason, I heartily recommend the book. I found it fascinating and gripping. From early on, you can sense Schlichtmann getting lured in over his head, like a gambler following good money after bad, enticed by the unlikely prospect of a big payday. And for future lawyers, the disastrous deposition scene and its aftermath (omitted from the movie, if memory serves) make for a compelling cautionary tale: always expect your opponents will break the rules, and have some sort of plan if they do (or at least don’t throw an expletive-laden fit on the record).

I’m with Mr. Boyden – “Civil Action” was a great book, an underwhelming film. Try “In the Name of the Father” for a better film based on a true-life legal situation (albeit one in another country).

Hmm. Actually at the time I wrote my comment it said “whelmed,” but apparently whelming is experiencing deflationary pressures right now.

I’m with those who like the lawyer portrayals in A Civil Action. The portrayals have aa range and complexity to them, and that’s rare in pop culture.

The film can also be placed in a sizable group of contemporary law-related films in which corporations and big business are portrayed as evil wrong-doers. Off the top of my head, I’d cite The Verdict, Silkwood, Class Action, The Rainmaker, and Erin Brockovich. One could say this shows the populist strain of American pop culture, but there is a sweeter irony to it all. Namely, the culture industry, itself one of our biggest businesses, sells negative images of big business. Everything is indeed for sale in late capitalism.