Michael Ariens has, through a number of blog posts, shared with us his thoughtful sentiments about American legal education. This post is an attempt to continue that dialogue and to consider how we can better prepare our students for practice by contextualizing legal education.

Michael Ariens has, through a number of blog posts, shared with us his thoughtful sentiments about American legal education. This post is an attempt to continue that dialogue and to consider how we can better prepare our students for practice by contextualizing legal education.

Most legal commentators believe the primary purpose of law school is to prepare students for practice. While there isn’t a single interpretation of what that means, it must at least include the ability to help clients “solve” their legal problems. (I use quotation marks around the word “solve” because legal problems are not like most mathematical problems in which there is only one solution.)

While that objective might seem obvious to some, especially the legal practitioner, it isn’t necessarily obvious to everyone, especially in light of the pedagogical approach to legal education that most law schools take. This is because most law school courses teach substantive law, as well as fundamental legal skills like legal reasoning, through the vehicle of the case method.

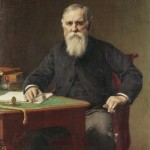

The use of the case method as we know it can be traced to at least as early as 1870, when Christopher Columbus Langdell first instituted it at Harvard Law School in an effort to make the study of law more rigorous. The idea was to treat the law as a science, and to treat cases (the source of the law) as if they were to be poked at and dissected in order to reveal their legal principles. By requiring students to learn the law through such demanding exercises, the case method achieved its goal – law school became a more rigorous enterprise.

Gradually, the case-method became the primary tool used to educate new lawyers. As we lawyers know, the case-method refers to the study of cases – most often appellate cases – where the focus of the inquiry is on the judge’s derivation of a particular legal principle. This approach has translated into casebooks filled largely with portions of appellate court opinions that demonstrate the courts’ legal reasoning rather than any substantial presentation of the underlying facts of the cases.

As a result, casebooks typically fail to provide students with the opportunity to see or understand the context for the litigation, such as the relationship of the parties, the real reason the plaintiff brought the lawsuit, the parties’ strategies in pursing and defending against the lawsuit, or the role of the lawyer in advising her client. Instead, the student sees the case in much the same way that the appellate judge or law clerk might see the case – as a question of law largely removed from the factual context.

In my view, this pedagogy creates a mismatch between the one necessary objective of law schools (to prepare students to help their clients solve their legal problems) and the case method approach that we use in order to train our students (teaching a form of analysis that is devoid of context).

Responding to this mismatch seems to be at the heart of the recommendations of the 2007 Carnegie Report. According to the Carnegie Report, the critical question for legal educators should be how to better combine conceptual knowledge of the law with the experience of practice (and with professional identity).

Many law schools have responded to this recommendation by increasing (or, in some instances, not reducing) the number of upper level practical skills courses that they offer. Even before the release of the Carnegie Report, Marquette University Law School offered numerous workshops providing practical skills instruction. These types of practical skills course continue to abound at Marquette, as do our internship opportunities. Close to 70% of the students in Marquette University Law School’s 2009 graduating class participated in at least one internship.

While practical skills-based courses, as well as internships and clinics, might provide the best environment for students to put their substantive knowledge, practical skills and professional identities to the test, these optional courses should also reinforce what other courses have been teaching our students all along: legal doctrine can only be fully understood when considered in the context in which it is applied. Therefore, I believe that it is important to introduce students to the context in which the law is applied even in (or especially in) their doctrinal courses, including first year courses, because doctrinal courses shape how students think about the law, starting from the first day of class.

I do not propose to discuss here how to accomplish this goal, for I believe that the development of concrete recommendations should only follow a dialogue about how, conceptually, our law school can improve the academic enterprise for the benefit of both our students and the legal profession.

“(I use quotation marks around the word ‘solve’ because legal problems are not like most mathematical problems in which there is only one solution.)”

Is that how law students now tend to think about solving legal problems?

“In my view, this pedagogy creates a mismatch between the one necessary objective of law schools (to prepare students to help their clients solve their legal problems)”

I’ve had 2 extremely bad experiences with lawyers, and had they helped me to solve my legal problem, it would’ve been more of a partnership formed, than a dictatorship created.

Even though clients haven’t been to law school (usually) . . . they’re not dumb and usually know the issue more thoroughly than their attorney.

I happen right now to be reading from the PILS auction booklet (which will be held at the ICC on February 12) a quote from the late Dean Eisenberg that is worth bringing up here: