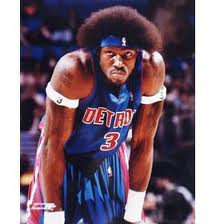

Hey, law students and profs, it’s time for you to fear the ‘fro. Pistons center Ben Wallace reportedly plans to attend law school after he retires from the NBA. At Above the Law, Elie Mystal comments on Wallace’s prospects as a law student, comparing his advantages and disadvantages relative to his classmates. For instance:

Hey, law students and profs, it’s time for you to fear the ‘fro. Pistons center Ben Wallace reportedly plans to attend law school after he retires from the NBA. At Above the Law, Elie Mystal comments on Wallace’s prospects as a law student, comparing his advantages and disadvantages relative to his classmates. For instance:

GRADES: Would you give Ben Wallace a C? I wouldn’t give Ben Wallace a C. What possible good could come from giving Ben Wallace a C? EDGE: Ben Wallace

Amen to that! By the way, given the strength of our sports law program, I hope Wallace will be giving Marquette a serious look. And, as a defensive specialist, he shouldn’t mind too much that our local NBA franchise can’t seem to find the hoop.

Mystal’s post imagines Wallace heading to a lucrative big-firm job, which does point to the more serious issue addressed by my next post: the ease with which wealth can be used to generate more wealth, producing an inequality spiral in society.

As the gap between rich and poor grows in the U.S., I find it fascinating that no serious political movement has emerged advocating a real redistribution of wealth in this country. Yes, Democrats favor some policies that have (or would have) redistributionist consequences, but I don’t hear anyone anywhere near the political mainstream in either party advocating for direct, large-scale wealth redistribution, e.g., by restoring the top marginal income tax rates to what they were a generation or two ago. Why is that?

Seeking to provide some answers to the question, Frank Pasquale has a fascinating post at Balkinization on the politics of inequality. I found this passage especially intriguing:

Everyday experience also helps explain the trend. In Griftopia, Matt Taibbi interviews members of the US Tea Party. He reports that their views of government arise out of their interactions with officials at the IRS, DMV, TSA, zoning boards, or similar agencies: stressful, one-shot interactions with bored, inattentive, or hostile bureaucrats. They project that experience onto places like the SEC, CFTC, FCC, or Fed—assuming that the world of DC agencies is just as exasperating for the multinational corporations regulated by these agencies as local government is for them. They have little sense of the revolving door of high bureaucracy, where the regulators are often on the lookout for jobs at regulated entities. An IRS auditor has no prospect of one day working for a middle class auditee, but MMS staffers have often been smitten with the companies they inspect. (As one report puts it, “The cozy ties included workers who moved between industry and government jobs ‘with ease’— friends who’ve ‘often known each other since childhood.'”)

So a Tea Partier exasperated by DMV incompetence may vote for a party committed to making the MMS inspectors even poorer and more reliant on an eventual big payday at a company they regulate. Lower government wages will likely provoke the TSA/DMV/IRS crowd to be ever surlier to the public, while making the SEC/CFTC/FCC crowd ever more dependent on a big private sector payday. And so the cycle continues.

Pasquale identifies the implementation of the Dodd-Frank bill as a current example of how existing political dynamics diminish the extent to which regulatory initiatives are capable of restraining the inequality spiral:

[A]s Farrell notes, “There are many very influential organizations pushing the interests of business and of the rich . . . . [and] they typically trump voters (who lack information, are myopic, are not focused on the long term) in shaping policy decisions.” Already the implementation of Dodd-Frank appears to be going in this direction, as “3,659 lobbyists worked for companies that explicitly lobbied on the Dodd-Frank bill” in the first nine months of 2010. Over half of voters are unaware that the Republicans just won the House of Representatives; it’s hard to imagine them pressing either party for, say, better derivatives regulation.

Staying on the subject of Dodd-Frank, Jeff Schwartz has some interesting commentary at The Conglomerate on the regulation of hedge funds under the new law. He is skeptical that registration requirements will actually do much to rein in hedge funds:

The idea that registration could help protect investors from fraud is reasonable. It might deter fraud or make it easier to detect. But the Madoff scandal gives reason for pause. Madoff was registered as an investment adviser and his operations had raised red flags with the SEC. Yet the agency failed to uncover the far-reaching misconduct. What this shows is that registration alone is insufficient, and perhaps secondary. More importantly, the SEC needs to right the ship in terms of enforcement. If this happens, then perhaps the rule will prove to be a useful investor-protection tool. While the Act does beef up the SEC’s powers in this regard, my intuition is that the problem is cultural rather than regulatory.

He concludes:

Rather than clearly reflecting any specific normative goal, perhaps hedge-fund registration is a populist response to the unease caused by the vast accumulation of capital in secretive, profitable, and risky endeavors.

Although there may indeed be some lingering feelings of fear and resentment towards wealthy private entities, Pasquale’s analysis suggests why populist fear and resentment of government agencies may be even greater.

I don’t see any time in the future on wealth distribution in this country. You have to look at how Washington works. Regardless of the party in control you have a swarm of lobbyist. If you have the money you can hire a firm of them and get just about anything passed or any form of tax credit for your business arena. Were the little person has no one knocking on the doors of the house or senate daily in their behalf. It is quite simple and we now are in the hands of those who control the wealth.