The title of this post, as readers based in the United States surely know, refers to a statement from candidate Mitt Romney in a presidential debate. In response to a question from the audience, Romney gave the following account of his quest to identify women candidates for cabinet positions after he was elected governor of Massachusetts:

The title of this post, as readers based in the United States surely know, refers to a statement from candidate Mitt Romney in a presidential debate. In response to a question from the audience, Romney gave the following account of his quest to identify women candidates for cabinet positions after he was elected governor of Massachusetts:

“[A]ll the applicants seemed to be men. And I – and I went to my staff, and I said, ‘How come all the people for these jobs are – are all men.’ They said, ‘Well, these are the people that have the qualifications.’ And I said, ‘Well, gosh, can’t we – can’t we find some – some women that are also qualified?’ And – and so we – we took a concerted effort to go out and find women who had backgrounds that could be qualified to become members of our cabinet. I went to a number of women’s groups and said, ‘Can you help us find folks,’ and they brought us whole binders full of women.”

Amidst the hilarity that has since ensued (I recommend an Internet search for “binders full of women,” as well as a glance at this IntLawGrrls post), let’s pause to consider some data from the glamorous world of international arbitration.

Attorneys Mark Baker and Lucy Greenwood of Fulbright & Jaworski collected information about arbitrator appointments for their article, “Getting a Better Balance on International Arbitration Tribunals,” which will be published in Arbitration International by the end of this year. Based on information provided by two major international arbitration institutions, among other sources, they estimate that women represent between 4 and 6.5% of recent appointments in international commercial cases.

A similar picture emerges in investment treaty arbitration: Baker and Greenwood find that women account for 5.63% of arbitrators appointed in arbitrations administered by the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, or ICSID, and concluded between January 13, 1972, and January 18, 2012. Earlier this year, a publication entitled “The (lack of) women arbitrators in investment treaty arbitration,” by Osgoode Hall Law Professor Gus Van Harten, placed the number of women arbitrators in all known investment treaty cases until May 2010 at 6.5%.

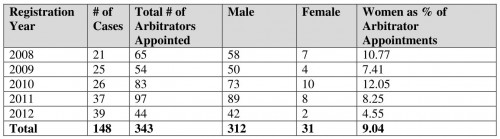

To get a sense of recent trends, I reviewed appointments in cases registered with ICSID between January 1, 2008, and October 19, 2012, with the following result:

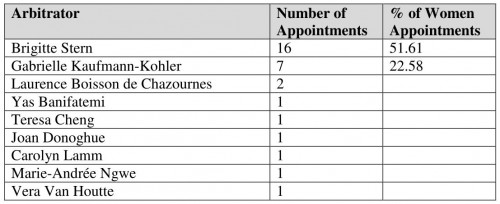

While hardly reason to uncork the Champagne, a 9.04% appointment rate is seemingly a substantial improvement over the 5.65% to 6.5% range based on longer-term data. Yet as Van Harten points out, the increase disproportionately reflects the extraordinary success of Geneva Law Professor Gabrielle Kaufmann-Kohler and Sorbonne Law Professor Brigitte Stern in obtaining appointments, and doesn’t signify a broader trend. My review of appointments made in cases registered with ICSID in the past five years confirms Van Harten’s finding that Kaufmann-Kohler and Stern (prior IntLawGrrls posts) account for approximately 75% of all women arbitrator appointments in investment treaty cases:

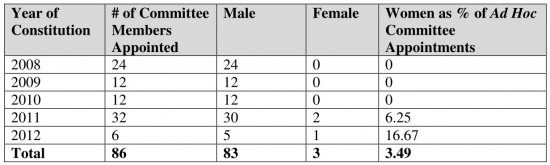

One might expect to encounter more women in annulment committees, whose members are appointed by the Chairman of the Administrative Counsel of ICSID. After all, doesn’t ICSID have greater incentives than parties to consider gender balance? Perhaps not. Women account for only 3.49% of annulment committee members appointed since 2008:

These numbers should cause disquiet in the international arbitration community. I’m sure all of us can instantly call to mind several female practitioners and scholars – in addition to Kaufmann-Kohler and Stern – who have established strong reputations. Women appear as counsel in high-profile arbitrations, win promotions in top law firms, publish articles and present at conferences. Why don’t they get appointed as arbitrators?

The attitude reflected in a recent statement (p. 2, emphasis added) from Hew Dundas, former President of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, may provide a partial explanation:

“In my time as President, I don’t recall ever thinking about gender in making appointments. I was looking at facts on a CV and choosing the best candidates for the job.”

Van Harten has suggested that the answer to the gender imbalance issue lies in actively bringing female candidates to the attention of those who select arbitrators. His proposed solution is to create a closed roster of ICSID arbitrators “based on an open and merit-based process.” He expresses the expectation that a roster system will improve the quality of ICSID arbitration, especially if the input of organizations like Women Jurists/Femmes Juristes, the International Federal of Women Lawyers, and Arbitral Women is sought to “help loosen the hold of the boys’ club.”

The story behind Romney’s binders, as clarified the day after the debate, is instructive. The binders were prepared by the Massachusetts Governments Appointments Project at its own initiative. Before and after the 2002 gubernatorial elections, MassGAP vetted women for each cabinet post and compiled information about top applicants. Its efforts paid off: two years into Romney’s term, 42% of the new appointments made by his administration were women (in the next two years, the percentage of newly appointed women in senior positions dropped to 25%).

By all means, keep poking fun at Romney’s comments. But unless and until more systemic solutions get implemented, women’s international law organizations would do well to:

► Send targeted binders full of women arbitrators to counsel in newly filed ICSID arbitrations, and

► Periodically distribute profiles to practitioners and organizations in the field.

And those of you who make appointment decisions may want to take active steps to ensure that the résumés of the best candidates, male and female, arrive at your desk – or on your computer screen.

This post also appears on the blog, IntlLawGrrls: Voices on International Law, Policy, Practice.