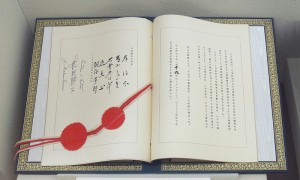

Many have noted that the U.S.-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security could pull the United States into the dispute between Japan and China over the Senkaku / Diaoyu Islands by obligating the United States to come to Japan’s defense in the event of hostilities. Article 5 of the Treaty has the key language and provides that “each Party recognizes that an armed attack against either Party in the territories under the administration of Japan would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional provisions and processes.” Because the Senkaku / Diaoyu Islands are “under the administration of Japan,” there is no question that the Treaty applies to them. For that reason, the dispute over the Islands poses a risk for the United States; if any of the nearly daily incursions by Chinese vessels into the surrounding waters turns into an “armed attack,” the United States will have a legal obligation to back Japan. Yet the precise nature of that obligation is unclear. For a couple of reasons, I think it is more limited than many have assumed.

Many have noted that the U.S.-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security could pull the United States into the dispute between Japan and China over the Senkaku / Diaoyu Islands by obligating the United States to come to Japan’s defense in the event of hostilities. Article 5 of the Treaty has the key language and provides that “each Party recognizes that an armed attack against either Party in the territories under the administration of Japan would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional provisions and processes.” Because the Senkaku / Diaoyu Islands are “under the administration of Japan,” there is no question that the Treaty applies to them. For that reason, the dispute over the Islands poses a risk for the United States; if any of the nearly daily incursions by Chinese vessels into the surrounding waters turns into an “armed attack,” the United States will have a legal obligation to back Japan. Yet the precise nature of that obligation is unclear. For a couple of reasons, I think it is more limited than many have assumed.

First, Article 5 does not necessarily require the United States to use military force in responding to an armed attack; the obligation is simply to “act to meet” the danger presented. It is not unreasonable to imagine that the United States could satisfy that obligation by pursuing economic or even diplomatic measures, depending on the circumstances. The vagueness of the text leaves Washington with significant discretion to decide whether a particular response will be enough.

Second, even assuming that only military measures can suffice, an armed attack on Japan will trigger a U.S. obligation to carry out only those measures that can be executed “in accordance with [U.S.] constitutional provisions and processes.” Significantly, those provisions and processes include Article I’s War Clause, which gives the House and Senate the exclusive power to issue declarations of war. The Treaty can legitimately obligate Congress to use that power in Japan’s defense if one assumes that the President and Senate could, simply by adopting the Treaty, require the House to cooperate in the passage of any war resolution that the Treaty subsequently demands. It is not clear, however, that the President and Senate have such a power. On one hand, a ratified treaty has the status of federal law under the Supremacy Clause. On the other hand, the House’s involvement in various Article I processes is meaningful only if the House retains power to make decisions independently. A treaty that could obligate representatives to approve a war resolution would transform their collective exercise of the war power into a mere formality and shift the true location of that power to the Senate and President. In short, the separation of powers might limit U.S. obligations under the Treaty. The only interpretation that clearly raises no constitutional problem would leave the House with an independent power to choose whether to support a war resolution, and thus preserve the possibility that the resolution fails.

More broadly, this analysis suggests that the Treaty obligates the United States to act only in ways that do not require the approval of the House of Representatives under U.S. law. Options that fall into this category include any number of diplomatic initiatives that rest on the exclusive diplomacy powers of the President, and limited military measures that rely on the President’s power as commander in chief. Article 5 thus operates somewhat perversely: the security guarantee is strongest when the measure necessary to meet the threat is modest, and weakest when the necessary measure is most robust. At best, Japan has a vague promise of limited assistance in the event of an attack. The Treaty leaves the United States with plenty of room to maneuver, but also leaves Japan vulnerable.

In this context, and given the difficulties associated with increasing the U.S. military presence in Japan, it is hard not to sympathize with Prime Minister Abe’s proposal to amend Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution to allow for a more potent military. According to Defense Department estimates, China’s military budget grew by an average of 9.7% annually from 2003 to 2012, with spending totaling somewhere between $135 and $215 billion last year. This is far less than military expenditures in the United States, which totaled $677 billion in 2012, but also noticeably more than Japanese expenditures, which saw no annual growth in the last decade and increased by only .8% to $51.7 billion in 2013. A stronger domestic force and corresponding shift away from Article 9 may be the only way for Japan to counterbalance a more assertive China.