With the Marquette Law School conference “Dividing Lines” approaching on May 15, it is worth asking why hard and determined forms of partisanship so unnerve us.

With the Marquette Law School conference “Dividing Lines” approaching on May 15, it is worth asking why hard and determined forms of partisanship so unnerve us.

The immediate occasion for this discussion is Craig Gilbert’s study of political polarization in the Milwaukee metropolitan area, and its economic and cultural origins. Gilbert is the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s Washington bureau chief and this past year served as the Law School’s Lubar Fellow for Public Policy Research. Working with Charles Franklin, professor of law and public policy and director of the Marquette Law School Poll, Gilbert has documented in recent elections a strong and consistent correlation between voting preferences and race, ethnicity, education, and population density (the series to date appearing in the newspaper here, here, and here, with the final entry coming this Wednesday). Marquette Law School’s Professor David Papke has also commented on Gilbert’s research, noting how deliberately conceived public policies such as restricted covenants, exclusionary zoning, and easing of residency rules for municipal employees have contributed to the climate of divisiveness.

As a scholar of journalism and media, I want to probe more deeply the meanings Americans attribute to their experience of political division. Partisanship, especially these days, does not want for defenders. Indeed, the country’s liberal tradition seems to invite it, emphasizing the need for robust competition between ideas in politics, and for unrestrained competition in the marketplace. These commonplaces of American life, in turn, encourage partisan individuals to style themselves as sincere and authentic in their public performances. A willingness to engage in tough-minded, agonistic argument has come to be seen as a sign of moral virtue, a principled refusal to yield to untruth.

And yet . . . we do worry about intense forms of partisanship, and for good reason. We know from our personal and historic experience how easily an unwillingness to listen, withhold judgment, or compromise can undermine the common good. True believers unsettle us because their certainty makes us wonder what they would be willing to do in order to get what they want. Moreover, each generation carries in its head a parable about partisanship run amok — a story about how the Civil War nearly brought the union to ruin, how Vietnam destroyed family comity, or how a gubernatorial election put mild-mannered Wisconsites at one another’s throats.

In a New York Times opinion piece last fall, the Canadian writer and politician Michael Ignatieff eloquently summarized the dangers to democracy from this state of affairs. Ignatieff spoke to the importance of distinguishing adversaries from enemies. “An adversary is someone you want to defeat,” he wrote. “An enemy is someone you have to destroy.” Liberal democracies depend upon the goodwill of adversaries. Ignatieff argued that appeals to civility will not diminish the current spirit of enmity, and he urged the sort of structural changes that other Western democracies use to minimize gridlock, including campaign finance rules, open primaries, and impartial redistricting commissions to avoid gerrymandering.

There is much more to be said about Craig Gilbert’s careful, thoughtful study of polarization, but let me leave that work to the May 15 conference participants and close with two observations.

First, polarization has created a tragic mismatch between the problems facing southeast Wisconsin and the political tools at hand to solve those problems. The conflicts over water for Waukesha, high-speed rail, public university funding, the Affordable Care Act, and school vouchers offer a preview of what lies ahead. Every significant challenge confronting us, from economic development to public health to environmental protection to inequality, requires a regional response. And yet we have poured all our political energy and imagination into branding, mobilization, and fundraising rather than into the arts of deliberation. We think so little of governing that we now consider it normal that candidates running for public office plainly express their distaste for government. Faced with a stalemate they themselves have created, the national parties generate preposterous bills with no chance of passage. Easier to create talking points for the next election than to do the work for which they were hired.

Second, polarization creates its own problems for journalists. I am grateful to live in a community where the legacy newspaper remains committed to public service. But how much can we expect of journalism in the absence of the structural changes that Ignatieff and Papke recommend? Whatever its blind spots, exclusions, and prejudices, the American daily newspaper that emerged after World War I believed in the reasonableness of the political system. What happens when the political system no longer puts much faith in its own reasonableness? And in the new digital media environment, wracked by its own forms of fractiousness, how might journalists who hope to speak on behalf of the common good find their feet?

John Pauly is professor of journalism and media studies in Marquette University’s Diederich College of Communication.

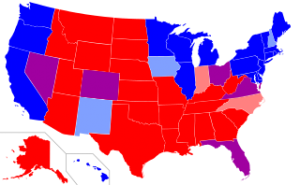

The illustration shows us in Wisconsin as blue, while some states are depicted as various shades of red and blue or are purple . . . I thought we were considered a “purple” state. Does the research show Wisconsin is now firmly dark blue?