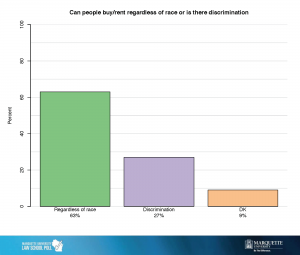

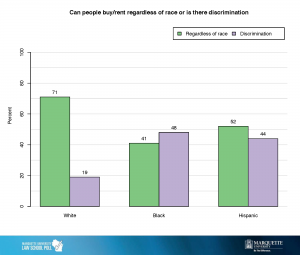

The Milwaukee Area Project’s debut poll asked respondents, “Do you think that people in your community have the opportunity to rent or purchase a home they can afford regardless of their race, or is there significant racial discrimination in housing?”

This question echoes a longer history in the Milwaukee area over access to housing. The winter of 2017-2018 marks the 50th anniversary of the “March on Milwaukee.” For two hundred consecutive nights, starting in September 1967, civil rights activists in Milwaukee marched to demand that people be allowed to buy and rent homes that they could afford without being subject to discrimination on the basis of race. At the time, it was legal for property owners to reject prospective renters or buyers because they were black.

Starting in May 1962, Alderman Vel Phillips (elected as Milwaukee’s first African American and first female city council member in 1956) proposed an ordinance that would have barred city property owners from discriminating against African Americans. Proponents of this kind of law in the United States said that it would ensure “fair housing” or “open housing”—in pointed contrast to housing that was unfair or closed. Opponents of the law, borrowing the rhetoric of “forced busing” from the contemporaneous debate about desegregation of public schools, decried what they called “forced housing.” Phillips’s ordinance was repeatedly offered and defeated by a vote of 18-1 in the years leading up to start of the marches.

Milwaukee’s open housing marches continued every night into mid-March 1968. In April, a week after the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the US enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1968. This law, also known as the Fair Housing Act, outlawed racial discrimination in housing and other practices that hobbled African Americans’ search for decent homes. By the end of April, the Milwaukee Common Council followed suit with its own fair housing ordinance. The passage of fair housing laws, however, did not in itself end racial discrimination. In 1977, a new organization, the Metropolitan Milwaukee Fair Housing Council, was created in order to help people who faced illegal discrimination.

If you are interested in learning more about the history of open housing in Milwaukee, the sources below may be helpful.

Digital Resources

Entries posted in the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee illuminate local struggles over access to housing, including:

- Civil Rights: https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/civil-rights/

- James Groppi: https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/james-groppi/

- Metropolitan Milwaukee Fair Housing Council: https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/metropolitan-milwaukee-fair-housing-council/

The award-winning digital archive March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project showcases primary sources from the archival collections of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Golda Meir Library: http://uwm.edu/marchonmilwaukee/

If you would like to dig deeper, try the following books and articles:

- Jack Dougherty, “African Americans, Civil Rights, and Race-Making in Milwaukee,” in Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past, edited by Margo Anderson and Victor R. Greene, 131-61 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004).

- Patrick D. Jones, The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009).

- Stephen Grant Meyer, As Long as They Don’t Move Next Door: Segregation and Racial Conflict in American Neighborhoods (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000).

- Erica L. Metcalfe, “‘Future Political Actors’: The Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council’s Early Fight for Identity,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 95, no. 1 (2011): 16-25. http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/wmh/id/50802/show/50759/rec/1

- Margaret Rozga, 200 Nights and One Day (Hopkins, MN: Benu Press, 2009).

- Margaret Rozga, “March on Milwaukee,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 4 (2007): 28-39. http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/wmh/id/49374/show/49373/rec/1

Master’s theses and dissertations also provide information on open housing not readily available elsewhere.

- Liane Ardell Aylward Dolezar, “Father James E. Groppi: A Case Study of Civil Rights Rhetoric” (Master’s thesis, Speech and Dramatic Art, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1969).

- Katelyn Barnes, “James Groppi: A Man and His Faith: A Biography” (Master’s thesis, History, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2011).

- Thomas R. Feld, “The Rhetoric of Father James Groppi in the Milwaukee Civil Rights Movement: A Study of the Rhetoric of Agitation” (Master’s thesis, Speech, Northern Illinois University, 1969).

- Erica L. Metcalfe, “‘Coming into Our Own’: A History of the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council, 1948-1968” (MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2010).

- Julius John Modlinski, “Commandos: A Study of a Black Organizations’ Transformation from Militant Protest to Social Service” (PhD. Diss, Social Welfare, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1978).

- Jay Anthony Wendelberger, “The Open Housing Movement in Milwaukee: Hidden Transcripts of the Urban Poor” (Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1996).

For the deeper background of African Americans in Milwaukee, see:

- Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-45 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006; originally published 1985).