Copyright and the Restatement of Torts

In my first post, I discussed the emergence of the Gershwin test and how it’s run into trouble from a combination of rigid interpretation and novel fact patterns. In my second post, I argued that this problem was made worse with the Supreme Court’s Grokster decision, which cited Gershwin and referred to contributory infringement, but discussed only intentional inducement.

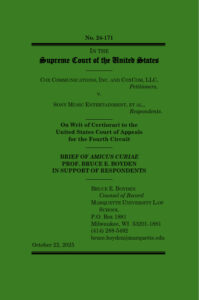

The Cox case brings the contributory liability question back before the Supreme Court for the first time since Grokster. That makes it an ideal opportunity for the Court to straighten out some of the confusion, but there is always the danger that a generalist, textualist court could instead make things worse. (See, e.g., Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands.) Doing my bit to try to avoid that result is part of the reason I spent the 100-plus hours to submit an amicus brief in this case, but not the entire reason. After all, the court gets dozens of amicus briefs in a case like this, so the marginal impact of an additional brief is near zero. (One oddity of the Supreme Court rules is that every brief, even a pro se amicus brief, is required to be filed by a “counsel of record.” So I filed the brief as counsel to myself.)

The other reason I bothered to write my brief is because I spotted a connection that I don’t think has been fully presented by anyone else. I’ve been pondering the relationship between indirect copyright liability and tort law for over a decade, so it captured my attention at the cert. stage in this case when both Cox and the Solicitor General relied heavily on Twitter v. Taamneh, decided in 2023. Taamneh had nothing to do with copyright law. Instead, the case involved claims against Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook under the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA) for “knowingly providing substantial assistance” to persons engaged in international terrorism. The Taamneh complaint alleged that the platforms knew members of ISIS were using their services, but did nothing to remove them. The Supreme Court held that that was insufficient for liability under JASTA. Otherwise, the Act “would effectively hold any sort of communication provider liable for any sort of wrongdoing merely for knowing that the wrongdoers were using its services and failing to stop them,” a conclusion that would “run roughshod over the typical limits on tort liability.”

Aha, Cox and the Solicitor General said in their cert. briefs, that’s exactly like Cox! Sony Music and some amici, on the other hand, argued that Taamneh was decided under a completely different statute, and therefore of dubious applicability to a copyright infringement claim, particularly one with more compelling facts about the defendant’s involvement.

I don’t think either side of this debate has it quite right. Cox and its amici are correct that there’s a deep connection between civil aiding and abetting liability, the subject of a lengthy analysis in Taamneh, and contributory liability in copyright law. But that connection has to do with the legal doctrine and how it’s applied. Sony Music and its amici are correct that factually, this case is far different from Taamneh, in a way that justifies sending it to a jury — which it was, and the jury had all the tools it needed to decide the case under a civil aiding and abetting framework. I’m a bit ambivalent about the use of juries to decide complicated copyright policy questions, but the Supreme Court for the most part isn’t, and this case went to a well-informed and properly-instructed jury that decided against Cox.