A Call to All Law Students: Enhancing the National Conversation

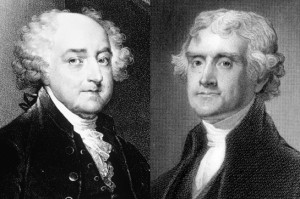

“I consider you and [Jefferson] as the North and South Poles of the American Revolution. Some talked, some rewrote, and some fought to promote and establish it, but you and Mr. Jefferson thought for us all.”

—Benjamin Rush to John Adams, February 17, 1812

Every law student has a responsibly to enhance the American Conversation—the eternal dialogue that is the American experiment. While it would be conceited and with reproach that I suggest we think like Messrs. Adams and Jefferson, we should, however, seek to become more thoughtful and attempt to engage in lively, educated discourse. Our national dialogue has increasingly been filled with a self-destructive, dysfunctional, do-nothing mentality that lacks reasoned thought. This trend is at best unproductive—at worst, destructive—to the American Conversation. As law students, we have the skills and responsibility to change this trend.

It is quite gratifying to obtain a deep understanding of a topic and then learn that you lacked a full appreciation for some of the more nuanced issues within that particular topic. Part of the legal learning process encapsulates this type of learning, where you learn a new approach or different perspective and it can—and should—be learned outside the classroom. It should go without saying that one the best places to learn is outside the classroom. But as law students, in the ultra-competitive school environment, we tend to focus on grades (and the job hunt) and lose focus of the big picture—developing the skills necessary to fulfill our duty to serve the public. As such, we would do well to be reminded of the importance of using the skills we have learned outside the classroom. While Dean Kearney reminds us to continue learning outside the classroom (e.g., in the many guest lectures, at On The Issues, and during social and award events at the Law School), the one place for learning that should continually reside in a predominant place in our minds is the Zilber Forum, a social area for discussion and contemplation. The Zilber Forum, or the idea of the Forum, does not and should not stay within the confines of the four walls (although the shape of the building may suggest three). This idea is already bursting at the seams of Eckstein Hall and with a little help from students will reach the community around us.