Let me again extend my appreciation to Deans Kearney and O’Hear for the opportunity to serve as December’s guest alumnus blogger of the month, and to all of you who joined the conversation in the comments section. I’ll be right there with you starting tomorrow. 🙂 Let me also take advantage of my month’s unique position on the calendar to wish you all a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year.

Let me again extend my appreciation to Deans Kearney and O’Hear for the opportunity to serve as December’s guest alumnus blogger of the month, and to all of you who joined the conversation in the comments section. I’ll be right there with you starting tomorrow. 🙂 Let me also take advantage of my month’s unique position on the calendar to wish you all a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year.

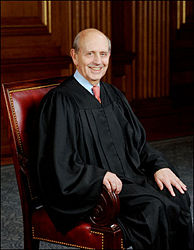

My final post is, in fact, the abstract of a piece I have just posted to SSRN. Earlier this year, you may have seen that Fordham’s law school received some heat from Edward Cardinal Egan, Archbishop of New York, for its decision to confer an award on pro-abortion Justice Stephen Breyer. The story led me to do some investigating, drawing in part on my own experiences as a Marquette student, and voila, an essay emerged. I hope to begin shopping it around to law reviews in the spring submission season.

Here’s the abstract:

In the fall of 2004, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops promulgated a statement titled Catholics in Political Life , which included this provision: “The Catholic community and Catholic institutions should not honor those who act in defiance of our fundamental moral principles. They should not be given awards, honors or platforms which would suggest support for their actions.”

Since the statement’s adoption, a number of Catholic institutions, including law schools at Catholic universities, have issued invitations to speakers and honorees who are pro-abortion or pro-gay marriage. In several instances, the local bishop gave a public or private rebuke to the law school for doing so. These episcopal criticisms often lead to a news story and an outcry from students, alumni, and area Catholics, bringing further embarrassment to the school.

My hope is that this essay will help law school deans and other university administrators navigate the tensions inherent in making these invitations, all with an eye on avoiding awkward situations. The essay begins by recounting the history of the statement’s passage by the USCCB. It then collects a number of examples where bishops and universities have clashed over invited speakers and honorees. Finally, it offers lessons for law school deans, urging them to pursue dialogue with stakeholders before making invitations that could come within the statement’s scope.

Excellent points, Daniel. It’s imperative that we all work to avoid these potentially awkward and embarrassing situations.

It’s precisely law schools that should be at the vanguard in promulgating viewpoint-based discrimination, particularly where those viewpoints issue from heretical interpretations of constitutional jurisprudence.

Let’s begin by demanding the immediate dismissal of all the “pro-gay marriage” faculty at Marquette. We know who they are.

Next we’ll weed out the local “New Federalism” sympathizers, those ones who are “pro-criminal” by definition.

And, of course, no more standing invites from the Marquette chapter of the Federalist Society to the aggressively “pro-death penalty” Justice Scalia.

Finally, in following Patrick J. Reilly‘s courageous leadership, let’s ensure that our infallible hermeneutic extends even to the family and friends of would-be moral transgressors who dare challenge the Church’s position on, say, stem cell research.

Heck, while we’re at it, let’s make William Donohue an adjunct professor.

Mr. Foley:

My essay is a balanced approach that at bottom urges increased dialogue and conversation. Such a tact serves both the interest of the bishop in protecting the Catholic identity of institutions entrusted to his care and the interests of the dean in avoiding negative news exposure and community criticism (and the dean’s own interest in a faithful presentation of her school’s chosen identity).

Nowhere in the essay do I discuss tenured professors’ rights to academic freedom. Any “viewpoint discrimination” is a consequence of the institution’s choice to call itself Catholic and therefore to obey the instructions of Catholic authorities. Moreover, it is limited to particular types of high-profile events, “awards, honors or platforms that suggest support for their actions.”

Furthermore, the death penalty is a creature of a different nature than stem cell research, abortion, and gay marriage; the Church’s opposition to it is a matter of prudential judgment on which faithful Catholics may legitimately disagree, whereas the latter issues are definitive issues of natural law.

Of course, the kind of conversations that I hope will happen will succeed only if they involve people of good will interested more in honest cooperation than partisan points.

I don’t want to jump to the same conclusions Tom has, but ARE you in fact suggesting that institutions like Marquette Law follow the provision listed in the first paragraph of the excerpt? Because if you are not, I would argue that the first paragraph sets entirely the wrong tone for an abstract if your intent is to portray your piece.

I understand Marquette is a private university and can do (within reason) just about whatever they want. Frankly, I’m grateful that I haven’t been subjected to the forcing of faith down my throat, unless you consider the Benediction — is that the right term? — given at University gatherings to constitute that (and I don’t). However, if we were to limit the law school to the provision listed above, wouldn’t we lose a lot of great speakers who just don’t happen to be Catholic? And, by the way, I’m a Jew; wouldn’t “honor[ing] those who act in defiance of our fundamental moral principles” extend to include prohibiting me from graduating? For that matter, I find it hard to believe that there’s anyone here who can argue that they haven’t acted in some way that runs counter to the “fundamental moral principles” of the Catholic faith — I know people who live in sin before marriage, who have had children out of wedlock, who lie, who steal, who fail to tithe to the community, who do bad deeds unto one another, who fail to turn the other cheek, who fail to FORGIVE — so wouldn’t those people be precluded as well? And if you eliminate all those people, who is left?

I’m not trying to come down hard on you by any means, but I’m wary of the advocacy of any faith-based guidelines for any school. Being a Jesuit school doesn’t mean that you have to exclude others who aren’t. Jesus preached tolerance and acceptance, after all, so what would Jesus say if he read this?

I am stating positively that Marquette, in choosing to continue to call itself Catholic, has agreed to abide by the provision in the first paragraph of the abstract.

Marquette may be able to do whatever it wants because it is private and not subject to the First Amendment, but it may not do whatever it wants and call itself Catholic. Because it chooses to be a Catholic institution, it assumes certain rights and responsibilities, including this one.

And I’m not saying that anyone needs to get up behind a podium and deliver a lecture of Catholic apologetics. I’ll note here that I’m not Catholic either. And the statement does not prohibit honoring non-Catholics – far from it. The statement prohibits honoring anyone, Catholic or non-Catholic, who “acts in defiance of our fundamental moral principles.” As you note, that is a somewhat ambiguous phrase – the bishops nowhere define what constitutes a “fundamental moral principle.” One contribution of the article, then, is to look at the actions bishops have taken since the statement was issued and draw meaning from them. In every instance I have found, the test was public, vocalized support for abortion or gay marriage.

Jesus preached truth, and we can know truth through reason and the natural law. The expectation of the bishops is that Catholic institutions will not compromise the witness of the Church in the public square for life and family by honoring those who support policies that destroy life and family.

Not conclusions exactly, Andrew, but if any institution should be open to the airing and reception of competing ideas, it’s a law school.

Furthermore, I daresay, a Jesuit law school especially, since the Jesuits have an impressive and well deserved reputation for fearless intellectual engagement.

They’ve also a considerable leftist — and I mean leftist in a substantive sense rather than as the cheap epithet tossed about indiscriminately by GOP talkers — contingent. See, e.g., liberation theology.

The bishops’ provision may be a suitable admonition to Liberty or Regent law schools, however.

And Daniel, as for “partisan points,” authoring an opinion following Roe and Casey does not necessarily make one “pro-abortion.”

Justice Breyer may very well be “anti-abortion” but the law leads him elsewhere when it comes to determining how it should apply to other people, other peoples’ private consciences and sincerely held beliefs, and in particular the criminal culpability of physicians and their patients (the central issue in Stenberg).

Labeling him “pro-abortion” from the outset is little more than a transparently fallacious attempt at poisoning the well.

The Jesuits, as historically expert logicians, would doubtless agree.

The statement prohibits honoring anyone, Catholic or non-Catholic, who “acts in defiance of our fundamental moral principles.” As you note, that is a somewhat ambiguous phrase – the bishops nowhere define what constitutes a “fundamental moral principle.” […] In every instance I have found, the test was public, vocalized support for abortion or gay marriage.

Okay. Well, allow me to pose a hypothetical to you, one that I find plausible. Given that I run PILS, suppose I awarded a PILS fellowship to someone who planned to work for a non-profit gay rights firm. Or, alternately, suppose I strongly advocated for people considering applying for a PILS fellowship to look for firms of that ilk, in such a way that it was clear to anyone who spoke to me that I supported gay rights. Would I then be precluded from graduating? From being honored with any awards or special recognition the law school might choose to bestow upon me, if they wanted to? And, for that matter, I’m proud to say that someone I consider to be a close friend at this law school is openly gay. Should he be prohibited from graduating, given that I’m fairly positive he’d support giving himself rights? Should I, given that I’m announcing here and now in a public forum that I would gladly fight for his right to marry another man? Should he or I have been precluded from being admitted to Marquette Law in the first place?

I don’t believe that Marquette has any more obligation to support that provision than you, by calling yourself a Marquette Law alumnus, are obligated to follow the words of Dean Joseph Kearney when he states that:

“As a Catholic and Jesuit law school, we have a particular obligation to assure that the education that is provided at Marquette is designed to enhance our students’ respect for all people . . . to become agents for positive change in society . . . to use law as an engine for positive change, not as a device to cause anger and unhappiness“. Wouldn’t a fundamental principle of respecting others and using law as an agent for positive change be support for the rights of all people, regardless of their race, gender, or sexual orientation?

Subscribing to a faith has never meant agreeing to rigidly follow dogmatic principles. If that were so, Christianity would never have existed, for what did Jesus do but to cast off the prevailing faith and lead his disciples to another one? If the very symbol of a faith represents interpreting the rules so as to provide the greatest benefit of humanity, why shouldn’t Marquette — or any other Jesuit law school, for that matter — do the same? The answer is that it can, and, as a Jew and as a person who would very clearly be ostracized by the provision whose adoption you advocate, I can’t help but feel a bit offended at the idea that my rights and beliefs should be somehow inferior to other members of the Marquette community who better follow the “fundamental moral principles” than I do. It certainly sounds like that’s what you’re implying.

Think tanks may be placed where ideas are bandied about. Congress may be a place where ideas are openly tested against one another. Law schools should be interested in training students as lawyers, and Catholic law schools claim to do so in a unique way. That unique way includes an intellectual tradition grounded in natural law that can be known by human reason.

And yes, the Jesuits are “leftists,” and that is a large part of the problem. See the extended discussion in footnote 121. Regent and Liberty aren’t Catholic, but if they were, the bishops wouldn’t need to admonish about them honoring pro-abortion politicians. It’s the universities sponsored by Jesuits and other groups that are handing them out, and that’s precisely the problem (“scandal” in the theological sense) that the bishops are targeting. In handing out these awards to pro-abortion public figures, these schools were going “off-message” and confusing people. This provision is a way to get them back “on message” on these fundamental moral issues.

As for the second point regarding judges, I have dealt with this on page 23.

Your comment, Andrew, extrapolates way beyond what I (or, for that matter, the bishops) have said. On the surface, you may be able to plausibly say that such a PILS president is “acting in defiance of our fundamental moral principles.” But this is why it’s so important to look at what the bishops have done in the past four years; it gives us a much better sense of what they actually meant. And that’s the contribution of the article. We can look at the practices of the individual bishops in the last four years, and see that never once has it been applied against a student. Now, that’s not to say that it won’t be in the future, but I very highly doubt it. And even if that were ever the case, it would at most extend to giving the PILS president an award at the end of his time there; graduating with your class upon earning your degree simply is not an “honor, award or platform.”

I appreciate your quotation from Dean Kearney. However, his quote discusses the law school’s aspirations for its alumni – the “particular obligation” is upon the law school to teach certain things – it imposes no obligation on me as a person who calls myself a Marquette Lawyer.

The USCCB statement, however, is a rule issued by those with authority to issue rules, only in this instance one chooses to come under their authority. When your softball team captain says that “In order to be on this team, you must wear a red uniform,” you choose to be on the team and you voluntarily assume the obligation to wear a red uniform. You could choose to play for the blue team, or for no team. Same here – Marquette chooses to call itself Catholic, and so chooses to follow the Catholic rules, including this one.

I’m also quite in agreement that we must respect the rights of all people regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation. The difference is that we disagree about what rights people have, such as whether any individual has a right to marry any other individual.

Subscribing to a faith can mean required subscription to a series of dogmatic principles. Some faiths do not require this, perhaps (I’m not an expert, but I imagine this would be true of Unitarian Universalists). But for other faiths, most faiths, one must subscribe to dogmatic principles (though the length of the list of required principles may vary). When I was confirmed in the Lutheran Church, I stated my belief in the Apostle’s Creed. To believe something other than the Apostle’s Creed is my option, but it necessarily means I am rejecting the Lutheran faith.

As for “interpreting the rules for the greatest benefit of humanity…” First of all, this supposes interpretation. But sometimes the rules are so clear that they require no interpretation. I would submit that the sinfulness of homosexual activity is one such rule. Even were that not the case, we would disagree about whether it is to “the greatest benefit of humanity” to allow homosexual marriage.

Also, I am not advocating the adoption of a provision. The provision has been adopted by the relevant authority. I am trying to help people understand the provision, because currently there’s confusion about it.

As to feeling “ostracized,” let me say this: in Criminal Law I, we learn that one purpose of the criminal law is to teach those who break it that what they did was wrong. All the time, our society uses awards to reward good behavior and the denial of awards or the imposition of punishments to punish bad behavior.

To the extent anyone feels ostracized because they cannot get these awards because of their positions on certain issues, I think the bishops would hope you have “a teaching

moment” that results in your reconsideration of your position on those issues.

Finally, I need to add an asterisk to my earlier comment and say that obviously not all Jesuits are leftists. The late Avery Cardinal Dulles, for instance, was a great man of the Church, entirely faithful, devout, and obedient. There are many individual Jesuits and collections of Jesuits who are not “leftists,” and being a “leftist” does not necessarily mean being less devout or less faithful. However, as I note in footnote 121, many authorities recognize that some orders, including the Jesuits, have a significant chunk of the membership that is currently distant from the hierarchy. The term “leftist” is very crude, but since it’s the one he chose, it’s the one I used.

I ought to also drop a footnote here acknowledging Marquette’s special role in the history of what has been called “the Catholic identity movement” among law schools.

In 1994, Marquette hosted the first conference of what would become the Association of Religiously-Affiliated Law Schools (ARALS). The papers from that seminal gathering are published in volume 78 of the Marquette Law Review. Speakers included Rex Lee, founding dean of the BYU Law School; Tom Shaffer, former dean of Notre Dame; and Tim O’Meara, provost of Notre Dame. The conference continues to this day.

Later, Dean Howard Eisenberg served as president of ARALS. He delivered an oft-cited paper at a conference of ARALS entitled “Mission, Marketing, and Academic Freedom in Today’s Religiously Affiliated Law School.” 11 Regent U. L. Rev. 1 (1998). Of course, his speech “What’s a Nice Jewish Boy Like Me Doing in a Place Like This?” is also an insightful look at Catholic legal education. 86 Marq. L. Rev. 336 (2002). In doing so, he followed in the footsteps of an earlier (interim) dean, Steven M. Barkan. Jesuit Legal Education: Focusing the Vision, 74 Marq. L. Rev. 99 (1990).

To your helpful list of Marquette-ARALS connections, you can add my presentation to the ARALS Conference in 2006. The paper, “Faith, Justice, and the Teaching of Criminal Procedure,” was published in the Marquette Law Review, and is available here: http://law.marquette.edu/lawreview/Fall%202006/10-O'Hear%20Essay%20(post%20edit).pdf.

Mr. Suhr has raised an important question that deserves a serious discussion. Too often these sorts of questions lead to a lot of heat with little illumination. I offer these thoughts in hope of advancing the discussion, and with no claim to be an expert on these issues.

As the discussion has developed in the comments, it appears that the true issue has emerged: Who is the Catholic Church? The Church is the people of faith (technically, the highest authority on matters of doctrine is the Council of Bishops, but that does not make the Council synonomous with the Catholic Church). The Church itself is not embodied in either the Pope or any other official body.

Most of the contentious debates among the faithful surround the Church doctrine holding that sex is immoral if it does not lead to procreation. Vatican II flirted with the idea of abandoning this doctrine (or modifying it, or else Vatican II firmly upheld it — pick your interpretation of what transpired). Is it possible for the Church’s moral teachings to change over time? Of course, so long as they do not come into conflict with the Nicean Creed (the doctrine of the trinity and the death and resurrection of Jesus).

In fact, the Church once ordered the torture and execution of dissidents. It now considers both practices immoral. Change happens. Moral doctrine is not permanent.

Conservatives within the Church fear that abandoning the Church’s teachings on sex will lead to the faithful questioning other longstanding moral doctrines. They would prefer any change to be gradual, if it occurs at all. Liberals want change NOW.

There are parallels here to the battle over civil rights for African-Americans. Conservatives said, “Be patient, it will happen eventually.” Liberals convinced the Supreme Court to impose change on a faster timetable.

My point is that the doctrinal debate within the Church is healthy and that the role of Marquette University should be to foster a responsible debate, not to foreclose any questioning of authority. Dissidents to Church doctrine play an important role in the life of the Church. Jesuits have historically been accused of being too accepting of change, primarily because the Jesuits have been quicker to embrace scientific and political developments in the secular world than some other elements within the Church.

The doctrinal debate within the Church also points to another issue: lack of leadership. The pedophilia scandal in the U.S. is in some respects the Church’s “Katrina moment.” This event demonstrated to many faithful that a blind faith in institutions will eventually be betrayed by the imperfect humans who run those institutions. The answer is not to abandon the faith, but to seek better leaders.

(When a majority of Catholics report that they ignored the entreaties of their Bishops and voted for Barack Obama, it makes no sense to blame the flock for failing to follow. The fault must lie with the leaders who failed to inspire.)

The British Commonwealth benefited as a political entity when the aristocracy withered and leadership posts opened to the middle class. There was a lot of human talent there.

No economic enterprise would choose to hire from a pool that excluded female candidates, married candidates, and non-celibate homosexuals. There is too much human talent there to ignore.

In my personal (imperfect) opinion, the Catholic Church needs leaders who recognize the vital role of doctrinal debate and who are willing to engage in that debate. We need leaders who are open to possible changes in the Church’s moral teachings, and who are not afraid of change. And we need a laity that is not afraid to demand more of its leaders.

Hey Professor Fallone. Thanks for the comment.

I’ll agree that it’s important for universities to participate in debate about controversial public issues. While I don’t think that a Catholic school is required to sponsor such debates (you can be Ave Maria Univ. if you want to), I also don’t think a school violates the rule by sponsoring academic discussion of moral issues. Thus, as I note in the article, presentations by credentialed pro-abortion people that are intellectually rigorous and open to debate/Q&A should not be affected by the rule.

At the same time, I think you can easily distinguish between those presentations and the honors & awards affected by this provision. There’s no debate or discussion or academic rigorousness to an honorary doctorate presentation or commencement address. Thus, the bishops are able to battle confusion among the faithful (“scandal” in the theological sense) by prohibiting these honors without significantly curtailing core values of academic freedom and openness to dialogue.

I also acknowledge (see footnote 128, quoting Wolfe) that the bishops are fallible people who will sometimes make incorrect prudential judgments. But by joining Catholicism, a person subscribes to a faith system that necessarily includes an ecclesiology with authority and a polity of hierarchy. As Marquette chooses to call itself Catholic, it agrees to play by a certain set of rules that are promulgated by these authorities, including this one.

I should also acknowledge, btw, the contribution of Michael J. Mazza, Law ’99, adjunct professor of law (http://law.marquette.edu/cgi-bin/site.pl?10905&userID=2685), who authored “May a Catholic University Have a Catholic Faculty?” 78 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1329 (2003).