Next week marks both the opening day of the baseball season in Milwaukee and the finals of the Jenkins Moot Court competition. Few recognize the historical connection between these two events.

Next week marks both the opening day of the baseball season in Milwaukee and the finals of the Jenkins Moot Court competition. Few recognize the historical connection between these two events.

The moot court competition is named for James G. Jenkins, the first dean of the Law School whose bust adorns the waiting area outside the elevator stop on the second floor of Sensenbrenner Hall. What is not very well known is that Jenkins was also instrumental in the re-establishment of baseball in Milwaukee after the Civil War.

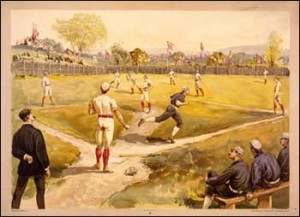

The first modern baseball club, i.e., one playing by the so-called New York rules that mark the beginning of baseball as we now know it, was established in Milwaukee in 1860. This amateur organization, known as the Milwaukee Baseball Club, featured more members of the bar than any other occupation. Jenkins arrived in Milwaukee (from New York) in 1857, and was probably a member of this first club.

Unfortunately, the Milwaukee Baseball Club folded during the Civil War, and Milwaukee reverted to the status of a “city with no modern baseball club.” However, baseball was restored on August 17, 1865, when a new club was organized headed by stationer H. H. West and lawyers Samuel Howard and James G. Jenkins. When the club reorganized in October with a written constitution and by-laws, West and Jenkins were elected president and vice-president of the club, now dubbed the Cream City Baseball Club of Milwaukee. (Cream city referred to the distinctive color of bricks widely used in the construction of mid-nineteenth-century Milwaukee.)

The new club’s first game was played on November 7, 1865, and was the result of a challenge from a group of young baseball enthusiasts (many of which were also members of the Cream City club). The challengers batted first, and when the Cream City club took the field, who should be on the mound but our own James G. Jenkins? When it was the home team’s turn to bat, Jenkins also led off the batting order.

The game was scheduled for nine innings, but was called after seven because of darkness. Pitching underhanded in the style of the time, the 31-year old Jenkins took a 14-10 lead into the fourth inning before his opponents really figured out his pitching. Jenkins gave up ten runs in the fourt and eleven more in the sixth, and while the Cream City players had no trouble scoring runs themselves, they ended up on the short end a 36-30 score.

Early box scores recorded only name, position, runs, and outs made, but Jenkins appears to have had a successful day at the plate (which was square), scoring four runs and making only 2 outs.

A number of additional matches were played that November, and in April of 1866, the club organized for the new season in Jenkins’ office. (He was then the Milwaukee city attorney.) However, the level of Jenkins’ involvement with the club as both an official and a player began to wane after that. His focus increasingly turned to politics, and though unsuccessful, he was later the candidate of the Democratic Party for governor and the United States Senate. He did go on to a lengthy career as a federal judge and ended his public career as the dean of the Marquette Law School from 1908 to 1916.

Much of this information is taken from Dennis Pajot’s wonderful new book, The Rise of Milwaukee Baseball: The Cream City from Midwestern Outpost to the Major Leagues, 1859-1901 (McFarland & Company 2009). For a biographical profile of Jenkins, see here.

Thanks for this great post, Gordon. It’s wonderful to read about Dean Jenkins’ interest in baseball. I think he would be pleased that the Jenkins Honors Moot Court Competition is named after him; he would have enjoyed the competitive spirit of the event. It’s fitting that the Brewers are starting their season at home this week a day before the Jenkins final rounds.