One of the many unusual features of the Electoral College established by Article II, Section 1, of the United States Constitution is the provision that specifies that each state shall have “a Number of Electors equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.”

One of the many unusual features of the Electoral College established by Article II, Section 1, of the United States Constitution is the provision that specifies that each state shall have “a Number of Electors equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.”

The one obvious consequence of this provision is to enhance the influence of the smaller states in the selection of the president. Because of this provision, smaller states are disproportionately represented in the Electoral College. For example, the 12 smallest states today—Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming together account for only 17 (of 435) representatives in the House, or 3.9% of the total. However, in the Electoral College, thanks to the “Senate bump,” the same states account for 41 electoral votes, or 7.6% of the total of 538.

Would the history of American presidential elections have been different, had this non-democratic element not been added to the Electoral College formula in 1787? What if Electoral votes were calculated only on the basis of the number of representatives in the House of Representatives? Have some presidential candidates been elected only because they captured the electoral votes of a disproportionate number of small states?

It turns out that the answer to the last question is yes, although the results of only three of the fifty-six presidential elections have been effected. Not surprisingly, the three affected elections are also the three closest in American history.

The first was the Hayes-Tilden Election of 1876. Widespread voter intimidation and corruption in the South made it impossible to determine which of the conflicting returns from South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana were accurate, and Congress ended up establishing a special Election Commission composed of Senators, Representatives, and Supreme Court justices to sort out the mess. Apart from the merits of the Commission’s decision, the official count produced the closest finish in history, with Hayes edging Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185-184. However, Hayes carried 21 states to Tilden’s 17. Had it not been for the assignment of two additional electoral votes to each state, Tilden would have prevailed, the rulings of the Electoral Commission notwithstanding, 150-143.

The second affected election occurred in 1916 when Democrat Woodrow Wilson ran for reelection against Charles Evans Hughes who stepped down from the Supreme Court to run for president. In an election in which Wilson’s slogan was the ironic “He kept us out of war,” Wilson edged Hughes by a margin of 23 electoral votes, 277-254. In sharp contrast to the late twentieth and twenty-first century pattern, the Republican Hughes’ support was concentrated in urban areas in the North and Midwest, while Wilson was strongest in the smaller states of the West and South. Wilson ended up carrying 30 states to Hughes’ 18, and if the two additional votes were to be subtracted for each state, Hughes would have prevailed 218-217.

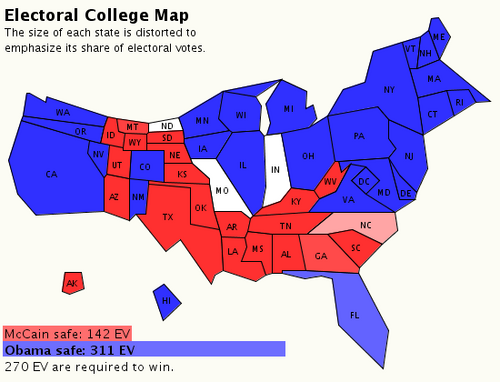

The third election was the 2000 presidential election in which George W. Bush defeated Al Gore, albeit not without great controversy, by a margin of 271-266 electoral votes. (The total electoral vote was 537 because one Gore elector refused to cast his ballot.) As in 1916, but with the parties switched, Bush carried most of the smaller states while Gore’s support was stronger in the larger, more urban states. With the two electoral vote bump removed, Gore would have won 225-211.

If we view the “Senate bump” in the Electoral College as undesirable, nothing short of a constitutional amendment can completely remove it. A dramatic increase in the size of the House of Representatives, which is within the power of Congress, could have almost the same effect, in that the value of the extra two votes would be minimized, if there were, say, 870 members of the House of Representatives rather than 435. However, a much larger House of Representatives does seem to be an item on anyone’s political agenda.

That the Electoral College with its strange features has survived for more than two centuries (and with no modification since 1804) is more than anything else a tribute to the stability of American politics and the narrowness of the American political spectrum. Compared to most European countries, the left and the right in American politics are so close together that presidential elections usually have little real effect on the direction of the country. The Electoral College may produce an occasional unfair result, but so far the consequences of the unfair results have not been significant enough to inspire a large numbers of Americans to demand change in the current system.

Professor Hylton,

If I may paraphrase your points. The electoral college and its overrepresentation of small states has changed the results of 3 presidential elections. But what is the benefit of the present system? Are small state interests being protected, or is it just a relic of the 18th century that doesn’t even function as the framers of the constitution intended?

Second, isn’t the long history of relative political moderation a result of our political culture and on the winner take all aspect of presidential and congressional elections? How would changing the electoral college, or eliminating it by constitional amendment change American political culture?

These are very interesting points.

The present system gives a slight advantage to the presidential candidate who carries the most states. In some cases, this means the winner did not have the overall popular support possessed by the loser. I suppose that this validates the role of the state in the American constitutional order. States are more than just the sum of the people who reside within their boundaries.

One is tempted to say that the removal of the current constitutional apparatus would expand the range of viewpoints. On the other hand, no state has yet been able to maintain a multi-party (i.e., more than two party) political system, even though the institutional constraints are not as imposing.

Several states had multi-party political systems in the 20th century–Wisconsin in the 1930’s and 40’s, California in the 1930’s, New York in the 1940’s and 1950’s–but they were not able to sustain themselves.

I’m not sure that constitutional changes would necessarily widen the political spectrum.

“States are more than just the sum of the people who reside within their boundaries.”

Is that still true for the majority of people? Is it true for, say, D.C., Northern Virginia and parts of Maryland? Aren’t most people these days clustered around metro areas, like D.C./Northern Virginia/Maryland, New York City/North Jersey/Connecticut/ or even confluences of major interstates, whether they be in 1, 2 or 3 states? I grew up in South Jersey, just 10 miles outside of Philadelphia. Culturally, I probably had more in common with someone living just across the river in Pennsylvania, or even someone living in Northern Delaware, than I did with someone living in, say Bergen or Essex County. And those people had more in common with their friends across the Hudson in New York than they did with me.

The only real solution to fixing the Electoral College, without attempting to amend the Constitution, is to increase the size of the House of Representatives. There is no good reason that the House has been capped at 435 members for over a century while the USA’s population has more than doubled in that time. Why is the number 435 treated as if it is sacred? It is time for a change.

While it would be too unwieldy to increase the size of the House to a number like 6,000 members as I read on one blog — which would bring the body back into line with the proportional representation it boasted in 1789 — the current total of 435 has not kept pace with the nation’s population growth in any meaningful way over the last century. Of course there is no real magic number.

Nonetheless the main goal accomplished by making the House bigger would be getting us closer to the “one person, one vote” principle that the country followed for so long. Today the smallish size of the House and the negative effects of Gerrymandering have resulted in Congressional districts of ridiculously varying sizes. A larger House would allow the return of similarly sized districts.

I say the House of Representatives should go to 701 members. This is because the population of the USA will hit 350,000,000 in the next few decades. Having 701 members, with the one thrown in to prevent ties when voting on legislation and to ensure that D.C. gets a Representative, allows for a ratio of just under 500,000 people per district. It isn’t ideal but better than the current situation.

As for questions like where to seat and provide office space for the 266 new Representatives, the House Chamber can be redesigned to accommodate more seats, and additional offices can be built, either on top of the current two wings of the Capitol Building, or in auxiliary buildings. The main thing is that groups which want an increase must unite on a number and I think it should be 701.

Why not give percentage votes per state and add them all up at the end to determine the electoral college winner? For example, Florida has 29 electoral votes and Trump received 49.1% of the vote in that state. Therefore he would receive 49.1% of the 29 electoral votes … which equals 14.24. HRC received 47.8% of the vote in Florida equaling 13.86 electoral votes. Do this for each state, add them up for all 50 states and obviously the candidate with the more electoral votes wins the Electoral College. Get rid of 270 needed to win, get rid of the winner take all for the state, and get rid of an Electoral College winner alone determining the POTUS.

I used to favor the adoption of the Maine and Nebraska system in every state. Under that approach, the winner of each state gets two electoral votes and the winner of each Congressional district gets one vote.

For example, in 2016, Trump would have received 2 electoral votes from Wisconsin for carrying the state, plus 6 more for carrying 6 of the 8 congressional districts. H. Clinton would have received the other two.

In 2012, Obama and Romney would have each received 5 electoral votes from Wisconsin under this system. Although Obama carried the state as a whole, Romney won 5 of the 8 districts.

I have backed away from this view, however, because of the effect of gerrymandering. By creating lop-sided districts in which one party has a large majority, the other party can insure victory in a larger number of districts.

Both Trump and Romney would have been elected had this system been in place in 2016 and 2012, respectively, even though both received fewer total votes than their Democratic opponents.

The Congressional Democrats in 1877 agreed not to contest Hayes’ electoral college victory on the agreement that Federal troops, which enforced reconstruction laws, be removed from those states that were in rebellion. This energized the KKK everywhere and the widespread adoption of Jim Crow laws and custom.

Bush’s illicit election led to the neocon war debacles in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Elections and how we do them, have consequences.

The overweighting of the Senate, the Electoral College as well as the 2nd Amendment were sop to the slavers in the smaller states to form and maintain the union. The first 80 years of the union were scarred by ethical and legal compromises to maintain the Union by maintaining slave-state rights to dehumanize people.

Had Lincoln served his second term, perhaps he would have convened a new constitutional convention of sorts to wipe the stains of slavery from the law of the land.