Let us review Part I. We asked the question: What causes people to be successful in their careers? I provided my own answer to that question. I believe that those who understand and develop their “soft side skills,” not just “technical skills,” will be the most successful. Clear evidence exists that career success stems as much from people skills as from technical skills. In fact, we noted that researchers at Harvard, the Carnegie Foundation, and Stanford Research Center have all concluded that 85 percent of job success comes from people skills—only 15 percent comes from technical skills and knowledge.[1] Perhaps this percentage is overstated, but there is no question that there are no professional jobs where communication excellence does not contribute to life success. Many people who pursue a professional career think of their “work” as their technical expertise, but as one takes on more and more responsibility, it becomes clear that managing or dealing with people is of equal significance.

Communication as a Premier People Skill

We also noted that effective communication represents one of the most significant elements in what are called the people skills. One-on-one conversation, coaching and mentoring, team leadership, group discussion, public speaking, persuasive writing, visual communication, and nonverbal body language are just some of the many elements that constitute effective human communication. Recently, the Internet has introduced entirely new forms of communication, such as tweeting and blogging.

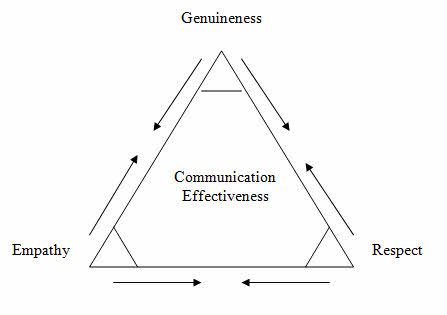

We also demonstrated how communication thinking and communication skills drove success in the legal field as well as business.[2] In order to structure this material on communication as the most significant element of people skills, we remarked that researchers in the behavioral sciences, as well as communication scholars, often suggest three characteristics that provide a foundation for communication: genuineness, respect, and empathy.[3] This model comes from the book titled People Skills: How to Assert Yourself, Listen to Others, and Resolve Conflicts, by Robert Bolton. The reader might ask why the emphasis on the opinions of one psychologist. This psychologist, Robert Bolton, is considered by the experts in the fields of communication and people skills as one of the premier thinkers on people skills for the 20th century. Bolton and his book are featured in The 50 Psychology Classics, a work by Tom Butler-Bowdon on the fifty psychologists most influential during the 20th century.[4] Butler-Bowdon comments that People Skills has been around for a quarter of a century and still sells well. The book incorporates the intellectual foundations created by Carl Rogers, Sigmund Freud, and Karen Horney, three preeminent thought leaders concerning psychological constructs. Bolton’s book does not try to cover all aspects of people skills and communication, but focuses on three learnable skills: listening, asserting, and resolving conflict. Bolton rejects the idea that having well-grounded people skills is equal to manipulation or over-the-top persuasion. As we mentioned in our first blog, Bolton comes back again and again to the three attitudes which produce good relationships over the long haul: genuineness, respect, and empathy.[5]

For those who are visually oriented, the relationship looks like this:

In efforts to apply these qualities, they appear as a blend, an overlapping; the way we participate in society, in our family, in our social network, and in our workplace, however, all depend on applying these characteristics.

In efforts to apply these qualities, they appear as a blend, an overlapping; the way we participate in society, in our family, in our social network, and in our workplace, however, all depend on applying these characteristics.

To make clear the meaning of these words, we cite some approximate equivalents:

| Our Term | Approximate Equivalents |

| Genuineness | Authenticity, Transparency, Openness |

| Respect | Caring, Agape Love |

| Empathy | Understanding, Feeling With |

Moving on to Part II, we will examine the art of listening as a starting point for our journey through the forest and trees of effective communication, with a regular circling back to those three essential attitudes of genuineness, respect, and empathy. Listening represents one of the three learnable skills supporting the three attitudes.

Listening According to the Harvard Business Review

Thoughtful managers, executives, and professionals have long been exposed to information about the importance of effective listening for the well-being of a group, unit, or organization. For example, the Harvard Business Review (HBR), that premier of all business journals, published back in 1957 an article titled “Listening to People,” by Ralph G. Nichols and Leonard A. Stevens.[6] “The effectiveness of the spoken word,” said Nichols and Stevens, “hinges not so much on how people talk but mostly how they listen.” In this HBR article, a top executive comments that perhaps 80% of his work depended on his listening to someone or someone listening to him. Is it very much different for those in the legal profession? I don’t think so. Lawyers daily speak and listen to co-workers, witnesses, opposing counsel, court officials, law enforcement—as well as spouse and kids.

When thinking about communication within a law firm, business, or a non-profit, these underlying axioms emerge[7]:

- For the effective functioning of any organization, communication stands as the premier process for tying together the units of an organization.

- This communication depends more on conversations than on written materials. (Again, concerning a law firm, I am speaking of the process of managing a law firm as distinguished from the practice of law.)

- Concerning conversation, the process depends much more on how people listen than how they talk.

Following are some well-researched truths about listening that demonstrate why, over fifty years after the HBR article was published, our listening doesn’t seem much improved[8]:

- Generally, people do not know how to listen.

- They have not been exposed to training concerning necessary listening skills.

- The average listener forgets one-third to one-half within eight hours and 75% after two months. (Why do so many listeners not take notes?)

Why Can’t People Listen Better?

Actually, paying attention while listening is a greater problem than most people believe. A factor exists in the listening process that most people are not aware of.

The real problem is this: We talk at a much slower rate than we listen. For most Americans, the average rate of speech is around 125 words per minute. While experts are not in full agreement, it’s generally agreed that people can listen at a speed far exceeding 125 words per minute. This average rate of listening is probably in the range of three to four times faster than the rate of speaking. Poor use of this time differential explains why people become so easily distracted when listening to another person.[9]

What are some of the better techniques for how we use this spare thinking time? Our two business professors writing in the HBR in 1957 suggest there are at least four processes we can use during this slack time[10]:

- The listener thinks ahead of the talker, trying to anticipate what the oral discourse is leading to and what conclusions will be drawn from the words spoken at the moment.

- The listener weighs the evidence used by the talker to support the points that he makes. “Is this evidence valid?” the listener asks himself. “Is it the complete evidence?”

- Periodically the listener reviews and mentally summarizes the points of the talk completed thus far.

- Throughout the talk, the listener “listens between the lines” in search of meaning that is not necessarily put into spoken words. He pays attention to nonverbal communication (facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice) to see if it adds meaning to the spoken words. He asks himself, “Is the talker purposely skirting some area of the subject? Why is he doing so?”

A web site dedicated to various communication topics directs our attention to the ways listening can go wrong. The author comments: “Most of us are terrible listeners. We’re such poor listeners, in fact, that we don’t know how much we’re missing.”

Following are some of the author’s factors that cause interactions to go bad for a listener and speaker and summaries of the antidotes:

| Factors That Cause Listening to Go Bad | Antidotes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other barriers to effective listening prevail, and I suggest the reader go to http://www.sklatch.net/thoughtlets/listen.html for an expansion on this topic.

High school and college students typically receive training in speaking and writing, but seldom in listening. Yet, as we have seen, more depends on listening than on speaking in our life’s work. The listener arguably bears more responsibility than the speaker for the quality of communication. For a long-term solution, students should experience aural incidents and role-playing that allow for discussion and skill improvement.[11]

Listening With Your Body as Well as Your Ears

Above, we described ways in which the listener could take up the slack time and productively think about elements of the situation that will move conversation forward. As an example, we noted that the listener can review and mentally summarize the points of the talk. There is, however, another practice which not only takes up the slack time but will encourage the speaker to be more forthcoming. This additional approach calls for using body language effectively. If the speaker is looking at the listener, and if the listener presents a blank stare with no bodily movement, this behavior will create a chilling effect for the speaker. Let’s see how the listener can communicate interest and concern for the speaker.

The listener can use the following body language to show interest and concern[12]:

- Move toward the speaker. This movement will say to the speaker that the listener is carrying out active listening, is concerned about the message, and cares for the speaker.

- Lean forward. Leaning back demonstrates lack of interest, while leaning forward tells the speaker that the listener is paying attention, is thoroughly connected to the speaker and the speaker’s message.

- Keep arms uncrossed. Crossed arms telegraph a lack of interest, while an open body position tells the speaker that the conversation is desired and of interest.

- Make eye contact. Nothing that the listener can do is more insulting, more disrespecting, than to look about the room, or worse, look at his or her watch. One can’t just stare at the speaker, but one can keep one’s eyes somewhere in the vicinity of the speaker’s face.

- Smile when appropriate. Nothing communicates interest and concern more than a smile at an appropriate juncture.

- Make sounds and facial responses. The listener can nod, say “uh huh,” “I understand,” “that’s interesting,” and the like, all showing that the listener is absorbed.

- Touch the person. A tap on the hand or arm, or similar non-invasive touching, communicates warmth and empathy. (Yes, men can hug.)

The literature on body language is vast; it describes many more body language movements than can be covered herein. At the end of the fourth blog, a bibliography will be provided.

In our next blog, we will examine leadership and its connection to communication, particularly public speaking.

“The difference between mere management and leadership is communication.”

—Winston Churchill

© Claude L. Kordus, 2010. All rights reserved.

[1] Jesse Vickey, Andy Ferguson, and Nicole Vickey, Life After School Explained (Palm Beach Gardens, FL: Cap & Compass, LLC, 2006) 15.

[2] Law Practice, May/June 2010:1, 61.

[3] Robert Bolton, Ph.D., People Sills (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986) 259.

[4] Tom Butler-Bowdon, 50 Psychology Classics (London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2007) 32.

[5] Bolton, 263.

[6] Ralph G. Nichols and Leonard A. Stevens, “Listening to People,” Harvard Business Review on Effective Communication (Boston: HBS Press, 1999) 1.

[7] Nichols and Stevens, 13, 14.

[8] Nichols and Stevens, 3, 4.

[9] Nichols and Stevens, 6, 7.

[10] Nichols and Stevens, 9.

[11] Nichols and Stevens, 19-23. These steps for an adult training program are easily adaptable to any high school, college, or graduate program.

[12] Matthew McKay, Ph.D., Martha Davis, Ph.D., and Patrick Fanning, How to Communicate: Second Edition (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, c. 1995) 183, 184.

This is an excellent article on a subject so critical to effective leadership. Nicely done, and it really gives the reader key takeaways they can use. I love that, because as a Leadership Coach, I have found it is key that clients have something concrete that they can turn into action.

Jayne