Let us review where we have been. In Part I, we asked the question: What causes people to be successful in their careers? I stated that I believe that understanding and developing “soft side skills,” and not just technical skills, will provide the best opportunities for a successful career. We reviewed evidence from leading universities that much more than half of job success comes from people skills. Many people who pursue a professional career think of their “work” as their technical expertise, but as one moves up in an organization, it becomes clear that dealing with people is of at least equal significance.

Communication as a Premier People Skill

We also noted that much of what we call people skills is really effective communication. We demonstrated how communication thinking and communication skills drive success in the legal field as well as business.[1]

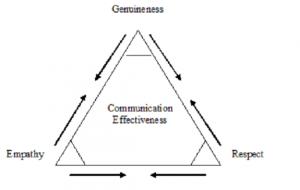

We used the model developed by Robert Bolton in People Skills: How to Assert Yourself, Listen to Others, and Resolve Conflicts to show that certain attitudes support a person’s successful efforts at effective communication, attitudes that produce good relationships before formal communication even starts. These attitudes are genuineness, respect, and empathy.[2] We will refer to this paradigm model.

The following is a visualization of Bolton’s model:

In efforts to apply these qualities, they appear as a blend, an overlapping; the way we participate in society, in our family, in our social network, and in our workplace, however, all depend on applying these characteristics.

In efforts to apply these qualities, they appear as a blend, an overlapping; the way we participate in society, in our family, in our social network, and in our workplace, however, all depend on applying these characteristics.

To make clear the meaning of these words, we cite some approximate equivalents:

| Our Term | Approximate Equivalents |

| Genuineness | Authenticity, Transparency, Openness |

| Respect | Caring, Agape Love |

| Empathy | Understanding, Feeling With |

Moving on to Part II, we examined the art of listening as a starting point for our journey through the forest and trees of effective communication, with a regular circling back to those three essential attitudes of genuineness, respect, and empathy. Listening represents a learnable skill supporting the three attitudes.

Listening According to the Harvard Business Review

We pointed out that, as far back as 1957, business journals like the Harvard Business Review (HBR), the premier of all business journals, were presenting information about the importance of effective listening. Nichols and Stevens stated that “[t]he effectiveness of the spoken word hinges not so much on how people talk but mostly how they listen.”[3] Fifty years later, it doesn’t seem that our listening has improved very much.[4]

- Generally, people do not know how to listen.

- They have not been exposed to training concerning necessary listening skills.

- The average listener forgets one-third to one-half within eight hours and 75% after two months. (Why do so many listeners not take notes?)

Why Can’t People Listen Better?

Because of its importance, we quote fully our comments from Part II of our blog about the difficulty people have in listening:

Actually, paying attention while listening is a greater problem than most people believe. A factor exists in the listening process that most people are not aware of.

The real problem is this: We talk at a much slower rate than we listen. For most Americans, the average rate of speech is around 125 to 135 words per minute. While experts are not in full agreement, it’s generally thought that people can listen at a speed far exceeding 125 words per minute. This average rate of listening is probably in the range of three to four times faster than the rate of speaking. Poor use of this time differential explains why people become so easily distracted when listening to another person.[5]

What are some of the better techniques for how we use this spare thinking time? Our two business professors writing in the HBR in 1957 suggest there are at least four processes we can use during this slack time.[6]

- The listener thinks ahead of the talker, trying to anticipate what the oral discourse is leading to and what conclusions will be drawn from the words spoken at the moment.

- The listener weighs the evidence used by the talker to support the points that he makes. “Is this evidence valid?” the listener asks himself. “Is it the complete evidence?”

- Periodically the listener reviews and mentally summarizes the points of the talk completed thus far.

- Throughout the talk, the listener “listens between the lines” in search of meaning that is not necessarily put into spoken words. He or she pays attention to nonverbal communication (facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice) to see if it adds meaning to the spoken words. He asks himself, “Is the talker purposely skirting some area of the subject? Why is he doing so?”

Further Evidence for the Importance of Relationship Building Through Appropriate Attitudes and Effective Listening

The writer thinks that my readers might be thinking that these ideas about attitudes and active listening may be just the musings of academics making more than is justified from available research. Let me show two additional sources of information that I believe will settle the question concerning the importance of attitudes and active listening.

Let’s look once more at the issue of developing and expressing the right attitudes to create the basis for collaboration and communication. I have long admired the book titled Primal Leadership by Daniel Goleman, also Richard Boyatzis and Annie McKee. Earlier, Daniel Goleman wrote the book Emotional Intelligence, a many-month number 1 bestseller. Drawing on extensive science and behavioral research, Goleman showed the factors at work when people of high IQ flounder and those of modest IQ do surprisingly well. To get our arms around this idea of social intelligence, we can look to Goleman’s description of men and women of high emotional intelligence:

[M]en who are high in emotional intelligence are socially poised, outgoing and cheerful, not prone to fearfulness or worried rumination. They have a notable capacity for commitment to people or causes, for taking responsibility, and for having an ethical outlook; they are sympathetic and caring in their relationships. Their emotional life is rich, but appropriate; they are comfortable with themselves, others, and the social universe they live in.

. . . Emotionally intelligent women tend to be assertive and express their feelings directly, and to feel positive about themselves; life holds meaning for them. Like the men, they are outgoing and gregarious, and express their feelings appropriately (rather than, say, in outbursts they later regret); they adapt well to stress. Their social poise lets them easily reach out to new people; they are comfortable enough with themselves to be playful, spontaneous, and open to sensual experience. Unlike the women purely high in IQ, they rarely feel anxious or guilty, or sink into rumination.[7]

Of course, these portraits are extreme; all of us are a mixture of IQ and EQ, but do notice the similarities between Goleman’s model and Bolton’s model.

In Primal Leadership, the authors explore the role of emotional intelligence in leadership. Under the heading of “Emotional Intelligence Domains and Associated Competencies” in Primal Leadership, we find, among others, these competencies leading to leadership[8]:

- Transparency: Displaying honesty and integrity; trustworthiness

- Developing others: Bolstering others’ abilities through feedback and guidance

- Empathy: Sensing others’ emotions, understanding their perspective, and taking active interest in their concerns

So here we have one of the leading current experts regarding organization effectiveness putting forth as avenues for reaching the goal of leadership the same three attitudes that Bolton described as the key to unlocking the door of collaboration some fifteen years earlier (the Bolton model).

Let’s look at another support for the things we have been saying about communication: in this case, it’s the importance of active listening. To reinforce the importance of active listening, we turn to Malcolm Gladwell, the author of the bestseller The Tipping Point, the book that caused readers to think differently about how movements jumped ahead at a particular strategic point in their history. For our purposes, we are drawn to his second bestseller, Blink, about how we think without thinking, sometimes successfully and sometimes not.

A section titled, “Listening to Doctors” provides an answer to this question: How important is active listening for professionals, in this case, doctors? Gladwell asks us to imagine that we are working for an insurance company that wants to find out which doctors are most likely to be sued. You can choose from two options for your research: the first involves examining the credentials of the doctors studied and determining how many errors they made; the second method involves listening to brief portions of conversations between each doctor and his or her patients.

I am sure lawyers are interested in the answer, and that answer is surprising. The probability of being sued has very little to do with how many mistakes a doctor makes, or for that matter, what his or her credentials are. Certain highly trained and skilled doctors get sued a lot, and certain other doctors who actually make a lot of mistakes never get sued. Also, most people who are injured due to the negligence of a doctor never sue. What’s going on here?

A leading malpractice lawyer told this story:

[I] had a client who had a breast tumor that wasn’t spotted until it had metastasized, and she wanted to sue her internist for the delayed diagnosis. In fact, it was her radiologist who was potentially at fault. But the client was adamant. She wanted to sue the internist. “In our first meeting, she told me she hated this doctor because she never took the time to talk to her and never asked about her other symptoms,”…. “‘She never looked at me as a whole person,’ the patient told us…. When a patient has a bad medical result, the doctor has to take the time to explain what happened, and to answer the patient’s questions — to treat him [or her] like a human being. The doctors who don’t are the ones who get sued.” It isn’t necessary, then, to know much about how a surgeon operates in order to know his likelihood of being sued. What you need to understand is the relationship between that doctor and his patients.[9]

Further research showed the surgeons who had never been sued spent more than three minutes longer with a patient each visit than those who had been sued at least twice. Those who had not been sued generally made comments about what the doctor was going to do in the visits and generally tried to make sure that the patient understood the process and tried to make sure that the patient was as comfortable as possible.

So here we have strong evidence that maintaining the right attitudes and maintaining a listening stance leads to more productive communication, something that has to be of great importance to the lawyer, the doctor, the business person, the nonprofit executive, the government supervisor, and anyone else who depends on language for moving forward toward their goals and objectives, which is just about everyone.

The Challenge of Public Speaking

For many, public speaking is a challenge—in fact, worse than a challenge. I have seen people get so sick before a scheduled speech that they could not go to the stage. I have seen people forget their speech and retreat from the podium. I have heard of at least one person who stepped up to the podium and died of a heart attack.

Undoubtedly, most people see public speaking as a problem rather than a solution, a threat rather than an opportunity, a bag of wet kittens rather than a cuddly puppy. Some have estimated that only 10% of managers and professionals see public speaking as a way to improve their careers.

Yet public speaking does provide great opportunities—a demonstration of social intelligence. Here are the reasons why:

- Most people are willing to follow the articulate.

- Most people lack the ideas and lack the skills for effective speech-making — which is usually persuasion, that is, getting done what the speaker wants doing.

- As we have said several times in these blogs, most people believe that if they perform their job description well, they will prosper. The current competitive world for good positions, apparently as severe in the legal profession as in other occupations, has smashed this delusion.

My own work experience spanning the law, business, and non-profits tells me that, overwhelmingly, those who progress faster and move higher have one capability in common; they are better communicators than their less successful brethren.

This problem is more severe for lawyers: The world expects lawyers to be accomplished public speakers. It’s the burden law graduates carry.

This blog is not going to miraculously convert the tyro into a tribune, but we can make some suggestions:

- There exists a variety of excellent texts, how-to books, and web sites on public speaking, or, as it is often called today, “presenting;” so, learn everything you can.

- Seek out opportunities to do public speaking: Aristotle said that the best way to do something is to do it.

- Find a willing and able coach.

As regards 3, I can’t coach any individual who might read this blog, but I can present some theories and action items that the reader might find useful, although I must warn the reader that these items may not be the most important, and certainly they are not complete.

Some Steps on the Road to Public Speaking Success

Since before the time of Aristotle, humans have been seeking an answer to the question: How can I be a better speaker? And a flood of books on how to be an exceptional speaker flow out of publishing houses each year. Why? Because so few people who read these books become exceptional speakers.

What the readers of these books don’t understand is that 1) answering their fears requires a great deal of self-appraisal and ego-deflating introspection, 2) getting it right is a long road with a lot of mediocre attempts on the way, and 3) many of the texts and self-help books miss some of the most important particulars. With trepidation, following I set forth some heuristics about public speaking that hopefully will fill in the gaps.

Don’t Do Dumb Things

Great speakers connect with their listeners. They show the attitudes described by the Bolton model: Genuineness and openness, respect and caring, and empathy and “feeling with.”

If you fail to show these kinds of qualities by word, gesture, facial expression, tone of voice, and attitude, you are in trouble. Don’t forget that the average adult has an individual attention span of about 15 to 30 seconds.

So, here are some certain ways to get your audience to tune out:

- Talk a lot about yourself

- Forget eye contact

- Frown

- Read your entire speech

- Use ironic, bitter humor

Know Your Audience

Don’t take a speech assignment if you don’t have time to do audience research. You might find yourself talking about Absolute Vodka’s clever advertising campaign to a group with a significant number of religious abstainers. (I actually witnessed this debacle. I know most lawyers would not get into this kind of subject matter, but you get the point.) Here are questions to ask[10]:

- Who will be in attendance? How many? Get a list of names, titles, roles and responsibilities.

- If it’s a decision-making meeting, will the decision-maker be in the room? Will the decision maker be there for the entire presentation or part of the presentation? What might cause [him or] her to miss it or leave before it is over?

- What [are the audience’s] expectations? What needs to be done to meet…expectations?

- What is the meeting theme?

- What agenda items come before and after your remarks?

- What is the expected attire? Is it formal, business, business casual or casual. [sic] When asking about attire, be sure to find out as much as you can. Business casual can mean different things to different groups. Casual to some is wool slacks, jackets and ties.

- Do the attendees get along? Do they laugh easily?

- What do the attendees have in common?

- How is the information you are going to cover relevant to the attendees?

- How might the information help the attendees?

- What are the starting and ending times for the meeting?

- What is the seating arrangement and can it be changed?

- Is it a neutral, friendly or hostile audience?

- What do they know about your topic?

- What do they know about you, the presenter?

(This list comes from Timothy J. Koegel, The Exceptional Presenter. In the bibliography at the end of these blogs, the reader will find helpful texts; Koegel, however, provides a large amount of useful information in a quick-read format.)

About accumulating information about people, organizations, and subjects: marketing brochures, web sites, internet search engines, periodicals, industry and local business journals.

Set Your Desired Tone

Tone is a difficult concept. What is it precisely? Is it attitudes, such as the Bolton model? Is it the emotional tenor of the speaker? Is it the general direction or drift of thought? Is it an extension for the speech’s subject?

One expert has suggested that tone presents itself through two dimensions:

- positive/negative

- formal/informal

We can control the tone through the words we use:

| Negative | The office will close at 7 p.m. |

| Positive | The office will remain open until 7 p.m. |

| Formal | No pronouns/no contractions |

| Informal | Pronouns/contractions |

Tell Stories

Telling a story that is appropriate to a speech’s theme can be powerful. Stories work particularly in the introduction and conclusion of a speech; they work well because everyone enjoys stories, especially if they follow some rules of thumb:

- Story is relevant to the main point of the speech

- Story is told with conviction

- Story is short (long stories can be deadly)

- Story incorporates some humor

- Story is personal (not necessary, but helpful)

As an example, picture a legislator who believes that the new federal medical system is wrong for the country telling this story:

Before our Constitution in the 1780s, the United States was floundering in debt. One day during this period, Franklin entertained Dr. Benjamin Rush and Thomas Jefferson. The conversation turned to determining what was the oldest profession.

Dr. Rush, a physician, said the oldest profession was his. “After all, it was a surgical operation that made Eve out of Adam’s rib.”

But Jefferson, who built Monticello, said, “No, it was the architect. Surely it was an architect who brought the world out of chaos.”

Then Franklin replied “You re both wrong. It’s the politician. After all, who do you think created the chaos?”[12]

I believe we would say the story was relevant, certainly told with conviction, short, and incorporates humor.

Here is one more example:

Suppose you are speaking on the topic of leadership: “Willie Shoemaker, one of horse racing’s greatest jockeys, once said, ‘I always tried to keep the lightest possible grip on the horse’s reins. The horse never knows I’m there until he needs me.’”

Observe the Rule of Three

The rule of three provides one added feature to a speech, expressing ideas more completely, emphasizing structural points, and increasing the memorability. What is the rule of three? What are some famous examples? How do you use it in speeches?

Trios, triplets, and triads abound in Western culture in many disciplines. Just a small sampling of memorable cultural triads includes:

- Christianity

- Father, Son, and Holy Spirit

- Heaven, hell, and purgatory

- Three Wise Men with their gold, frankincense, and myrrh

- Movies & Books

- The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

- Sex, Lies, and Videotape

- Superman’s “Truth, Justice, and the American Way”

- Nursery rhymes such as the Three Little Pigs or Goldilocks and the Three Bears

- In a more general sense, there is the allure of trilogies as with Indiana Jones, The Godfather, The Matrix, Star Wars, and many others.

- Politics

- U.S. Branches of Government: Executive, Judicial, and Legislative

- U.S. Declaration of Independence: “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”

- French motto: Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité

- Abundance of tri-colored flags

- Civic, Organizational, and Societal Mottos

- Fire safety motto: Stop, Drop, and Roll

- Olympic motto: Citius, Altius, Fortius or Faster, Higher, Stronger

- Real estate: Location, Location, Location

- History

- Julius Caesar:“Veni, vidi, vici” (I came, I saw, I conquered)

- Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: “Friends, Romans, Countrymen. Lend me your ears.”

- Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address:

“We can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground.”

“Government of the people, by the people, for the people” - General MacArthur, West Point Address, 1962: “Duty, Honor, Country” [repeated several times in the speech]

- Barack Obama, Inaugural Speech: “[W]e must pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and begin again the work of remaking America.”

Why does the rule of three work? Experts are not sure. A triad does give one a sense of completeness, closure—besides that, it’s magic.

[The examples for is section were taken from http://sixminutes.dlugan.com, an exceptional site for speech-making ideas and examples.]

30 Speechmaking Tips

- Start with a structure.

- Incorporate material to support one theme only or one objective.

- Think of this structure as a design for all speeches:

1. Tell them what you’re going to tell them (opening).

2. Tell them (body).

3. Tell them what you just told them (close). - Keep speech short. (After 18 minutes, people mentally drift away.)

- Keep sentences short.

- Use active voice.

- Use powerful verbs. (not “eliminate,” but “crush”)

- Constantly reengage through the use of many kinds of materials: facts, stories, quotes, statistics, poems, history, examples, anecdotes.

- Deliver with passion.

- Repeat theme or objective throughout speech.

- Use positive language:

No: “She is not efficient.”

Yes: “She is inefficient.” - Provide internal summaries and definite transitions.

- Use eye contact.

- Don’t read speech.

- Always prepare for question and answer; even if not planned for, they often occur.

- Use pauses—they can be used as transitions and the audience can get a brain rest.

- Avoid PowerPoint if at all possible; the speaker disappears with PowerPoint.

- Use good posture and appropriate body language. Deliver speech to a friend or friendly group before actual speech; get feedback.

- Assure that all visuals have a purpose.

- Genuinely smile and let face express your feelings.

- Read about body language. (See, for example, Koegel, Chapter Five.)

- Avoid verbal graffitti: “Um,” “you know,” “to be honest with you.”

- Avoid long words, unusual words, and jargon.

- Personalize your remarks as much as possible.

- Share your eye contact with entire room.

- Move toward the audience as often and as far as possible.

- Use humor as often as possible. (Prefer situational humor over jokes.)

- Look up as much as possible, not down.

- Respect the “Rule of Three.”

- Keep throat loose.

- Use voice variety to match meaning: pitch, rate, volume.

- Vary tonality, the voice’s personality: smooth/harsh, etc.

- Practice, practice, practice.

What Causes People to Be Successful in Their Career? Take Aristotle with You to Every Meeting

By meeting, I mean every interaction with others, whether one on one, small group, formal decision-making, presentation, or large-group public speech. Our examples for this blog come primarily from oral communication, but the suggestions often apply also to written communication. The concept for communication determining clear success goes back a long way, some 2,300 years, all the way back to Aristotle (384-322 BCE). He stands with the greatest philosophers of all time. Judged by intellectual and Western cultural influence, only Plato, his teacher, can be thought of as a peer, and yet he taught the sons of affluent Athenians how to hold their own verbally in the assembly, the courts, and on the public podium.

Aristotle researched, taught, and wrote about every subject known to the Western world at that time: One of his best known works and still widely used today is his On Rhetoric. This work influenced great speakers of the ancient world such as Cicero and Quintillian and also influenced great speakers right down to our era, including Winston Churchill. Since at least five separate editions exist in English, the continuing influence of On Rhetoric is apparent.

The modern reader of Aristotle’s On Rhetoric, the first comprehensive text on the art of persuasion, oral and written, will find this work a challenge: many allusions to contemporary affairs, a dry and sometimes complex style, and unfamiliar language all create difficulty. Granted this difficulty, most of the subjects one would expect are covered: voice, gestures, style (with special emphasis on clarity), metaphor, story, speech structure, appeals to reason, feelings, and speaker credibility, speech venues: the court room, the assembly, and the forum, all of these and more are covered.

For our purposes, we will cover here only Ethos, Pathos, and Logos: the three pillars of persuasion. What do these words mean? As we have stated earlier:

- Ethos: credibility and character of the speaker

- Pathos: the emotions of the audience created by the speaker

- Logos: logical argument, but in the sense of practical reasoning, and not formal philosophical logic

Aristotle has been called the philosopher of common sense and the great empiricist. He observed much speaking and debate in Athens—it was a robust oral society with some elements of what we would call democracy—only some elements: slavery was common and women experienced a much diminished role versus men. With that said, the citizens of Athens bargained, discussed, debated, and carried on public speaking tasks expected of citizens.

How does this work relate to our current endeavor? Consider this model:

| Aristotle | Current Blog |

|

|

Thus we have tied together the various threads from the three blogs. From the beginning of these July blogs, the underlying theme has been: What causes people to be successful in their careers? The simple answer is “soft side skills” or “people skills.” The more complex answer is for a person to be perceived as successful in his or her life vocation, in order to be seen as a high performer, and yes, to be seen as a leader—high communication skills are required. We noted that Garth Saloner, dean of the Stanford Graduate School of Business, observed:

[T]he ability to work effectively with and through people is one of the most important determinants of success in any organization. Self-awareness, knowledge of the impact of one’s style on others, and skill at interpersonal interactions are at least as important a part of the leader’s skill set as is training in the more traditional business disciplines.[13]

This observation applies whether one exists within a law firm, a business, a government agency, or a non-profit. Leadership in Aristotle’s time required a command of communication tools, and so it does today:

To awaken vitality in others…leaders have to cross a certain boundary between themselves and their associates. Sometimes it’s not easy, because most of us have been raised to believe that it’s important to maintain a buffer of “safety and good sense” between ourselves and the people who choose to follow our leadership. Perhaps the greatest risk we take as leaders is losing the interpersonal safety zone. If we don’t open up to others and express our affection and appreciation, then we stay safe behind the wall of rationality …[I]t’s not an either-or. We have minds and hearts. Both are meant to be used at work. When we use them both, we’re more effective. To use our minds and not our hearts is to deny ourselves greater success.[14]

Thus, take Aristotle to your next meeting.

Note: The next and last blog will cover language: word choice, style, and language sophistication.

© Claude L. Kordus, 2010. All rights reserved.

[1] Law Practice, May/June 2010:1, 61.

[2] Robert Bolton, Ph.D., People Skills: How to Assert Yourself, Listen to Others, and Resolve Conflicts (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986) 259.

[3] Ralph G. Nichols and Leonard A. Stevens, “Listening to People,” Harvard Business Review on Effective Communication (Boston: HBS Press, 1999) 1.

[4] Nichols and Stevens, 3, 4.

[5] Nichols and Stevens, 6, 7.

[6] Nichols and Stevens, 9.

[7] Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence (Bantam,) 45.

[8] Daniel Goleman, Richard Boyatzis, and Annie McKee, Primal Leadership: Learning to Lead with Emotional Intelligence (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004) 39.

[9] Malcolm Gladwell, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (New York: Back Bay Books, 2007) 41.

[10] Timothy J. Koegel, The Exceptional Presenter: A Proven Formula to Open Up! and Own the Room (Austin, Texas: Greenleaf Book Group Press, c. 2007) 127.

[11] Brandon Royal, The Little Red Writing Book (New York: Metro Books, 2009) 84.

[12] James C. Humes, Speak Like Churchill, Stand Like Lincoln: 21 Powerful Secrets of History’s Greatest Speakers (New York: Three Rivers Press, c. 2002) 74.

[13] Garth Saloner, Stanford Business, Summer 2010: 5.

[14] James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner, Encouraging the Heart: A Leader’s Guide to Rewarding and Recognizing Others, first edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, c. 1999) 12.

Thanks for the great article.

Excellent article.