By June 1863, the Confederates had won some major victories at Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg, although they paid a heavy price with the loss of the legendary Stonewall Jackson. Tragically, he was killed by some jumpy Confederate pickets who had mistaken him and his troops for Northerners.

By June 1863, the Confederates had won some major victories at Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg, although they paid a heavy price with the loss of the legendary Stonewall Jackson. Tragically, he was killed by some jumpy Confederate pickets who had mistaken him and his troops for Northerners.

Lee wanted to seize the momentum by moving into Northern territory through Maryland and Pennsylvania. His hope was to catch the Union army off guard and also to move the war away from the impoverished fields of Virginia and other parts of the South and take advantage of the fertile fields and plentiful livestock in Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Stonewall Jackson’s old 2nd Corps., now under the command of General Richard Ewell, who had lost a leg at Second Bull Run, marched into Pennsylvania headed toward Carlisle, while another army under the command of Major General Jubal Early, marched toward York and Harrisburg, which was the railroad center for the North. The Confederate Army continued to push North into Pennsylvania, using livestock, food, wagons, and clothing taken from Pennsylvania civilians (with a promise to pay them Confederate money once the war was won).

There was no thought of engaging in battle in Gettysburg, but rather one of the greatest battles ever fought on American soil began as a routine mission to obtain shoes.

The Confederate soldiers had not only been deprived of food, shelter and clothing, but also were in dire need of shoes, to the point where some of the men were marching barefoot over rocky terrain — they had lots of heart, but not much sole! There were reports of a large cache of shoes available in the little town of Gettysburg and some of General Ewell’s infantry set off to confiscate them.

The Confederates had no sense that there was any Union army in the area, but only reports of scattered militia. The reports were wrong. A Union cavalry under the command of General John Buford was actually about three miles from Gettysburg and an advance group of Confederate skirmishers ran head-first into them.

Neither side wanted to engage in battle since both felt they were undermanned and ill-equipped to engage in prolonged combat. Nevertheless, shots were fired and the battle was on. Both sides dispatched couriers in all directions to obtain reinforcements while Buford attempted to hold his position.

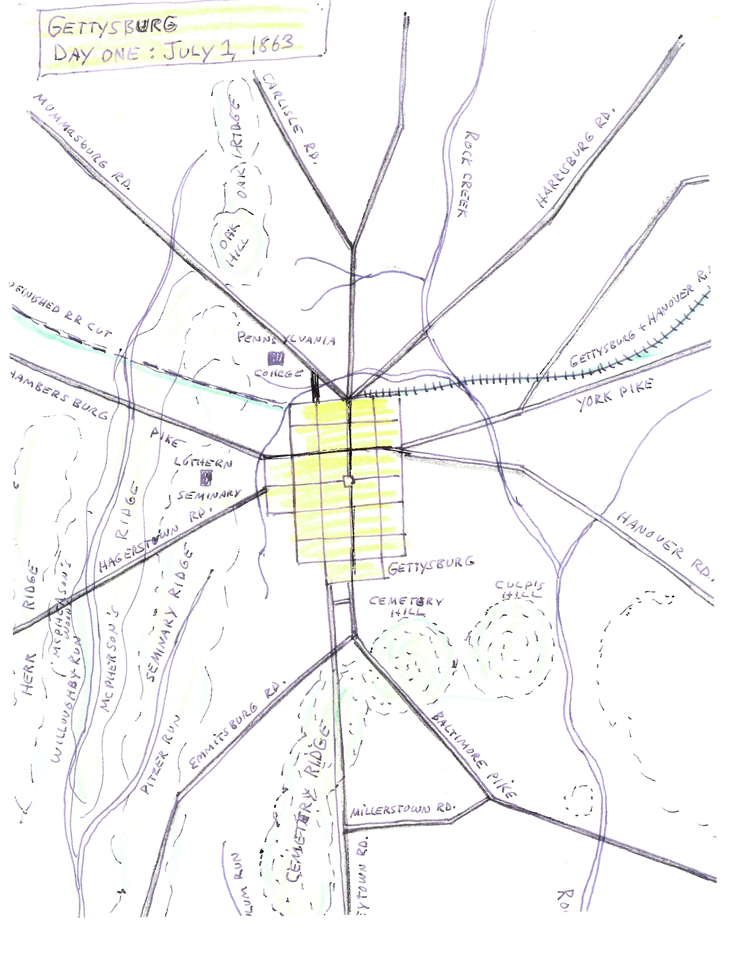

Confederate troops from Alabama advanced and the main battle opened on July 1, 1863, with Confederates attacking the Union troops on McPherson Ridge, west of town. Although they were heavily outnumbered, Union forces held their position, largely through the extraordinary bravery and intense fighting of the famous Iron Brigade comprised of, among others, the Wisconsin 2nd and 7th regiments, which suffered heavy casualties. They were able to hold their ground until they were finally overpowered and driven back to Cemetery Hill south of town. Their bravery is commemorated today by a monument along the wooded trails of McPherson Ridge. (A map of the Gettysburg battlefield prepared by local Civil War historian Professor John Angelos appears at the end of this post.)

By nightfall the main body of the Union Army, now commanded by newly appointed Major General George G. Meade, arrived on the scene and took up their positions. Meade must have been in a state of shock. He had been awakened about 4:00 am on June 28, (just 3 days before) and told of his appointment to lead the Union Army — a position he neither sought nor desired. But being a loyal West Point graduate, he felt it was his duty to follow orders from his Commander in Chief, however difficult and onerous the challenge.

By the second day of battle, July 2, 1863, both armies had fortified their positions and added substantially to their numbers. Armies continued to arrive from various directions throughout the night and by morning 65,000 Confederates massed against 85,000 Union troops. Confederates were considerably handicapped by the absence of the flamboyant General James Ewell Brown (JEB) Stuart, whose cavalry was regarded as Lee’s eyes and ears. He finally arrived on day two of the battle out far ahead of his 120 wagons and mounted cavalry, which lagged far behind. Lee was upset by his late arrival, but pressed him into battle nonetheless.

Fierce battles were fought at different positions throughout the day, with the main bodies of both armies only about a mile apart on parallel ridges. As battles reached close quarters, the advantage continued to go back and forth, neither army being able to seize control.

This monumental struggle with yet more heavy casualties suffered throughout the day of fierce fighting set the scene for the final day of battle on July 3, 1863, which many historians consider to be the decisive battle of the civil war. After much discussion and debate, General Lee made the decision to send some 12,000 Confederate infantry to break the Union lines and cross Cemetery Ridge. To do so, they had to traverse an area which, as I viewed it from Cemetery Ridge where the Union army waited, was a wide open field with virtually no protection of any kind. The resulting attack, later referred to as “Pickett’s Charge” was repulsed with casualties so enormous that Lee finally determined that he could not continue the battle and began to retreat back into Virginia.

The Gettysburg National Military Park maintains a Visitor Center which has a museum, video presentations, and a famous diorama highlighting the battlefields and the various battles that took place and much more. The park stretches across miles and miles of rolling hills in a scenic Pennsylvania countryside which has been carefully preserved and closely resembles the conditions as they were in 1863.

The Battle of Gettysburg was among the bloodiest in history. There were more than 51,000 casualties, 28,000 from the South and 23,000 from the North. When Lee began to withdraw his troops and retreat toward Virginia on July 4, Meade, whose troops had also suffered significant casualties, pursued, but at a distance. Both armies left behind a countryside and town ravaged by horrifically bloody and intense fighting at close quarters.

When the armies retreated, the townspeople (who numbered only about 2,800) were left to deal with more than 30,000 dead and wounded soldiers from both sides. The armies took most of their doctors and medicine with them, leaving burial and medical care to the townspeople. Despite the horrific casualties from both armies, the civilian population miraculously survived almost unscathed. There was only one civilian casualty, a young woman named Jennie Wade, who was killed by a stray bullet that went through two homes and struck her in the head as she stood holding an infant, who was not harmed.

The Battle of Gettysburg, which coincided with General Grant’s stunning victory in Vicksburg, Mississippi, spelled the beginning of the end for the Confederate cause. Nevertheless, the war continued on for more than a year and a half until Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, in April 1865.

The Gettysburg community was left in shambles after the battle, prompting Pennsylvania’s Governor, Andrew Curtin, to commission a local Gettysburg attorney, David Wills, to purchase land for a proper burial ground for Union dead. Within four months of the battle, the effort to bury the Union dead began on the 18 acres which became the Gettysburg National Cemetery.

The Cemetery was in its early stages by November 1863, when Abraham Lincoln arrived for its dedication. On November 19, 1863, Lincoln came there for dedication ceremonies. The principal speaker for this occasion was a famous orator named Edward Everett who delivered a well-received two-hour speech filled with historical detail and classical references. President Lincoln, who had been asked only to make a few “appropriate remarks” delivered a speech that contains just 272 words and took about two minutes to deliver, but became forever famous as “The Gettysburg Address.”

The cemetery, which stands just outside the center of the quaint town of Gettysburg, is open to the public. Walking around the graves of so many unknown soldiers, as well as the graves of so many heroes who have died in wars since the Civil War, and standing within a hundred yards or so of where Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg address was an unforgettable, almost spiritual experience.

The Battle of Gettysburg, like so many other battles and aspects of the Civil War, as well as trials and football games, created endless debates among Monday morning quarterbacks about strategies, decisions, and perceived mistakes — all with the great benefit of hindsight. Here is my view on a few of them:

1) The infamous and disastrous charge on July 3 is popularly referred to as “Pickett’s Charge.” Considering all the facts, this seems to me to be manifestly unfair. Major General George E. Pickett, was only one of three Confederate Generals to lead the charge, the others being Pettigrew and Trimble. He simply followed orders issued by General Lee who escapes unscathed and is consistently treated kindly by most historians. In fairness, this debacle should have been referred to as “Lee’s Charge,” which it probably would have if the South had won.

2) General James Longstreet vehemently objected to Lee’s order and correctly argued that to charge across wide-open fields would be suicidal. Longstreet gets criticized for having the temerity to challenge Lee, but if his view had prevailed a great slaughter could have been prevented and the outcome of the whole battle may have been different. There is a very small statute of Longstreet at Gettysburg, dwarfed by an enormous marble monument of Lee astride his famous horse.

3) A Union officer named Daniel Sickles was widely criticized for moving his troops out of position, which caused the left flank of the Union army to be weakened and exposed to a withering attack. But when walking the battlefield it is clear that Sickles had been positioned on a low, flat piece of ground where he was essentially a “sitting duck” for Confederate guns. The outcome of his move out of such a flat area caused many casualties, but the decision, based on the information he had available to him at the time, was not unreasonable.

Sickles is also notable for the fact that he was not a West Point graduate and had no previous military experience. Rather he was a U.S. Congressman who became a General through his political connections.

Sickles also gained notoriety in the legal profession by being among the first defendants to be acquitted of a first-degree murder charge based upon a defense of temporary insanity. The charges grew out of an incident in which an enraged Sickles shot and killed a man who had a love affair with his teenage bride. The victim was the son of the famous Francis Scott Key, who wrote our national anthem “The Star Spangled Banner.”

The clever theory of Sickles’ legal defense was that he acted “on an irresistible impulse” — the defense later popularized in the best-selling book and movie, “Anatomy of a Murder.” Paul Biegler (played by Jimmy Stewart), a small town lawyer from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, convinced a local jury that his client (played by Ben Gazzara) had killed a man who was alleged to have raped his wife (played by Lee Remick) while acting on an irresistible impulse that prevented him from knowing right from wrong.

4) History also seems to have done a considerable disservice to old George Meade, the newly-appointed head of the Union Army, who had only a few days to prepare for the Battle of Gettysburg. Meade was a solid military man with a strong West Point background, but he seems to be overshadowed by General Grant and also by General Lee, whom he defeated at Gettysburg, the definitive battle of the Civil War. He is criticized for not pursuing Lee as he retreated from Gettysburg, but in fact his own army had suffered huge casualties and was in no condition to either march or engage in combat. History confirms that he made the right decision.

Both Antietam and Gettysburg are a comfortable two-hour drive from Washington, D.C., and are well worth a visit. They are quiet and beautiful. The rolling countryside, reminiscent of Western Wisconsin, provides a beautiful, peaceful, and moving tribute to a major part of our Country’s cherished history.

Great article. I was awaiting the Civil War part 2 post and it sure did not disappoint!

Is there going to be a Civil War Sesquicentennial Part 3???