Grapes of Roth, Part II: A Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing

[This is the fourth in series of posts summarizing my new article, “The Grapes of Roth.”]

Introduction

Part I-A: Duck-Rabbits in Equity

Part I-B: Counting to 21 Similarities

By the mid-1970s judges in both the Second and Ninth Circuits realized that the “recognizability” standard for copyright infringement determinations was unworkable. As Roth Greeting Cards and International Luggage Registry had demonstrated, mere recognizability swept uncopyrightable as well as copyrightable material into the comparison, and hinged the infringement determination on the faintest suggestion of either. Some test was needed that would allow courts to do all three parts of the difficult balancing act described in Part I-A, in particular the assessment of how much protectable material was taken and whether that amount surpassed some threshold that made it unreasonable. Pre-Legal-Process courts had tackled these questions, but without saying much more than that the defendant had “wrongfully appropriated” the plaintiff’s protected expression, or taken its “aesthetic appeal,” or “justified” an infringement claim. Such openly normative assessments, relying on the judge’s subjective evaluation of the material taken, plainly would not do in a more formalist age. An alternative framework was needed.

Two decisions in rapid succession, one from the Second Circuit and one from the Ninth, latched onto the “total concept and feel” phrase as a way to express an overall level of similarity or dissimilarity in protected expression without openly making a normative or aesthetic judgement. In Reyher v. Children’s Television Workshop (2d Cir. 1976), the Second Circuit considered a claim by the authors of a children’s book based on a simple story: a lost child describes her mother only as “the most beautiful woman in the world,” which delays finding her because the mother does not meet conventional expectations of beauty. Sesame Street Magazine published a 2-page story that followed the same basic plot, but had different dialog, different illustrations, and was set in a different location. Was it infringing? Certainly the story was recognizable, but in almost every other detail the works were completely different. Reaching for a way to assess the protected expression in the stories holistically, the panel fell upon the empty verbiage from Roth: Given the simplicity of the stories, the court suggested, “we might [also] properly consider the ‘total concept and feel’ of the works in question.” Aside from a similar sequence of events, which the court found to be unprotectable scènes à faire, the remainder of the stories had an entirely different “total feel,” and thus there was no infringement.

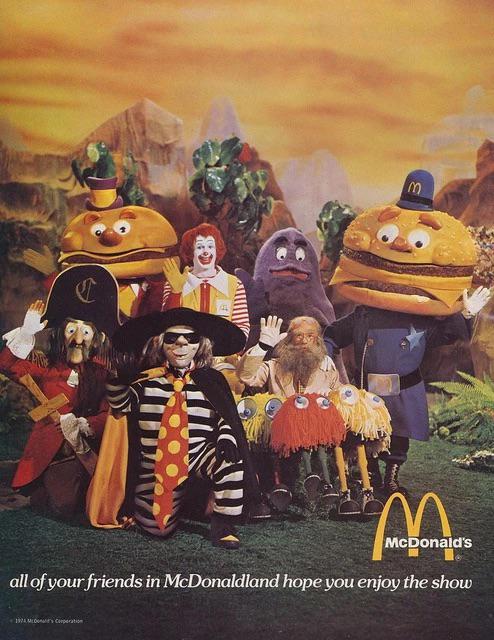

The following year, the Ninth Circuit found its way back to the Roth formulation as well. In Sid & Marty Krofft Television Productions, Inc. v. McDonald’s Corp., the plaintiffs claimed that their children’s television show, “H.R. Pufnstuff,” had been ripped off to make the McDonaldland characters — Grimace, the Hamburgler, Mayor McCheese, etc. The issues were whether the jury verdict of infringement was correct and whether damages had been properly determined. But the opinion started with a long discussion of the proper test for infringement, casting shade — without mentioning any names — on how it had been done up to that point. Merely asking about the similarity between two works — in other words, whether anything from the plaintiff’s work is recognizable in the defendant’s — produces “some untenable results,” the court noted. “Clearly the scope of copyright protection does not go this far. A limiting principle is needed,” namely one that separates out idea from expression and determines only the extent to which there has been copying of the latter.

The court then grandiosely declared, “The test for infringement therefore has been given a new dimension.” Unfortunately, as is well known, that new dimension was a thorough garbling of the Arnstein v. Porter decision from the Second Circuit, a misstep that has thrown Ninth Circuit caselaw for a loop it is still trying to recover from. But after mangling the concept of substantial similarity, the Ninth Circuit had to apply its new framework to the jury verdict below, which had held the McDonald’s characters to infringe the somewhat similar-looking H.R. Pufnstuf characters. Were they? The Ninth Circuit panel agreed with the jury. “It is clear to us that defendants’ works are substantially similar to plaintiffs’.” Why? “They have captured the ‘total concept and feel’ of the Pufnstuf show.”

In both Reyher and Sid & Marty Krofft, the reference to “total concept and feel” allowed the court to express a conclusion as to whether the defendants had taken too much copyrightable expression without specifically identifying what in the plaintiff’s work was expression, what in the defendant’s work was similar or dissimilar, and where the threshold level of similarity lay. “Total concept and feel” was thus a way of summing up all three of the difficult judgments an infringement determination required, and it did so in a way that met modern judicial norms while avoiding the ham-handedness of “recognizability.”