The recent revelation that Milwaukee Brewer all-star Ryan Braun has tested positive for performance enhancing drugs once again raises the question of why such revelations bother sports fans so much.

The recent revelation that Milwaukee Brewer all-star Ryan Braun has tested positive for performance enhancing drugs once again raises the question of why such revelations bother sports fans so much.

The answer lies, I believe, in the typical fan’s feelings about his or her lack of natural athletic ability. It is one of the sad facts of life that there is no correlation between love of, and enthusiasm for, sport and the possession of athletic ability. Consequently, the thought that some extraordinary event (or substance) might transform an average or below average athlete into a superstar performer is a very common fantasy, especially among males.

Over the years, this fantasy has generated its own literature. My three favorite versions are the 1949 movie, “It Happens Every Spring,” Douglas Wallop’s 1954 novel, The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant (which was the basis for the musical, “Damn Yankees”), and the 1962 comic book story, “Goliath of the Gridiron.”

“It Happens Every Spring” was written by Academy-Award-winning writer Valentine Davies who based the screenplay on a short story by University of Michigan administrator Shirley Smith (who despite his given name was male).

In the story, Vernon Simpson, a baseball-loving college chemistry professor at a small Midwestern college, accidentally produced, through a laboratory mishap, a liquid that makes anything it touches repellant to wood. Simpson immediately realizes that a baseball coated with this liquid could not be hit with a wooden bat. Thus, a pitcher who kept his glove moist with the strange substance would be able to throw unhittable pitch after unhittable pitch.

So inspired, Vernon abruptly resigns his teaching position and abandons his fiancé to travel to the ballpark of this favorite team, the St. Louis Cardinals. Although the season is already underway, Vernon worms his way into a tryout with the Cardinals, and when his manager realizes that he has found an unbeatable, if somewhat flaky, pitcher, he immediately signs him to a contract and inserts him into the starting rotation.

Calling himself simply “Kelly” to disguise his real identity, Vernon reels off thirty straight victories as he pitches the Cardinals into the World Series against the powerful New York Yankees. By Game 7, however, Vernon’s supply of his magic liquid is nearly gone, and he has no way of making any more of it. Even so, his teammates expect him to pitch the penultimate game of the season, so he has to take the mound as his real self. Miraculously, the Cardinals win the game 7-5 when Simpson, with the bases loaded in the 9th inning, snares a vicious line drive with his bare pitching hand to preserve the victory. His hand is badly broken, but that is really no misfortune since it gives him as excuse to retire from baseball without having to explain the sudden disappearance of his pitching ability.

Having had his moment of glory, Simpson decides to return to his previous life as a college teacher, if that is possible. When he arrives with great apprehension in the small college town that he abandoned several months earlier, he is welcomed back as a conquering hero by his former students and colleagues (and fiancé), all of whom had already figured out that the great Kelly was their own Vernon Simpson.

The viewer shares Vernon’s triumphs and notices hardly at all that our hero reached the pinnacle of the baseball world by blatantly cheating every time he applied his magic liquid to the baseball. In this world, at least, such sins can be forgiven.

In “The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant,” the magical transformation is not the result of a strange chemical substance, but a pact with the Devil himself. Melancholy and middle-aged, Joe Boyd is a married insurance salesman whose drab existence is made even more unbearable by the chronic failure of his beloved hometown baseball team, the Washington Senators.

In exchange for his soul, the Devil, now using the name Applegate, converts him into Joe Hardy from Hannibal, Missouri, who comes across like a combination of Li’l Abner and Babe Ruth, only more handsome and an even better ballplayer. Like Kelly, Hardy gets a tryout with his favorite major league team, and his obvious talent wins him a spot on the roster. His batting and fielding skills are unmatched, and the now inspired Senators begin the long process of catching the Yankees in the American League standings.

Boyd was not completely oblivious to the consequences of selling one’s soul to the Devil, and as a good insurance man, he manages to talk Applegate into accepting an “opt out” provision in the contract that he signs. On a specified date, not coincidentally set by Applegate for the day before the final game of the season, Boyd can cancel the deal without any further obligations. If Joe exercises the opt-out option, Joe Hardy will immediately turn back into old Joe Boyd, but Boyd will get his soul and his freedom back.

From the beginning Joe’s plan is to outsmart the Devil by playing so well that the Senators will have clinched the American League pennant before the opt-out date, at which time he can leave the team. This way, Joe will save his soul but still guarantee his home city and his favorite team a long-awaited championship. Boyd, of course, underestimates the Devil, who would never have agreed to a deal like the one Joe proposed, unless he was certain that Joe would not be able to exercise the clause.

As it turns out, the Senators play spectacularly well, winning game after game with Joe in the line-up. However, the Yankees, who may have a deal of their own with Applegate, do nearly as well, and with one game to go in the season, the Senators and Yankees are tied for first place. Naturally, the final game pits the Senators against the Yankees. Although he wants to return to his previous life, Joe realizes that he cannot let his teammates and his fellow Washingtonians down, so he accepts eternal damnation and lets the opt out date pass, just as Applegate knew he would.

Of course, the Devil is also a tremendous Yankee fan, and he had always intended to arrange another Yankee pennant, even while snaring Joe’s soul. Unfortunately for the Devil, Joe plays even better than Applegate thought possible, and the Senators lead the Bronx Bombers by one run going into the 9th inning with Applegate in the stands.

With two outs and the potential tying and winning runs on base, a Yankee batter hits a short fly ball between the infield and the outfield which seems destined to drop in for a double that will drive in the go-ahead run. However, from his centerfield position Joe summons up every bit of athletic energy that he possesses and lunges furiously for the ball. When it becomes obvious that he is going to catch the ball for the final out, the Devil, who loves the Yankees more than anything else in the universe, has no choice but to release Joe Boyd’s soul from captivity by changing Joe Hardy back into Joe Boyd.

Miraculously, the transformation of Joe Hardy back into Joe Boyd, with his 40-something-year-old insurance salesman body, does not prevent him from catching the ball. In one glorious moment, he beats the Devil at his own game, and in doing so, he preserves both his soul for all eternity and wins the pennant for the Senators. With the ball still in his glove he runs directly to the Senators dugout, where he sheds his uniform and slips back into his former humdrum life before his teammates and the reporters can catch up to him.

As with Vernon Simpson, the reader identifies with Joe’s dreams of athletic glory and breathes a sigh of relief when he narrowly escapes the fires of Hell. Little attention is paid to the question of whether it was really fair for a supernaturally enhanced being like Joe Hardy to play baseball with ordinary humans inhabiting ordinary, albeit athletically talented, bodies, or if a championship won under such circumstances really means very much.

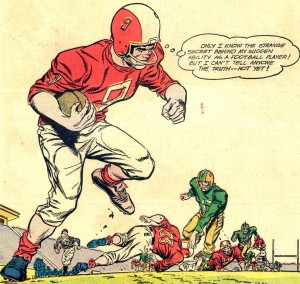

The final example is the comic book story, “Goliath of the Gridiron,” which first appeared in the Dec. 1962/Jan. 1963 edition of DC Comics’ The Brave and the Bold magazine. The story was part of the legendary “Strange Sports” series and was reprinted in comic book anthologies in 1968 and 1970. The story has, over the years, developed a cult following.

In the opening panels of the story, Jim Spencer is an outstanding botany and agricultural science student at Hartnell A&M University. His problem though is that he does not want to be a highly regarded young scientist, he wants to be a star running back on the college football team, which, incidentally, is coached by his father. However, unlike the star players that his female classmates swoon over, Jim has a scrawny build and no discernible athletic talent.

One evening, while looking in the forest for nutrient-rich potting soil, Jim comes upon a patch of eerily glowing dirt near where a meteorite had earlier landed. Jim digs up the soil, takes it back to his lab, and plants a number of berry-yielding plants in it. The next day, to Jim’s surprise, the plants have grown enormously and are already sprouting unusually large berries. Putting two and two together in the style of the scientist-adventurer of mid-20th century American popular culture, Jim realizes that if he eats some of the berries, they are likely to have a similar effect on his body.

Voila. The next morning Jim is a Charles Atlas look-alike, and though his parents hardly recognize him, Jim convinces his father to allow him to try out for the college football team. With his newfound speed and strength, Jim impresses his father so much that he is quickly inserted into the starting lineup. Although it obviously helps if your dad is the coach, his father’s confidence is quickly rewarded as Jim scores seven touchdowns in his first game.

Similar performances follow, and Jim is quickly the most popular man on campus and has attracted the attention of the gorgeous blonde, Betty Craks, the girl after whom he had long lusted. Other stellar performances follow, but Jim begins to notice that his strength and speed, if not his physique, are starting to erode. When he returns to his lab after a several week absence to ingest more berries, he finds that all of the berry plants have died, apparently from inattention. Efforts to start new plants in the same soil produce no results, and a return to place where he had found the special soil several weeks earlier revealed that the glowing dirt had been washed away by subsequent rains.

Hoping to conserve his strength and energy so that it would last for the remainder of the season, Jim switches from halfback to quarterback because he finds passing less exhausting than running the football. Although the spectacular quality of his performance drops a bit, he proves to be an able quarterback, and the team reaches the season ending game against State University with an unbeaten record. Jim believes that he has just enough strength and energy left for one more game, if he paces himself.

However, on his way to the stadium on the day of the big game, Jim notices a young boy inattentively playing in the road in the path of a speeding automobile. Jim dives for the young boy and knocks him out of harm’s way, but in the process, he breaks his own ankle. Undeterred, instead of going to the hospital, he hobbles to the game.

The ankle clearly slows him down, and by the time that he arrives at the game, time has expired with Hartnell trailing State by a score of 7-6. However, his teammates have just scored a touchdown, and Coach Spencer has courageously ordered the team to attempt a game-ending two point conversion. Depending of the result of this one last play, Hartnell will or won’t end the season as undefeated champions.

Jim convinces his father to insert him into the game, and even though he has to limp to the line of scrimmage, the State eleven are certain that the football is going to be given to the famous “Goliath of the Gridiron.” Jim fakes an end run, but as the defenders converge on him, his teammate who actually has the ball runs into the end zone with the winning score.

In the final scene of the story, Jim has reverted back to his original nerd, agricultural scientist condition, but his girlfriend Betty, awed that Jim would risk his own life and football career to save a young boy, decides to stay with him even though his days as a football star are over.

Here again, the reader applauds the protagonist for his courage (and for getting the girl) and envies him for his season of football glory. No one points out that Jim’s consumption of fruit irradiated with unknown substances from outer space was incredibly risky to his health. Even worse, the giant berries transformed him from a 150-pound weakling into the equivalent of a comic book superhero, but Jim has failed to live up to the obligations of that newly acquired status.

Ordinarily, part of the deal that came with being a comic book superhero in the 1960’s was that principles of fairness prevented the uncommonly powerful figure from participating in ordinary athletic events. Clark Kent never went out for the Smallville High School football team, and the original Flash gave up his athletic career after his first game with super speed when he realized that it would be unfair for him to compete against ordinary slow-footed mortals. Jim, however, denied this implication of his new powers and went out for the team where he seemed to have no objection to running up the score against his outmatched opponents.

So, why do we root for the Vernon Simpsons, Joe Boyds, and Jim Spencers of fiction, cheaters all, when at the same time we hurl brickbats at steroid users like Barry Bonds, Alex Rodriquez, Sammy Sosa, and, perhaps, Ryan Braun?

The answer lies in the fact that our three fictional heroes only turned to the Devil, wood repellent liquid, and radioactive berries after it had become painfully clear that each had been denied by nature that most prized of qualities—athletic ability—and through no fault of their own. Their actions were merely remedial. The three men simply took advantage of the opportunity to use somewhat unconventional means to correct one of Mother Nature’s unfortunate injustices. In doing so, they link themselves to their audience, which is full of people who have dreamed of the same transformative good fortune and who imagine that they would have made exactly the same decision had they been in the shoes of these characters.

But when Bonds, Rodriquez, Sosa, and, perhaps, Ryan Braun—men who are by nature unusually gifted athletes–turn to performance enhancing substances to make themselves even greater performers than they already are, they are engaged in a different kind of cheating. Mother Nature was kind to them, but by trying to go beyond their already good fortune, they seek only to enhance an advantage that they already have over most of their former admirers. By choosing to do this, they further distance themselves from the mass of humanity and from our sympathies.

The fictional Vernon, Joe, and Jim were everymen, and we share their triumphs and failures, because they are like us; Barry, Alex, and Sammy are athletic royalty who should have been content with the God-given natural talent they already had. Instead, they broke rules because they wanted more. Like King Midas, their greed makes them deserving of whatever ill-fate that befalls to them.

On the other hand, if Prince Fielder departs for greener pastures this winter as expected, and if Ryan Braun spends the first 50 games of the season on the suspended list, the Brewers are going to be woefully short of great hitters this spring. I wonder what type of deals Applegate is offering in 2012.

Many baseball fans love baseball statistics and comparing players over the years and even over the decades. Among other problems, the use of PEDs messes up the data. Especially troubling is what Barry Bonds did to the much-venerated career and season home run statistics. It’s simply not as much fun to pour over them as it used to be.

I agree with David Papke. There was something almost theological about the names Ruth, Maris, and Aaron, and the numbers associated with them: Ruth, 60 & 714; Maris 61; and Aaron 755. Each stood for a particular aspect of the human condition that could be admired.

Ruth represented the possibilities of pure enthusiam; Maris, the ability to retain one’s bearing in the face of sudden, unexpected fame and notoriety; and Aaron, perseverance and even-handedness, even in the face of unwarranted prejudice.

Bonds, so far as I can tell, stands only for cheating and having a head like a rock.

People expect an athletic competition to be fair. When players cheat, they and the team owners are perpetrating a fraud on the public. In baseball, the owners knew the players were juiced, but made so many millions off it they didn’t care. Now the baseball record book is worthless. 100 years of baseball history went down the drain. Are the owners offering to give any of that money back? No way. Their greed destroyed the game. How ironic that some people who use illegal drugs go to jail, while others make millions.