Since 1985, Wisconsin’s seven largest cities have followed markedly different paths in their rates of reported violent crime. Two, Waukesha and Appleton, have consistently had lower rates than the state as a whole, while two others, Milwaukee and Racine, have typically had rates that are two to three times higher than the state as a whole. Kenosha and Racine have significantly reduced their rates of violence since the 1980s, while the other five cities have experienced sizable net increases.

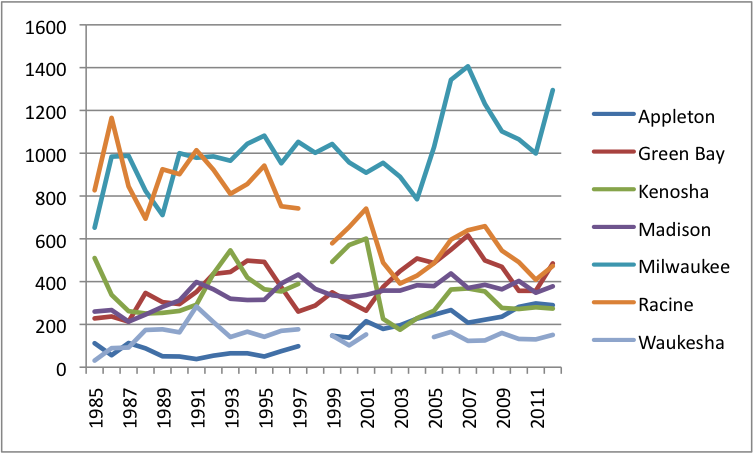

Here are the overall trends, in the form of reported violent crimes per 100,000 city residents:

In recent years, as you can see, Waukesha has easily had the lowest rates and Milwaukee the highest. Earlier, Appleton used to compete with some success for lowest and Racine for highest.

Here are the net changes in the cities’ crime rates from 1985-1987 to 2010-2012:

| Racine | -52% |

| Kenosha | -26% |

| Milwaukee | 28% |

| Madison | 53% |

| Green Bay | 77% |

| Waukesha | 95% |

| Appleton | 210% |

By this measure, Waukesha and Appleton appear to have done the worst in resisting the general state-wide trend to increased violent crime since the mid-1980s, but, of course, their increases were only large relative to very low baseline numbers. Thus, they continue to rank in the top three safest cities on the list. In 2012, Waukesha’s rate of violent crime was about half that of the state as a whole, while Appleton’s was about equal to the state’s.

Kenosha and Racine appear to be the “biggest losers,” although Kenosha’s apparent progress comes with an asterisk. The FBI notes of Kenosha, “Due to changes in reporting practices, annexations, and/or incomplete data, 2002 figures are not comparable to previous years’ data.” In 2001, Kenosha reported 547 violent crimes per 100,000 residents, but only 207 the following year — an extraordinary one-year drop that must, at least in part, reflect the issue flagged by the FBI. Continued low numbers since 2002 may also result in part from that issue.

Breaking down the overall violent crime numbers also reveals notable differences among the cities. Milwaukee has the highest rate of homicide, robbery, and aggravated assault, but Madison leads in rape. Racine leads in burglary (although that crime is not counted in the violent-crime statistics). Interestingly, Waukesha, which has the lowest crime rate in most categories, doesn’t do much better than Milwaukee when it comes to rape.

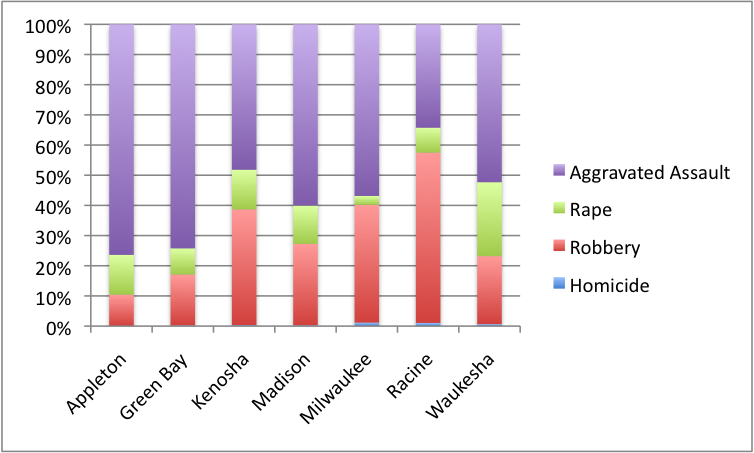

Here was the breakdown of reported violent crimes in each city in 2012:

Note that homicide is such a small part of the violent-crime picture in each of the cities as to be practically invisible on the graph.

The other three types of violent crime play very different roles in each city. For instance, robbery is the major driver of Racine’s violent-crime rate, but is hardly in the picture at all in Appleton. Aggravated assaults dominate in Appleton and Green Bay, but are much less prominent in Racine. It would be interesting to know why Racine has a robbery rate that is triple Green Bay’s and almost nine times that of Appleton, but an aggravated assault rate that is much lower than those of its northern peers.

Rape also varies a lot. For instance, in Milwaukee, rape is hardly in the picture at all, but, in Waukesha, rape is a major driver of the overall rate of reported violence. Waukesha and Appleton are the only two cities in which it seems that your risk of being raped is higher than your risk of being robbed.

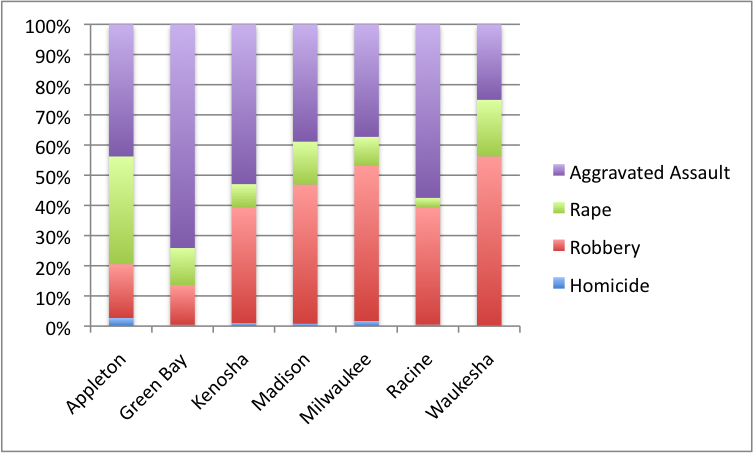

If we look at the breakdowns in 1985, we see a very different picture:

In comparing these numbers with those of 2012, what stands out most is the increased prominence of aggravated assault in the more recent time period. In four of the cities, the aggravated-assault share of violent crime has grown by a large amount. Indeed, in all five cities that have reported net increases in violent crime since 1985, aggravated assault has been the major driver of the overall change. Conversely, the two cities with net decreases in violence, Kenosha and Racine, have benefitted the most from reductions in reported aggravated assaults.

This is a good time to note, as I have earlier in this series, that aggravated-assault numbers do not have a great reputation for reliability. The line is often fuzzy between aggravated assault, which counts as a violent crime in the official FBI numbers, and simple assault, which does not. The uncertainties invite inconsistent or erroneous classifications by police departments, whether inadvertent or intentional. To the extent that aggravated assaults are driving the violent-crime trends depicted in my first graph above, those trends must be interpreted with caution.

When purchasing our home last year, my husband and I debated a move closer to Milwaukee. We researched the crime data and concluded it was best for us to stay far out in the suburbs where the kids can play outside and live a relatively worry free existence concerning crime. The perception alone was enough to endure the long commutes.

The policies at the malls forbidding minors under the age of 18 to shop without a parent in sight makes me question how tourist areas in Chicago, NY City, and Minneapolis do not need such rules. I take my cash and shop elsewhere with my teenage daughter and other children.

The reports that pop up on my smart phone describing attacks on students at two Milwaukee Universities are disheartening. Feeling unsafe is the worst thing a person can experience. It is difficult to become part of a community if one feels threatened or fears that property can be taken at anytime.

The need to educate citizens about crime and how to prevent it is very important. The image of Milwaukee and Wisconsin is at stake. It is even more relevant to empower local communities to have mechanisms to intervene early, to prevent crime, to reduce the factors that cause crime, and to reduce recidivism. Every child in Wisconsin deserves a safe place to play, to live and to learn.