Next week, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, the first non-software fair use case the court has heard since 1994. This has copyright lawyers aflutter, as fair use law has been in increasing disarray for the last 20 years or so, and there is hope that finally the Supreme Court will give lower courts much-needed guidance. Unfortunately, I think the probability is higher of a mush-filled disaster of an opinion, like the one in Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands (2017), that not only gives no guidance, but eliminates the few stable boundaries we have.

Next week, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, the first non-software fair use case the court has heard since 1994. This has copyright lawyers aflutter, as fair use law has been in increasing disarray for the last 20 years or so, and there is hope that finally the Supreme Court will give lower courts much-needed guidance. Unfortunately, I think the probability is higher of a mush-filled disaster of an opinion, like the one in Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands (2017), that not only gives no guidance, but eliminates the few stable boundaries we have.

That’s because fair use doctrine is a poor fit for the way modern courts operate, and there is probably little the Court can do to fix that, but a lot it can do to make the problem worse. But before I get there, I want to lay out in this post what’s at stake in AWF.

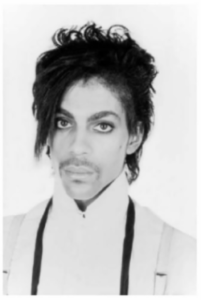

The case involves a licensing deal between celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith and Vanity Fair magazine. Goldsmith, on assignment from Newsweek, had gotten the rock star Prince in her studio just as his career was taking off, and managed to shoot several portraits of him in an abbreviated session.  Prince, according to her testimony, was “really uncomfortable” and soon left. None of the studio photographs ran in Newsweek.

Prince, according to her testimony, was “really uncomfortable” and soon left. None of the studio photographs ran in Newsweek.

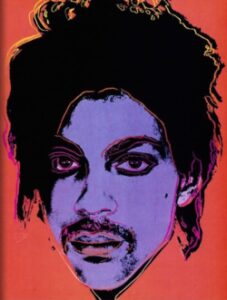

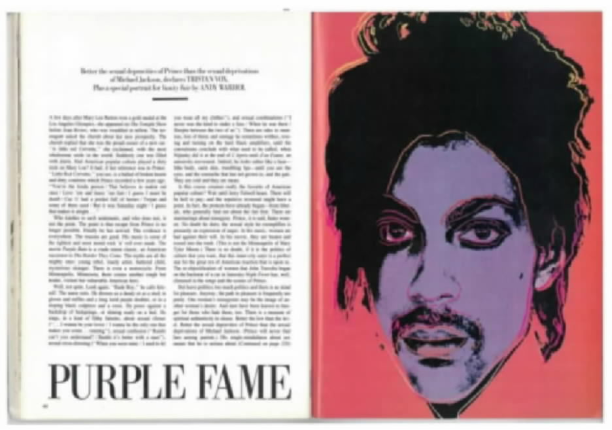

A few years later, Vanity Fair was running an article on Prince and wanted an illustration to accompany it. They licensed the Goldsmith photo from her licensing agency for $400 “for use as an artist’s reference in connection with an article to be published in Vanity Fair Magazine.” Goldsmith wasn’t personally involved in this transaction. Unbeknownst to either Goldsmith or her agency, the artist Vanity Fair hired to do their illustration was Andy Warhol. He produced a derivative work based on the photograph that ran with the 1984 article (below), accompanied by a photo credit to Goldsmith.

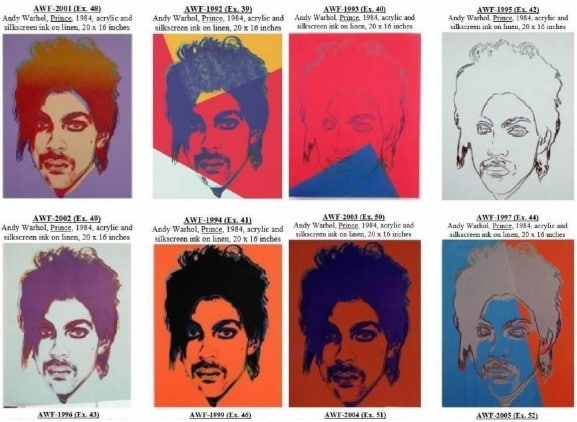

But Warhol didn’t just create the one version. He actually created sixteen different works based on the Goldsmith photograph, which became part of his estate when he died in 1987. Twelve of the physical copies Warhol created are now in the hands of collectors and have been displayed in museums and galleries, and the works themselves have been reproduced in various books, magazines, and promotional materials since 1984.

But Warhol didn’t just create the one version. He actually created sixteen different works based on the Goldsmith photograph, which became part of his estate when he died in 1987. Twelve of the physical copies Warhol created are now in the hands of collectors and have been displayed in museums and galleries, and the works themselves have been reproduced in various books, magazines, and promotional materials since 1984.

Goldsmith was unaware of all of this until 2016, when Condé Nast, Vanity Fair‘s parent company, decided to issue a commemorative magazine in the wake of the artist’s untimely death. They contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation in order to republish the 1984 image.

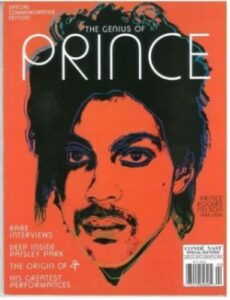

Goldsmith was unaware of all of this until 2016, when Condé Nast, Vanity Fair‘s parent company, decided to issue a commemorative magazine in the wake of the artist’s untimely death. They contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation in order to republish the 1984 image.  At that point, Condé Nast learned of the other 15 works Warhol had created, and they decided to license one of those instead, paying a $10,000 license fee (25% of which went to AWF’s licensor, the Artists Rights Society). Condé Nast ran the “Orange Prince” on the cover of their commemorative issue, with no attribution to Goldsmith.

At that point, Condé Nast learned of the other 15 works Warhol had created, and they decided to license one of those instead, paying a $10,000 license fee (25% of which went to AWF’s licensor, the Artists Rights Society). Condé Nast ran the “Orange Prince” on the cover of their commemorative issue, with no attribution to Goldsmith.

Goldsmith then registered the copyright in the Prince photograph. AWF then preemptively filed suit for a declaratory judgement of noninfringement, and prevailed in the district court, which was then reversed by the Second Circuit. AWF petitioned for cert.

The Stakes for AWF & Goldsmith

What are the stakes in this case? Let’s start with just the remedies if Goldsmith ultimately prevails in the Supreme Court. First of all, the only counterclaim-defendant is the Andy Warhol Foundation, and AWF no longer controls any of the physical copies that Warhol created. (Fun copyright fact: in copyright law, an original work of art is a “copy” — it’s the physical manifestation of the actual copyrighted work, which comprises only intangible expression.) Those copies are owned either by private collectors or by the Andy Warhol Museum, a separate entity. So the only acts directly at issue in this case are the AWF’s licensing of reproductions of the Prince series, not the public display or sale of the physical objects themselves.

Prevailing claimants in copyright cases can get actual damages, statutory damages, attorneys fees, injunctive relief, and possibly even impoundment and destruction of the infringing articles. Impoundment and destruction are typically reserved for straight-up counterfeits. And because Goldsmith did not register her copyright until November 2016, statutory damages and attorneys fees are off the table for any course of infringement (such as the Condé Nast cover) that began before then. But she can still sue for actual damages for those acts, and she can request an injunction.

Based on the license fee for the original photograph of $400, the actual damages per use are not likely to be huge, but multiplied by 15 additional artworks and numerous additional reproductions per work, and even a modest license fee could add up to real money.

More significantly, Goldsmith could also seek an injunction against any further reproductions of any of the Prince series works by AWF. (The original license just covered the November 1984 issue of Vanity Fair.) Depending on the scope of the injunction–assuming one issued–that could mean that AWF could no longer license copies of the Prince series, either for illustrations, for coffee table books, or for posters in museum gift shops.

Even if no injunction issues, AWF will likely be unable to license any further reproductions of the Prince series if Goldsmith wins. That’s because licensing requires copyright ownership, and under Section 103(a) of the Copyright Act, “protection for a work employing preexisting material in which copyright subsists” — such as the Prince series, which employs Goldsmith’s photo — “does not extend to any part of the work in which such material has been used unlawfully.” No fair use defense, no copyright. No copyright, no ability to compel others to pay money to reproduce the images.

Furthermore, although they aren’t counterclaim defendants, anyone holding one of the Prince series works would have to feel nervous about publicly displaying it, or selling it, if Goldsmith wins. If the Prince Series are all infringing derivative works not protected by fair use, then putting them on display in a museum is an infringing public display, and selling them at auction is an infringing public distribution. (There’s no “first sale” exception if the copies in question are infringing.)

Judge Dennis Jacobs offered an intriguing suggestion to get around this consequence in the Second Circuit decision. Fair use is about uses, not works. Perhaps, he offered, some uses of the Prince Series may be within the scope of fair use, even if others are not. Specifically, while licensing the Prince Series as images of Prince competes directly with Goldsmith’s exploitation of her photograph, the creation of the original artworks did not, nor do other sorts of licenses (such as museum posters). Judge Jacobs argued that the Second Circuit’s decision left these other questions open because “Goldsmith does not claim that the original works infringe and expresses no intention to encumber them; the opinion of the Court necessarily does not decide that issue.”

This is a fascinating proposal that I hope to delve into more deeply at some point, but for now I’ll just note two problems. One is that, as far as I know, no previous court has sliced up something like the creation of a related work into infringing uses and noninfringing uses. So it would be novel, which is a strike against it in a common law system.

But second, I can’t find any record of any limitation by Goldsmith of the scope of her counterclaim to only AWF’s licensing, and not the original creation of the Prince Series by Warhol. Goldsmith’s complaint requested an injunction against any use by AWF of “any other Warhol-created works that are substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photo,” which suggests that Goldsmith views the original artworks as infringing, as does the request for a declaration that “any … Warhol-created works that are substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photo … are unauthorized derivative works” and therefore not copyrightable under Section 103(a). Goldsmith’s cross-motion for summary judgement simply requested judgement “in favor of Goldsmith on her counterclaim against AWF for copyright infringement,” and I can’t find anything in the briefing in the Second Circuit that disclaimed an argument that the Prince Series is infringing.

Thus, so far as I can tell, Goldsmith has not forsworn any intention to go after museums and collectors next if she prevails against AWF. Whether she can is an interesting issue.

The Stakes More Broadly

How the Supreme Court decision affects the art and photography worlds more broadly depends on exactly what it says, which is impossible to predict.

A starkly pro-AWF decision could make it impossible for photographers to enforce licenses for artistic reproductions of their work, of the sort that Goldsmith originally sold to Vanity Fair. If an artistic rendering, or modification, of a photograph is enough to bring it within fair use, then any moderately creative retouching or alteration of a photograph should qualify. Stick a few blue lozenges on there and you’ve saved yourself a $400 license fee.

A somewhat less extreme opinion could find fair use in the fact that this was not just any artist’s modification of a photograph, but Andy Warhol’s — in the words of the district court, “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince.” But that risks furthering an already troubling trend in fair use cases — extending greater fair use solicitude to the “rich and fabulous” (in the words of Andrew Gilden and Timothy Greene), and less to the poor and obscure. Andy Warhol is better known than Lynn Goldsmith, so he wins, but woe unto the starving artist from Peoria who tries the same trick with less art-world swooning.

A starkly pro-Goldsmith decision risks, as the many pro-AWF amicus briefs have observed, “a whole generation of artists working today who will be chilled were this ruling to stand.” (Source) The ease of manipulating sounds and images using digital technologies has led to a flourishing of creative re-use of samples and images of famous moments and individuals, much of it in a de minimis or highly transformed way. The rich and fabulous will in many cases still be able to get licenses when they need them, but the poor and obscure won’t, and won’t be able to publish their works on social media or elsewhere without one.

What are the risks of the “mush-filled disaster” I prophesied at the beginning? That no one will know the extent of fair use, just like it’s impossible to say what’s uncopyrightable about a useful article now, and that both photographers and other visual artists will suffer for it. Call that the “Mutual Assured Destruction” result.

Up Next (time permitting): The Road to Transformativeness

Isn’t the Warhol Foundation shooting themselves in the foot? If they win anyone can use Warhol’s works as long as what they create is transformative. It also opens the AI can of worms and destroys the careers for many illustrators and artists as there are already AI art generators being written to copy living artists just to spite them. The same has, can, and will be done for famous dead artists. (Research Kim Jung Gi and the AI created to honor his art after his death).