How likely am I to be called for jury duty? If called, how likely am I to actually be seated for a trial? Do jurors represent a true cross-section of the population? I have wondered about all these questions, and, recently, I came across a report from Milwaukee County Circuit Court making it possible to answer them.

I’ll cut to the chase. If you live in Milwaukee County, your annual odds of receiving a summons for jury duty are either 0 or 1-in-4, depending on your situation. But, assuming you are eligible to be a juror, your odds of actually becoming one are roughly 1-in-100. And while the pool from which jurors are summoned closely matches the demographics of Milwaukee County as a whole, the people who actually show up for jury duty are not so representative.

Odds of Jury Service, from Initial Summons to Sworn Juror

To calculate the odds of receiving a juror summons, we must first subtract the number of people who completed jury duty in the past four years because, in Milwaukee, those people are exempt from service. Last year, the court issued 127,057 summonses, but only 46,199 (36%) of them resulted in someone completing jury duty. Assuming these numbers remain constant, in any given year, about 127,000 summonses will be issued to a pool of about 500,000 people. In other words, if you’re eligible for jury duty, you have a 25% chance of receiving a summons each year. Once you’ve served, you won’t get another summons for at least 4 years.

Receiving a summons is no strong indication that you’ll wind up serving. Of the 127,000 summons issued in 2024, only about 18,000 resulted in somebody actually having to appear for jury duty. In 28,000 cases, the juror was available but their service was cancelled. In the remaining cases, the juror was ineligible or unavailable to serve, the most common reasons being postponement of service (29,300) or non-response (26,200).

If you’re part of the 14% of people receiving a jury summons who actually find themselves sitting in the waiting room at the Courthouse, the odds are good you’ll be sent to a courtroom for voir dire (the legal term for actual jury selection). In 2024, 16,927 people were sent to one of 524 voir dires (it’s possible some people participated in more than one voir dire proceeding). Of those, 72% were questioned and 36% were chosen to be a sworn juror.

To sum it all up, if you haven’t had jury duty for four years, there is about a 25% chance you’ll get a summons next year. If you do get a summons, there is a roughly 36% chance you’ll become eligible and available to serve, a 14% chance you’ll actually have to visit the courthouse, and a 5% chance you’ll be placed on a jury.

Jury Pool Demographics

Of course, those probabilities assume each person has an equal likelihood of selection at each stage of the process. This assumption is basically true in the initial draw of people receiving a jury summons, but it is distinctly not true in the second stage, self-response.

Following state law, the Milwaukee Circuit Court draws its jury pool from a list of state ID card holders provided by WisDOT. This is a good system. As I’ve written, nearly all Wisconsin adults have one of these cards.[i] Indeed, Milwaukee County’s master jury list included about 682,000 names in 2024, which was equal to 97% of the county’s estimated adult population of 701,000.

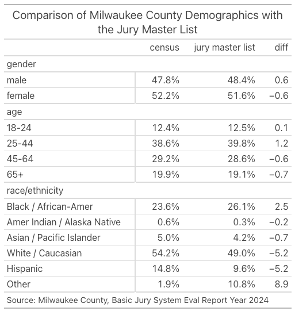

The demographics of the jury master list are about the same as the county’s, as shown in the table below. There are some differences by race, but, as I understand it, these are mostly the consequence of differences between how the Census Bureau and WisDOT measure race and ethnicity.

The big discrepancies occur among the 21% of people who receive a jury summons but don’t respond. In 2024, the rate of non-response was 12% for white, 19% for Asian, 30% for Hispanic, 39% for other, and 44% for Black summons recipients. A much smaller number, about 6% of those receiving a summons, were disqualified from service. Asians and Hispanics were the most likely to be disqualified at 32% and 19%, respectively. This likely reflects language barriers. Wisconsin law requires jurors to be fluent English speakers. Prospective white and Black jurors were disqualified at rates of 6% and 3%, respectively.

Given these statistics, efforts to improve the demographic representativeness of Milwaukee’s juries should focus on the reasons why some people don’t respond to their jury summons in the first place. The summons process itself is demonstrably fair.

[i] My analysis compared DOA records with census estimates derived from vital statistics. I estimated that the share of the adult population with a state-issued ID card lies somewhere between 94% and 100%. Those less likely to have an ID include college students, recent movers from out-of-state, 18 and 19 year olds, and poor people. All else being equal, Black and Asian Wisconsinites are more likely to have an ID than white ones.