[This piece is cross-posted and was originally published in the Yale J. on Reg.: Notice & Comment blog.] On December 8, 2026, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in the landmark case of Trump v. Slaughter. A fundamental issue in the case is whether the statutorily created office of Commissioner for the FTC can include partial restrictions on the President’s ability to remove a Commissioner. The government contends that the statutory removal restrictions impinge on an indefeasible Presidential removal power under Article II.

While the Supreme Court’s recent decisions in Seila Law and Collins have recognized an indefeasible Presidential removal power for some officers, a flood of recent research has undermined historical arguments for a categorical rule that would extend removal at pleasure to all officers or all principal officers. For summaries of this historical literature see Chabot, Katz, Rosenblum & Manners, Nelson, Katz & Gienapp. (My latest paper, The Interstitial Executive: A View from the Founding, adds more fuel to the fire: it introduces a critical body of previously overlooked archival evidence to show that the Washington, Adams, and Jefferson administrations routinely complied with statutory removal restrictions in their officer commissions.)

The government’s reply brief banked on recent precedent from the Roberts Court. It leaned into Seila Law and the unitary understanding of the Decision of 1789 that the Court adopted in that case. At the same time, the government offered an extension of Seila Law that would create further conflicts with the historical record.

Both Seila Law and the officers created pursuant to the Decision of 1789 involved departments led by single officers. Neither Seila Law nor the Decision of 1789 involved statutory tenure protections for officers serving on multimember commissions such as the Federal Reserve or the FTC. As a result, Seila Law is not necessarily at odds with historical evidence supporting these independent multimember commissions. Some of the strongest Founding era examples of tenure-protected officers were those serving on multimember commissions such as the Sinking Fund Commission (described in my work here and here) and the Revolutionary War Debt Commission (described in recent work by Victoria Nourse as well as my new paper).

Early statutes creating both the Sinking Fund and Revolutionary War Debt Commissions assigned executive power to officers whom the President could not remove at pleasure. These formal limitations on the President’s removal power applied to all members of the War Debt Commission and two members of the Sinking Fund Commission. This independent aspect of the Sinking Fund Commission’s structure cannot be explained away by the functional observation that the President could remove other officers on the Sinking Fund Commission at pleasure. See Collins v. Yellen, 141 S. Ct. 1761, 1785 n.19 (2021) (Alito, J.) (raising this functional argument).

The government also claimed (reply br. at 8-9) that early Presidents could nevertheless have removed tenure-protected Chief Justices and Debt Commissioners from their executive posts on the Sinking Fund and Revolutionary War Debt Commissions. This argument flies in the face of the historical record.

As I have explained in earlier work (pp. 1019-20), allowing the President to remove the Chief Justice from the Sinking Fund Commission makes no sense in terms of the Commission’s overall structure or Hamilton’s initial design. Nor is the government’s understanding of the Sinking Fund borne out by the commissions that Presidents issued to Justices who also served in executive roles. President Washington’s diplomatic commission to Chief Justice John Jay indicated Jay would serve in his additional executive role “during the pleasure” of the President. In contrast, Presidents Washington and Adams added no such language to the commissions issued to Chief Justices after they were charged with executive duties on the Sinking Fund Commission. See The Interstitial Executive: A View from the Founding at pp. 23-26.

It was also clear that fixed statutory terms for Revolutionary War Debt Commissioners foreclosed the President from removing them at pleasure. This historical understanding of fixed term tenures has been well-established in scholarship by Jane Manners and Lev Menand as well as Manners’ amicus brief in Slaughter. President Washington also recognized these fixed terms in the commissions he issued to Revolutionary War Debt Commissioners. See The Interstitial Executive: A View from the Founding at pp. 19-20.

President Washington’s omission of a reference to service “during the pleasure” of the President in Revolutionary War Debt commissions is significant. The language in these commissions differs from other fixed term commissions such as those President Washington issued to marshals. Statutes creating marshals provided for both a term of four years and earlier removal at pleasure. Judiciary Act of 1789, ch. 20, § 27, 1 Stat. 73, 87. President Washington mirrored both of these statutory terms in commissions he issued to marshals. Appendices to The Interstitial Executive at pp. 52-53. The statute creating Revolutionary War Debt Commissioners included only a fixed term without allowing earlier removal at pleasure. Act of Aug. 5, 1790, ch. 38, § 9, 1 Stat. 178, 179. President Washington’s commissions to these officers followed the law and referenced a fixed term, without noting removal at pleasure. Appendices to The Interstitial Executive at pp. 55-58.

The government also objected to the possible consequences of historical support for independent multimember commissions. It claimed that Respondent’s argument would prove too much: it might allow Congress to convert the Department of Labor into an independent Commission (reply br. at 2) or, as other unitary scholars have suggested (see Bamzai & Prakash at p. 1844), create a sprawling independent structure that would effectively insulate wide swaths of the executive branch from Presidential control.

These consequentialist concerns do not appear to be grounded in history. They did not manifest themselves in the Founding era or even in the contested transition from the Adams administration to the Jefferson administration. As noted in a recent paper by Jed Shugerman and Gary Lawson, the relatively modest and partial removal restrictions adopted in the Founding era may have instead reflected inherent limits that the Necessary and Proper Clause placed on Congress. The independent multimember structures before the Court fit comfortably within this historical tradition.

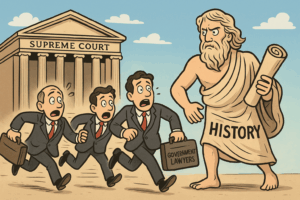

In sum, history has a great deal to say about the structural constitutional questions at issue in Trump v. Slaughter. This history poses a serious obstacle to a categorical rule that Article II empowers the President to remove all officers at pleasure. It seems that the government has asked the Justices to forget some of history’s most important lessons on this topic.