Moral Lessons from the Boomer

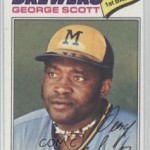

One of the many disappointments of growing older is the awareness that the Big League baseball players you idolized in your youth are dying off. Word came yesterday (July 30) from the pages of the Journal Sentinel that George “Boomer” Scott, former first baseman for the Brewers and Red Sox, has passed away at age 69 in his home state of Mississippi.

One of the many disappointments of growing older is the awareness that the Big League baseball players you idolized in your youth are dying off. Word came yesterday (July 30) from the pages of the Journal Sentinel that George “Boomer” Scott, former first baseman for the Brewers and Red Sox, has passed away at age 69 in his home state of Mississippi.

While he never ranked as one of my all-time favorite players, what I read about Scott in the papers and the sporting press made me like him a lot, and I followed his major league career from its beginning in 1966, when I was in the 8th grade, until his retirement at the end of the 1979 season when I was in graduate school. The lesson that I learned from Scott’s experiences as a baseball player was that life can be a series of very high highs and very low lows and that you just have to ride out the low parts as best you can, although at some point you do have to realize that it is time to call it quits and do something else.

Scott broke into the majors with a very bad Boston Red Sox team in 1966. He won the team’s starting first baseman’s job in spring training and ended up playing in all 162 of the team’s games that season. Scott was a gifted fielder and a perennial gold glove winner during his career, but first basemen are in the line-up to hit. And hit he did in 1966.

Although Scott struck out what was then considered a prodigious 152 times during his rookie year, he also clubbed 27 home runs and drove in 90 runs for a team that was usually short of base runners and which finished in 9th place. Batting around .270 for most of the season, before a late season slump dropped his average to .245, Scott was selected for the All-Star Game in July and finished 3rd in the American League Rookie of the Year voting.

The next year (1967) was, of course, the year of the Miracle Boston Red Sox, when the team catapulted from 9th place to 1st and, after a thrilling four-team American League pennant race that went down to the last day of the season, came within one game of defeating Bob Gibson and the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series.

Although Scott’s power numbers declined slightly to 19 HR’s and 82 RBI’s in his sophomore season, Boomer was an integral part of the success of the 1967 Red Sox, as he cut his strikeouts by more than 20% while raising his batting average to .303. He also played splendidly in the field, saving his fellow infielders from numerous throwing errors and filling in at third base when needed. In spite of his large size (6’2, 200+ lbs), he also proved to be threat on the base paths that year,, racking up 7 triples while stealing 10 bases on a team that was legendary for its refusal to steal bases.

However, just when Scott must have felt like he was on top of the world, his career nearly fell apart. In 1968, everything went wrong, as his batting average dropped 132 points to an unthinkably low .171. His batting power also disappeared, as he compiled an anemic record of only 3 HR’s, 25 RBI’s, and a microscopic slugging percentage of .237 in 124 games. Whether the problem was a series of small nagging injuries or simply that the pitchers of the American League figured out the Boomer’s weaknesses, many observers, myself included, assumed that Scott was headed back to the minors, to be remembered as yet another major league flash in the pan.

However, Scott did rebound from his 1968 disaster. He played his way back into the Red Sox lineup the following spring, and for the next three years he remained Boston’s starting first baseman. While he did not match the offensive output of his first two seasons, he put up acceptable numbers in a time in which pitching so dominated hitting that students of the game still refer to the late 1960’s and early 1970’s as the New Deadball Era.

Scott’s fortunes changed again on October 10, 1971–while I was a sophomore in college—when he was traded to the Brewers as part of a 10-player deal in which he and Brewer outfielder Tommy Harper appeared to be the principal components. This meant, of course, that Scott was leaving the by then regularly pennant-contending Red Sox for the woeful Brewers. In 1972, the Brewers were in just the fourth year of their existence and were starting only their third season in Milwaukee. (In 1969, they had played as the Seattle Pilots.)

Scott’s new team had finished in last place in American League’s Western Division in 1971, and in 1972, after switching divisions, they finished last in the American League’s Eastern Division. However, rather than sulk at his misfortune, Scott arrived in Milwaukee with great enthusiasm and quickly became one of the team’s most popular players.

After a solid 20 HR, 88 RBI, .263 BA in his first Brewer season, Scott had perhaps his best season ever in 1973, as he batted a career high .306 with 24 HR’s and 78 RBI’s. Two years later, after a slight fall off in 1974 (as I entered law school), he tied Reggie Jackson for the American League lead in home runs with 36, while leading the league with 109 RBI ‘s and compiling a career high .515 slugging percentage.

In 1974, he became the Brewers’ highest paid player and was the first Brewer to earn $100,000 a year. By 1976, his salary had increased to $150,000.) (These figures alone are a striking commentary on how baseball’s salary structure has changed over the past 40 years.)

After a solid, but less than spectacular 1976 season, Scott was traded back to Boston, essentially for Cecil Cooper (who was destined to supplant Scott as the first baseman on the Brewers all-time team.) Scott celebrated his return to Beantown with another all-star caliber season, as he blasted 33 HR’s and drove in 95 runs. In spite of Scott’s heroics, the Red Sox fell just short of the pace maintained by their division rivals, the New York Yankees, and finished the season in second place.

1978 is a year of infamy for Red Sox fans and a source of pain not completely eradicated by the World Series championships of the early 21st century. In a year in which everything seemed to be going Boston’s way, the Red Sox, with Scott again playing an important role, jumped into an early lead which the team held throughout the season. However, in September, the team began to falter, and the detested Yankees caught fire and began to narrow the gap between the two teams.

(Coincidentally, I arrived in Boston for graduate school in the midst of this Red Sox collapse in late September, just in time to trade my lifelong allegiance to the Yankees for the agonies of being a Red Sox fan.)

By the end of September, the Yankees had passed the Red Sox and only a last ditch Boston rally allowed the Old Town team to catch the New Yorkers on the final day of the season. The 162 game tie between the two teams then necessitated the infamous season-ending, one-game play-off that was won by the Yankees thanks to banjo hitter Bucky Dent’s unlikely three run homer. The Yankees, of course, went on to win the World Series against the Dodgers.

There was plenty of blame to go around for the Red Sox’ infamous collapse, but much of it fell on the shoulders of George Scott, who had mysteriously stopped hitting during the second half of the season. Although Scott missed the month of May with an injury, he was batting .273 at the end of June., but after that his average dropped 40-points to .233, and he managed only 15 hits in 92 at bats in the critical month of September.

When Scott got off to a poor start in 1979, batting only .224 after 45 games, the Red Sox dealt him to the Kansas City Royals on June 13 for chump change (actually, a player named Tom Poquette). Scott’s previous history suggested that the change of scenery would prompt him to bounce back to his usual excellence as it had before when he changed teams. Initially, this appeared to be happening. Inserted into the Royals starting lineup at first base, Scott batted .305 in his first 21 games as a Royal, although with no homeruns and only 10 RBI’s. However, his hitting then fell off dramatically, and it soon became clear that Scott had no future with the Royals. In mid-August, he received his outright release.

A week later he signed with the Yankees who at the time had fallen to fourth place in the American League East, 14 games out of first place. Ironically, Scott played well for the Yankees, albeit in a limited role as the designated hitter against left-handed pitchers, batting .318 with a .500 slugging percentage in 16 games.

Unfortunately for Scott, on November 1, 1979, while I was studying for my PhD general exams, the Yankees declined to exercise the option clause in his contract, making the Boomer a free agent for the second time that calendar year.

When no offers from major league teams were forthcoming, the 35-year-old Boomer signed a contract with the Yucatan Leones of the Mexican League for the 1980 season. He remained in Mexico for the next five years before concluding, at age 40, that it was time to get on with the rest of his life. Just as Scott was retiring from baseball, I was finishing graduate school and embarking on a career as a law professor.

George Scott played baseball with enthusiasm and dedication. He did not allow the many setbacks in his career to discourage him, and as such he should be a role model for us all.

Scott was also the first professional athlete that I can remember who regularly referred to himself in the third person (usually as “Boomer” or “the Boomer”). It was quite charming at first, though the practice, adopted by others, has become tiresome over the years.