The Late Ray Bradbury Was No Fan of Lawyers

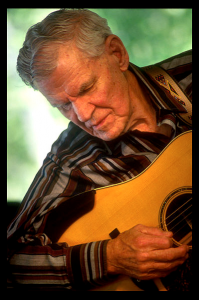

The American writer Ray Bradbury, author of the science-fiction and fantasy classics Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, passed on Wednesday, June 6, at the age of 91.

The American writer Ray Bradbury, author of the science-fiction and fantasy classics Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, passed on Wednesday, June 6, at the age of 91.

Although some members of the American legal profession, like Chinese-immigrant lawyer Michael Yaki, have attributed their decision to become lawyers to reading Bradbury’s anti-thought control novel, Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury himself appeared to have a fairly low regard for lawyers.

There was little in Bradbury’s early life that brought him into contact with the legal profession. Born in Waukegan, Illinois, in 1920, Bradbury was the son of an itinerant telephone lineman. After graduating from high school in Los Angeles in the late 1930’s, he eschewed college (although at least in part for financial reasons). Instead, he proudly continued his own education in the public libraries of Southern California, while embarking on a career as a writer.

Bradbury later admitted that when he first entered into negotiations in the early 1940’s with a filmmaker over the rights to one of his short stories, he had never met a lawyer in his life.

Although he would use lawyers on a number of occasions to enforce his intellectual property rights, Bradbury never seemed to warm up to the legal profession. Lawyer characters appear in his stories only infrequently, and often in unflattering roles.

In his “unfinished” novel, Masks, the protagonist is placed on trial, and his court appointed lawyer enters a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity over the protests and objections of his client.

In his short story, “One for His Lordship, One for the Road,” the arrival of a lawyer is described derisively: “The lawyer, for that is what it was, strode past like Moses as the Red Sea obeyed, or King Louis on a stroll, or the haughtiest tart on Piccadilly: choose one.” Later in the story the lawyer is described as possessing a “great smarmy smirk of satisfaction.” In the story, “Punishment without Crime,” the first words that we read from the mouth of the protagonist’s lawyer are: “It’s all over. You will be executed tonight.”

However, Bradbury’s work suggests not so much a dislike of lawyers as an indifference to them. Usually they appear as the secondary agents of an unwarranted fate. The role of lawyer as lawyer seemed to hold no fascination for him. As he wrote in the foreword to his Mars and the Mind of Man, “Facts quite often, I fear to confess, like lawyers, put me to sleep at noon.” Theories and writers and iconoclastic rebels clearly kept him awake much longer.

I discovered Bradbury’s work when I was in elementary school in the early 1960’s. He was already a legendary figure by that time, and when I saw the notice of his death, I initially had trouble believing that he was just 91. I associated him as much with the years before my birth as I did Hemingway and Fitzgerald. Fame came quite early, and he lived the last two thirds of his life as a literary icon.

After all, who hasn’t heard of Ray Bradbury?