Most people remember Paul Robeson as a star of stage and screen and as a controversial African-American civil rights leader of the early and mid-twentieth century. His performances in “Othello,” “The Emperor Jones,” and “Show Boat” are legendary, as are his renditions of “Old Man River” and the classic Negro spirituals. His support of radical politics and his enthusiasm for the Soviet Union made him a highly controversial figure during the Cold War.

Most people remember Paul Robeson as a star of stage and screen and as a controversial African-American civil rights leader of the early and mid-twentieth century. His performances in “Othello,” “The Emperor Jones,” and “Show Boat” are legendary, as are his renditions of “Old Man River” and the classic Negro spirituals. His support of radical politics and his enthusiasm for the Soviet Union made him a highly controversial figure during the Cold War.

However, before he became famous as an actor and an activist, Robeson was a law student and a professional football player, a combination that brought him to the Marquette College of Law in the fall of 1922.

Here is the story.

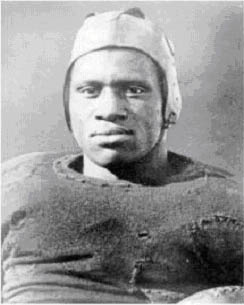

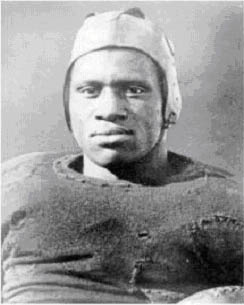

Robeson was born in 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey, and came of age at the height of the Jim Crow era in the United States. He was a superb student in the public schools of Somerville, New Jersey, and he was offered a full academic scholarship by Rutgers University at which he enrolled in 1915. At the time of his enrollment he was only the third African-American to have attended Rutgers, and he was the only black student at the school during the four years in which he was enrolled.

Few college students have ever excelled at the level at which Robeson performed at Rutgers. He graduated first in his class; was elected Phi Beta Kappa as a junior; and won the college’s oratory contest each year that he was enrolled. He also won twelve varsity letters in football, basketball, baseball, and track. His best sport was football, in which he was a first team All-American end in 1917 and 1918.

Few college students have ever excelled at the level at which Robeson performed at Rutgers. He graduated first in his class; was elected Phi Beta Kappa as a junior; and won the college’s oratory contest each year that he was enrolled. He also won twelve varsity letters in football, basketball, baseball, and track. His best sport was football, in which he was a first team All-American end in 1917 and 1918.

After graduating from Rutgers in 1919, he moved to New York where he enrolled at the New York University Law School. After a semester at NYU, he transferred to Columbia, at least in part because of its proximity to Harlem (and the just-underway Harlem Renaissance).

To support himself while in law school, Robeson played for two seasons in the National Football League (or the American Professional Football Association, as it was initially known.) In 1921, he played for the Akron Indians, which were led by player-coach Fritz Pollard, the great running back and the first African-American to coach a predominantly white professional team. Robeson, who played in eight of Akron’s 12 games in 1921, apparently commuted to Akron’s weekend games from New York City.

In 1922, Pollard jumped to the Milwaukee Badgers and apparently convinced Robeson to join him. The Badgers, who joined the NFL that year, played their home games in Borchert Park, the home of the minor league baseball team, the Milwaukee Brewers. Robeson apparently decided that a weekly commute to Milwaukee would be too difficult, so he took a leave of absence from Columbia Law School that fall.

The 1922 Milwaukee Badgers began their season on October 1. On October 17, the Milwaukee Journal ran a story under the heading: “Robeson, Giant Pro End, in M.U. Law Dept.” (Robeson was 6’3” tall and weighed approximately 220 lbs. at that point in his life, which apparently qualified as “giant-size” under the standards of 1922.) The brief story went on to report that Robeson “has taken up a course of review and research work in Marquette university school of law [sic], preparatory to taking the New York state bar examinations late this year.” Counting his semester at New York University, Robeson had already attended law school for three years, so he was already eligible to take the New York bar examination. In 1922, most states required applicants for admission to the bar to have only a specific number of years of legal education rather than a law degree.

While the Journal story seems to suggest that Robeson may have enrolled at the law school, the law school bulletins for 1922 and 1923 do not list Robeson as a student in the fall of 1922, and he is similarly absent from the records of the university registrar.

Robeson’s affiliation with the law school was likely somewhat informal. In the 1920’s, several professors at the Marquette Law School offered “bar prep” courses for students who were preparing to take the Wisconsin bar exam. (The diploma privilege was not extended to Marquette until 1934.) Normally these classes were held after the end of the academic year and just before the summer bar examination. Such classes were technically not offered by the law school, but by individual professors, and thus were open to anyone interested in taking the Wisconsin bar examination. (A decade later, criticism led to the law school requesting its faculty to stop doing this.)

Robeson likely worked out a similar arrangement with one of the Marquette law professors, and this is what the newspaper meant when it referred to a “course of review and research work.” So far as we know, none of the Marquette professors in 1922 were members of the New York bar, but John McDill Fox was a graduate of Harvard Law School who had been successfully passed the Massachusetts bar exam. Given that Fox was one of the professors who regularly offered bar prep courses to supplement his income, he would seem to be the most likely candidate to have directed Robeson’s studies that fall.

(There is an eerie literary parallel here. In Eugene O’Neill’s play, “All God’s Chillun Got Wings,” a black law student named Jim Harris struggles desperately to pass his law school exams and secure admission to the bar. In the play’s first performance in 1924, Robeson was cast in the role of Jim Harris. There is no reason, however, to believe that Robeson knew about the play in the fall of 1922.)

The article also suggests that in the fall of 1922 Robeson was more concerned about the NY bar exam than credits to graduate from Columbia. In any event, the Fall 1922 football season turned out to be a disappointment. Pollard battled injuries throughout the season, and while the Badgers held their opponents to 31 points in their first eight games, they had great difficulty scoring. For the season the team managed only seven touchdowns, one of which was scored by Robeson on a fumble recovery. Robeson missed the season opener, then played in seven games before skipping the season finale, a 40-6 trouncing by the Canton Bulldogs. For the year, the Badgers won two, lost four, and tied three games, with a 10th game rained out but not rescheduled.

After the season, Robeson returned to New York and re-enrolled at Columbia. He graduated from the law school in the spring of 1923 as a member of a class that also included future U.S. Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas. Already immersed in his theatrical career, he apparently never got around to taking the New York bar examination, and he never again played in the National Football League.

The Milwaukee Badgers lasted until the end of the 1926 NFL season when they folded after a dismal 2-7-0 season. In their final year, their roster included third-year Marquette law student Lavvie Dilweg who went on to a highly successful career with the Green Bay Packers and a seat in the United States Congress.

Can we say that Robeson attended the Marquette Law School? Probably not, but he was one of many fascinating individuals whose lives have intersected with our institution.

Thursday’s announcement that the University of Colorado will move from the Big 12 Conference to the PAC 10, and the rumored move of Nebraska from the same conference to the Big 10, appear to be setting off a tsunami of conference switches that threatens to leave the landscape of college sports dramatically different from what it has been during most of the post-World War II era.

Thursday’s announcement that the University of Colorado will move from the Big 12 Conference to the PAC 10, and the rumored move of Nebraska from the same conference to the Big 10, appear to be setting off a tsunami of conference switches that threatens to leave the landscape of college sports dramatically different from what it has been during most of the post-World War II era.