James G. Jenkins:The First Dean of Marquette Law School

When Marquette University acquired the Milwaukee Law School and the Milwaukee University College of Law in the summer of 1908, one of its first tasks was to find a well-known dean for the institution now to be known as the Marquette University College of Law. Although the new faculty was largely recruited from the ranks of the faculty of the two private law schools that it was to be absorbing, Marquette turned to retired federal judge James Graham Jenkins to be its first dean. Although he was reportedly reluctant at first to take the position because of his age, Jenkins eventually agreed and served in that post for seven years.

When Marquette University acquired the Milwaukee Law School and the Milwaukee University College of Law in the summer of 1908, one of its first tasks was to find a well-known dean for the institution now to be known as the Marquette University College of Law. Although the new faculty was largely recruited from the ranks of the faculty of the two private law schools that it was to be absorbing, Marquette turned to retired federal judge James Graham Jenkins to be its first dean. Although he was reportedly reluctant at first to take the position because of his age, Jenkins eventually agreed and served in that post for seven years.

Like many Wisconsin lawyers of his generation, Jenkins was a native New Yorker who had moved to Milwaukee prior to the Civil War. He was born in Saratoga Springs on July 18, 1834, the son of New York City merchant Edgar Jenkins and Mary Elizabeth (Walworth) Jenkins. His maternal grandfather was Reuben Hyde Walworth, a former United States congressman and New York chancellor who in 1844 was nominated, unsuccessfully as it turned out, to the United States Supreme Court by President John Tyler.

Jenkins did not attend college or law school but instead studied law in the office of the New York City firm of Ellis, Burrill, and Davison for five years. He was admitted to the bar at age 21 and worked as “head clerk” for a New York law office for two years. In 1857, he relocated to Milwaukee.

Over the next 31 years he engaged in the practice of law in Milwaukee. According to Jenkins, his first position in the city was in the law office of Jason Downer who paid him $3 per week. However, within in six months he had become a partner with Downer, who in 1864 became a justice on the state Supreme Court. Jenkins later formed a partnership with Edward Ryan and Matthew Carpenter, both legendary figures in the legal history of Wisconsin, and he was later a partner with the less-well remembered James Hickox.

An active Democrat, Jenkins did not serve in the Civil War. However, he was one of the speakers at a mass rally on behalf of the Union war effort held in Wisconsin on July 31, 1862, and in 1863, he was elected Milwaukee City Attorney, a position that he would hold until 1867. After leaving office, he formed his own law firm which was known at various times as Jenkins & Elliott; Jenkins, Winkler, & Smith; and Jenkins, Winkler, Fish & Smith. In 1877, he chaired the state Democratic convention that nominated James S Mallory of Milwaukee for the state’s highest office.

In 1879, Jenkins himself was the Wisconsin Democratic Party’s nominee for Governor of Wisconsin, but he was beaten fairly soundly by Republican William E. Smith who received over 50% of the votes in a three-man race. (There was also a Greenback Party candidate who received approximately 7% of the vote.) In 1881, he was the Democrat candidate for the United States Senate, but the Republican majority in the Wisconsin legislature not surprisingly chose one of their own.

Jenkins’ services to his party did not go unappreciated. In 1885, newly elected Democratic president Grover Cleveland offered Jenkins a position on the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, but Jenkins declined the appointment. However, on June 18, 1888, he was appointed United States district judge for the eastern district of Wisconsin by President Grover Cleveland and his appointment was confirmed by the Senate on July 2. Although Cleveland was defeated for reelection in 1888, he was again elected president in 1892. For his second term, he selected Judge Walter Q. Gresham, a former Republican turned Democrat, as his Secretary of State, and in 1893, Jenkins was appointed Gresham’s replacement as United States Circuit Judge for the Seventh Judicial Circuit. His nomination was confirmed by the Senate and he sat on the Circuit Court until he retired in 1905 at the age of 71.

Shortly after his appointment to the Seventh Circuit, Jenkins was arrested following an indictment by a Milwaukee grand jury which concluded that he and the other directors of the failed Plankinton Bank had improperly taken money from the bank after it had become insolvent. The story of Jenkins’ arrest was reported on the first page of the July 13, 1893 New York Times, but Jenkins resisted suggestions that he resign from the bench, and in November, the indictments were declared “null and void” by the Milwaukee Circuit Court.

Jenkins most famous (or infamous) judicial decision also came in 1893 in the case of Farmers Loan & Trust Co. v. No. Pacific Ry., 60 Fed. 803, in which he enjoined a strike against a railroad under receivership and in doing so coined the phrase “government by injunction” (which he viewed favorably). Jenkins’ injunction, which was interpreted as barring the workers from quitting their jobs, was highly controversial, and there were efforts in Congress to censure him. Eventually he survived the attacks, although the broader aspects of his ruling were narrowed on appeal.

After retiring from the bench in 1905, Jenkins returned to Milwaukee where he remained at least semi-retired, a status that meant that he was potentially available to fill the newly created position of dean of the Marquette University College of Law. Although he was 74 years old in the fall of 1908, there were a number of reasons why he was an attractive candidate for the position of dean. First of all, Jenkins’ prominence as a jurist brought a degree of luster to the law school. In addition to his status as a federal circuit court judge, he also had been awarded honorary doctor of law degrees from the University of Wisconsin (1893) and Wabash College (1897). He was also a member of the nine-lawyer committee that drafted the original American Bar Association Canon of Ethics which was formally adopted in the summer of 1908.

Furthermore, although Jenkins himself had not attended law school, he had been involved with legal education off and on throughout his career. Early in his law practice, he had trained a number of attorneys in his office, including Milwaukee lawyers Horace Upham and Louis Lecher (once Jenkins’ secretary) both studied law under his direction. While a judge, he had also lectured at law schools in Milwaukee and Chicago.

Although the extent of his involvement is not clear, he reportedly lectured at the Milwaukee Law School during its early years, and he was involved with the establishment of the John Marshall Law School. John Marshall, an evening law school located in the Chicago Loop, had been founded in 1899, while Jenkins was still on the federal bench and based in Chicago. He was one of the school’s original faculty members and was the featured speaker at its first commencement in 1902. Apparently his connection to the law school was one that continued until his retirement from the bench in 1905. In 1906, the Chicago school published several of his lectures delivered at the law school the year before which was his final year in the Windy City.

While his teaching probably involved little more than showing up a couple of nights a week and delivering lectures on federal court procedure, his experiences did provide him with some exposure to contemporary legal education, albeit of the night school variety. The Milwaukee Law School and the Milwaukee University Law Schools had provided instruction at night, but the plan for the new Marquette University Law School was to have both a day and an evening program.

Jenkins was also not a Roman Catholic, but that does not appear to have been a major concern of the priests who ran Marquette University in 1908, as all but one of the original law faculty members were Protestants. (The University took the same ecumenical approach to the recruitment of members for its Board of Regents which was founded in 1909. The original regents included Jenkins and a number of other Protestants, and, shortly thereafter, Jews.) Although Jenkins was an Episcopalian, he did have a connection to Roman Catholicism in that his uncle, Clarence Walworth, was a convert to Catholicism and a founder of the Paulist Fathers.

One of the strategies of the new Marquette Law School was to supplement the instruction of the regular faculty (all of whom also practiced law) with lecturers drawn from the ranks of distinguished lawyers and jurists. Presumably, Jenkins’ personal connections in Wisconsin and Illinois helped facilitate this, and the law schools’ first catalog lists 24 such lecturers, including Chicago federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, later the first commissioner of Organized Baseball. Jenkins himself was listed as a lecturer (and not a professor) with the Law of the Sea and Trade Marks listed as his subject areas.

The law school appeared to flourish under Jenkins direction. The enrollment in the fall of 1908 was 127 students, including 77 freshmen, totals that far exceeded those of its two private law school predecessors. Entry level enrollments leveled off after the first year but overall enrollments remained strong, and the number of students reached 166 in the fall of 1915, Jenkins last semester as dean. Moreover, after initially holding classes in Johnston Hall, the law school obtained its own building in 1910, the Mackie Mansion, located on the current site of Sensenbrenner Hall. In 1912, the law school was admitted into the Association of American Law Schools, an organization of law schools committed to higher admissions standards (at least a high school diploma or its equivalent) and an expanded curriculum (a three year law course).

Although Jenkins was a “full-time” dean and occupied one of the few faculty offices in the law school building (the Mackie Mansion), he taught very little and appears to have been somewhat detached as an administrator. He was originally assisted by an associate dean—first Lynn Pease and then Edward Spencer, both former faculty of the Milwaukee Law School—but it appears that neither Jenkins nor the associate deans kept any records at all. In 1911, Arthur Richter was hired as a full-time faculty member and secretary for the law school, but the situation did not appear to significantly improve.

The final years of Jenkins’ deanship were marked by controversy. In 1914, Richter published an article in the American Law School Review (the leading publication devoted to legal education in the early 20th century) that accused the University of Wisconsin Law Department of unfairly lobbying the legislature to defeat a new bar admissions statute that would have eliminated the diploma privilege. In reply, Professor Howard L. Smith of the University of Wisconsin attacked the character and quality of the Marquette Law School and noted, correctly, that Marquette had supported the diploma privilege until it became clear that the Wisconsin legislature until it became clear that the Wisconsin legislature was not going to extend the privilege to an institution that many Wisconsin lawyers still thought of as a night school. Marquette, presumably with the approval of Jenkins, then threatened to sue the University of Wisconsin for libel. This cross-state verbal warfare did little to help the reputation of Marquette and seems not to have harmed its public school neighbor. It also did not help when it was revealed that during the acrimonious Richter-Smith exchange, Richter was secretly trying to secure an appointment to the Wisconsin faculty.

A more serious problem arose in 1915 when Marquette underwent a surprise inspection by the Association of American Law Schools to determine if it was in fact complying with AALS guidelines. Although the 81-year old Jenkins decided somewhat abruptly to step down in the fall of 1915, there seems little doubt that his lax leadership and record keeping had made the investigation more likely. Marquette was able to survive an effort to expel it from the organization the following year, but its poor record keeping clearly hampered its ability to prove its innocence. Jenkins was replaced as dean by faculty member Max Schoetz, who began as acting dean but was given the permanent position the following year.

After stepping down as dean, Jenkins remained a member of the Marquette Board of Regents until his death in Milwaukee on August 6, 1921. He also continued to be involved in a variety of civic affairs and sat on a number of boards of charitable organizations. On September 30, 1917, the Milwaukee Old Settlers Club honored him for his 60 years of residence in the city. After his retirement, he also published an article on the “Admiralty Jurisdiction of Courts” in Volume 4 of the Marquette Law Review.

Although it was written in 1897 for publication in a highly flattering biographical encyclopedia called Men of Progress: Wisconsin Jenkins would probably have been pleased with the following as his obituary:

He has always been a close student of the law, of general literature and of the arts; and these studies have given him a strength and a grace in all his efforts at the bar which not many of his professional associates have attained. Free from the tricks and cunning which too often disgrace the practice of a noble profession, he came to be recognized as one of the foremost and ablest of the bar of Wisconsin. As a practitioner he had his full share of notable cases in the courts, and conducted as large a percentage of them to successful conclusion as have the most prominent of his contemporaries.

His bust can be found on the first floor of Sensenbrenner Hall, just outside the elevator.

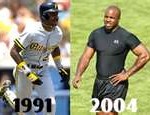

In 1994, after six years of marriage and two children, Bonds petitioned for a legal separation, and his wife subsequently requested a dissolution of the marriage on grounds of physical abuse and infidelity (presumably involving Bonds infamous girlfriend, Kimberly Bell). She also decided to contest the validity of the prenuptial agreement she had signed six years earlier.

In 1994, after six years of marriage and two children, Bonds petitioned for a legal separation, and his wife subsequently requested a dissolution of the marriage on grounds of physical abuse and infidelity (presumably involving Bonds infamous girlfriend, Kimberly Bell). She also decided to contest the validity of the prenuptial agreement she had signed six years earlier. Bonds appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of California, which on July 21, 1999, agreed to hear the case. The following year, in the case styled, In re Marriage of Bonds, 5 P.3d 815 (Cal. 2000), the state’s highest court ruled unanimously that the evidence at trial was sufficient to establish a voluntary waiver on the part of Blanco (or Sun Bonds, as she preferred to be called). Contrary to the holding of the appellate court, the Supreme Court found that the lack of independent counsel was not dispositive, given the lack of evidence of coercion and no real proof of a lack of understanding on the part of the plaintiff. Consequently, it reinstated the judgment of the trial court.

Bonds appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of California, which on July 21, 1999, agreed to hear the case. The following year, in the case styled, In re Marriage of Bonds, 5 P.3d 815 (Cal. 2000), the state’s highest court ruled unanimously that the evidence at trial was sufficient to establish a voluntary waiver on the part of Blanco (or Sun Bonds, as she preferred to be called). Contrary to the holding of the appellate court, the Supreme Court found that the lack of independent counsel was not dispositive, given the lack of evidence of coercion and no real proof of a lack of understanding on the part of the plaintiff. Consequently, it reinstated the judgment of the trial court. Bonds’ “pre-nup” case was followed with great interest in California, and public sentiment was clearly on the side of his ex-wife. (Bonds’ growing reputation for moodiness and surliness in his dealing with the baseball public hardly helped here.) In the next session of the California legislature, State Sen. Sheila Kuehl (D-Santa Monica and in another life, the actress who played the zany Zelda Gilroy on the 1960’s sitcom, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis) introduced a bill that provided that for prenuptial agreements to be valid, both parties to the agreement had to be represented by their own lawyers.

Bonds’ “pre-nup” case was followed with great interest in California, and public sentiment was clearly on the side of his ex-wife. (Bonds’ growing reputation for moodiness and surliness in his dealing with the baseball public hardly helped here.) In the next session of the California legislature, State Sen. Sheila Kuehl (D-Santa Monica and in another life, the actress who played the zany Zelda Gilroy on the 1960’s sitcom, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis) introduced a bill that provided that for prenuptial agreements to be valid, both parties to the agreement had to be represented by their own lawyers. Although the legislative change came too late to help Sun Bonds, the ex-wife did receive some vindication on October 9, 2001, when a California appellate court in San Francisco ruled that the pre-nuptial agreement notwithstanding, Sun was still entitled to half the value of the two homes and an undeveloped lot that Bonds had purchased during their marriage. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, her interest in the three parcels was at least $1.5 million. After this decision, Bonds reportedly settled with his ex-wife for an amount in excess of the Chronicle’s estimate in exchange for her promise to stop suing him.

Although the legislative change came too late to help Sun Bonds, the ex-wife did receive some vindication on October 9, 2001, when a California appellate court in San Francisco ruled that the pre-nuptial agreement notwithstanding, Sun was still entitled to half the value of the two homes and an undeveloped lot that Bonds had purchased during their marriage. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, her interest in the three parcels was at least $1.5 million. After this decision, Bonds reportedly settled with his ex-wife for an amount in excess of the Chronicle’s estimate in exchange for her promise to stop suing him.