Landlords use many different LLCs. A new tool, MKEPropertyOwnership.com, connects them.

Most landlords are small, but the largest 1% of networks own more than 40% of rental units.

By John Johnson and Mitchell Henke.

During the late 2010s, companies owned by a single landlord, Curtis Hoff, generated 5% of all evictions filed in Milwaukee despite owning just 0.5% of the rental stock. His properties racked up code violations at a rate three times that of other large landlord operating in the same parts of the city. The annual number of evictions they filed exceeded 90% of their total housing units.

Despite posting these eye-watering numbers, Hoff’s companies largely flew under the radar until a series of investigative articles in the early 2020s brought them to light, just as he was getting out of the business. That’s because Hoff’s properties were distributed among about 20 different limited liability corporations (LLCs), each of which was the official, legal owner of a different small set of properties.

It’s not that Hoff was trying to hide. Each of these companies began with the letter “A,” a practice dating back to the era when the courts heard each day’s eviction cases in alphabetical order. They all had their taxes mailed to the same address on Good Hope Road—an office building with a large “Anchor Properties” sign.

Still, if you searched the city’s property ownership dataset or the court system’s database, you would have no simple way of telling that all these properties were connected. And so, for years, few people figured it out. As the executive director of the Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee told the Journal Sentinel, “Maybe we’re not connecting the dots like we should be. Nobody’s able to officially track who the problem landlords are.”

To help address this, we’ve built MKEPropertyOwnership.com, a website that lets anyone quickly discover the connections between legal property owners that already exist in publicly available data. A user can simply enter the address of any landlord-owned property in the city, and the website will show that parcel’s official owner, the other owners connected to it, and the total list of properties in the “ownership network.” We also include network-level code violation and eviction annualized rates.

Our process works by standardizing owner names, the addresses at which they receive tax bills, and their corporate registration addresses. We then use network analysis software to identify connected owner names. More methodological details are available on the “About” page. All our data sources are public, and we publish the complete code and source data in this public repository. The data updates each weeknight with the latest version of the city’s property ownership database.

Curtis Hoff no longer owns any properties in Milwaukee, but here is what our website might have shown in 2019, if it had existed. Each green triangle shows a different owner name and each orange circle shows a tax bill address. The lines show the number of times each of the two nodes are connected.

Although Hoff is gone, practically all other large landlords also use multiple companies. For instance, Milwaukee’s largest landlord is Joe Berrada, well-known as the “boulder guy” for his unique style of landscaping. His companies own around 9,000 rental units spread across more than 800 parcels in the City of Milwaukee. Our website identifies over 100 distinct companies associated with Berrada, each of which individually own fewer than 300 units.

Research from many cities shows that landlord size corresponds to different rental practices. Large landlords are much more likely to file evictions. They may also raise rents more aggressively than small landlords. On the other hand, small landlords may employ more discriminatory tenant screening methods than larger, more professional companies. In any case, there is much variation between the behavior of large landlords. As with Curtis Hoff, a handful of companies can account for a greatly disproportionate of eviction cases, for instance. All this means that targeted interventions by housing advocates can be quite successful.

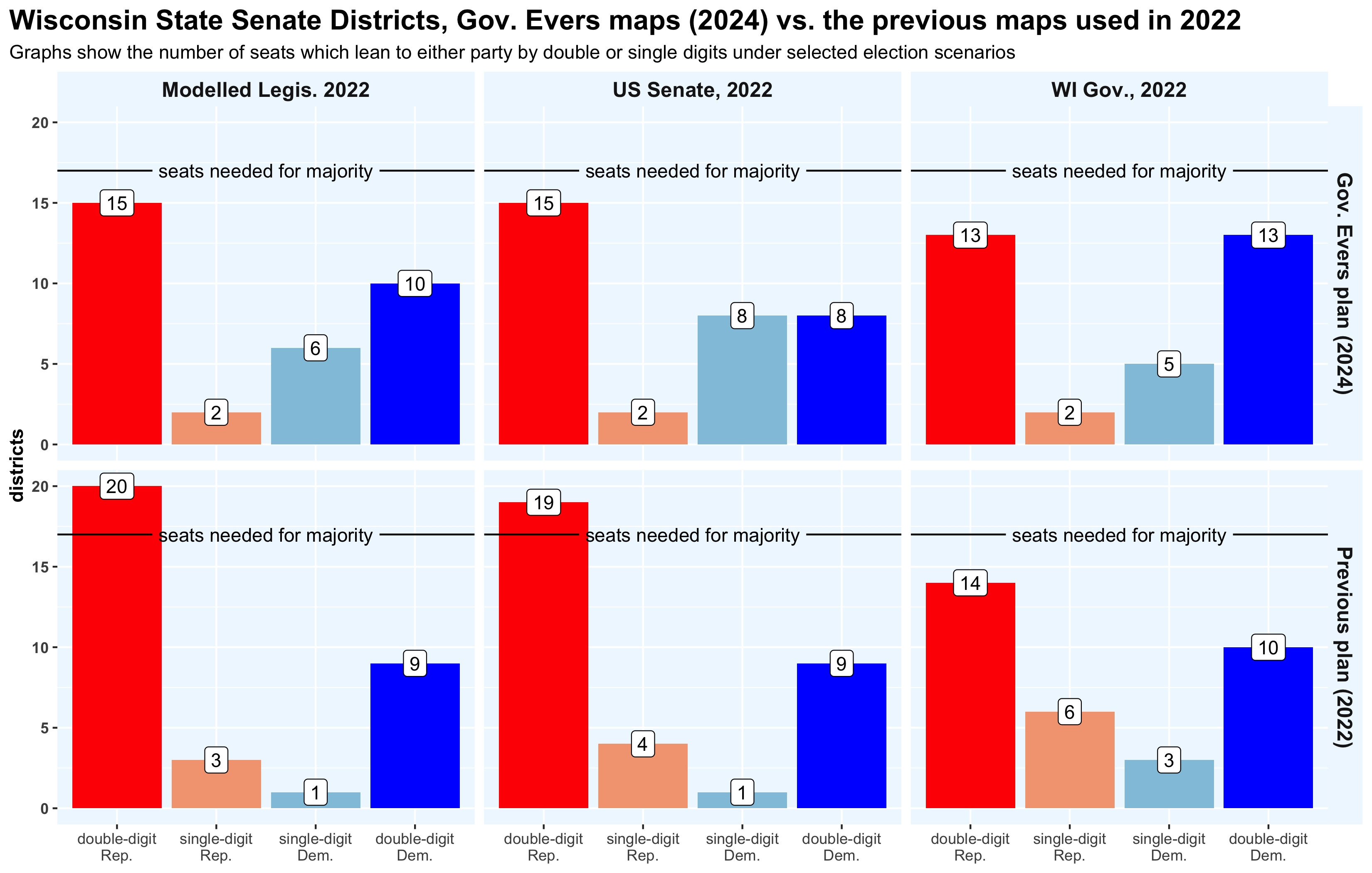

In Milwaukee, we identify about 49,000 landlord-owned parcels in the city containing around 148,000 housing units. This is comparable with the Census Bureau’s estimate of tenant-occupied and vacant housing units. There are about 21,500 distinct owner networks in the data. Of those networks, 15,500 (or 72%) own just a single property. Only about 130 ownership networks own more than 25 rental properties. Nonetheless, those 130-odd networks collectively own more than a fifth of the city’s rental units.

Put another way: the majority of landlords own just 1 or 2 rental units, but the typical tenant rents from a much larger landlord. Our data shows that 44% of rental units are owned by the largest 1% of landlord networks.

We hope this website will be useful to a wide variety of users, including government agencies, community organizations, prospective homebuyers, and tenants; and we are committed to maintaining and improving the project for the foreseeable future.