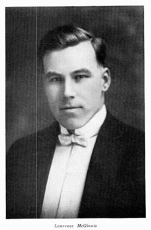

From Marquette Law School to the National Football League, Part II: Larry McGinnis

Laurence J. McGinnis, usually known as “Larry” or “Mac,” was a football teammate and fellow Marquette law student of both Lavvy Dilweg and Biff Taugher. And like both of them, he spent time after law school playing in the National Football League.

Laurence J. McGinnis, usually known as “Larry” or “Mac,” was a football teammate and fellow Marquette law student of both Lavvy Dilweg and Biff Taugher. And like both of them, he spent time after law school playing in the National Football League.

McGinnis was born on July 16, 1899, in Topeka, Kansas. He starred in football at Topeka’s Hayden High, and after a stint in the United States military during World War I, he enrolled at Washburn University in his hometown. He played varsity football at Washburn, but in the fall of 1921, he relocated to Milwaukee where he enrolled in the Marquette Law School. At the time of his arrival in Milwaukee, he was 22 years old.

In 1921, Marquette required law students to have completed one year of college training, but the law school also operated a four-year program that combined law and undergraduate courses for those students who wanted to begin law school without any prior college training. McGinnis enrolled in the four-year program, even though he had apparently attended Washburn for two years.

Like Biff Taugher, McGinnis entered Marquette in an era when it was not unusual for law students to play on university athletic teams, so long as they had not exhausted their eligibility playing elsewhere. In 1921 and 1922, the 6’1″, 210-pound McGinnis starred for Marquette as an offensive and defensive lineman who also handled the kick-off chores.

A broken nose forced McGinnis out of the line-up for several games in 1921, but he returned to anchor the Marquette line in the next to last game of the season, the previously mentioned contest with Notre Dame. Although Notre Dame prevailed, 21-7, McGinnis won praise as he, in the words of the Marquette Hilltop, “repeatedly stopped the onslaught of the great scoring machine which Knute Rockne had developed.” The 1921 team finished the season with a record of 6-2-1, with the only other loss being a 3-0 defeat by Creighton.

In 1922, McGinnis, in his final year of college eligibility, was chosen as the captain of the Marquette team. Under his leadership, the Marquette eleven (which now included Lavvie Dilweg) put together one of the greatest seasons in the school’s history, going 8-0-1, and outscoring its opponents 213-3. (These opponents included Creighton but not Notre Dame.) The only two “blemishes” on its record were a 0-0 tie with Ripon in the second game of the season and a field goal surrendered to the University of Detroit in a hard-fought 6-3 victory for Marquette.

When McGinnis left the field near the end of the final game of the 1922 season, a 38-0 drubbing of South Dakota State, it was reported that “a mighty cheer arose and the students and fans stood.”

Although McGinnis was not eligible to play for Marquette in 1923, he remained enrolled in the law school for two more years. He also shifted his extracurricular activities to college theatrics and the school’s Kansas Club. He joined the theatrical Harlequin Club and during his senior year played one of the lead roles in a student-written production, “Chinese Money,” which was apparently an effort at musical comedy.

The Marquette Kansas Club was a social organization made up of students with ties to the Jayhawk state. The organization’s mission was to “spread the fame of Marquette throughout the South,” and especially in Kansas and Oklahoma. During the 1924-25 academic year McGinnis chaired the Kansas Club, which counted a total of 21 members. McGinnis had also served as chairman of the 1922 Law Dance, the major event of the Law School social season.

Although McGinnis was an outstanding football player, his absence from the gridiron was hardly fatal in 1923, as the renamed Marquette Golden Avalanche was undefeated and untied in eight games, with victories over national powers Boston College and the University of Detroit, as well as over pesky Ripon College. Even without McGinnis, the team contained a substantial law school presence as the roster included at least five law students: Charles Regan (end), Earl Kennedy (center), Joseph Bennett (halfback), Irving Meheigan (guard), and Lavvy Dilweg (end), with Regan, Kennedy, and Dilweg serving as starters, and Kennedy acting as team captain for part of the season.

Moreover, the end of McGinnis’ playing career at Marquette did not spell the end of his football career in Milwaukee. During the 1923 season, he signed with the local professional team, the Milwaukee Badgers who had entered the NFL the previous year. This enabled him to both go to class at the law school and to practice with the team during the week and then travel with the Badgers to their games on the weekend (when they were not in Milwaukee.)

On a team that finished 7-2-3, and tied for third (with the Packers) in a 21-team NFL, McGinnis played an important role as a back-up lineman. Playing center, guard, and end, he appeared in seven of the team’s 12 games. In three of these games he was in the starting line-up when injuries made the regular starter unavailable. He was also the only former Marquette player on the Badgers.

The following year, 1924, he started 12 of the team’s 13 games at either guard or center. Unfortunately, the team’s record declined to a mediocre 5-8-0, as the team fell out of contention for the league championship. On November 9, the team was still 4-3-0 with an outside chance of being again among the league’s leaders, but over the next 21 days, the team dropped five of six games. In 1924, McGinnis was joined on the Badger roster by his former Marquette teammate, quarterback Red Dunn (who attended the college, but not the law school).

The 1924 season proved to be the end point of McGinnis’ football career. McGinnis graduated from the law school in the spring of 1925, and on the following September 27, he married Ruth Zwickey of Iola, Wisconsin. Zwickey and McGinnis had met as fellow students at Marquette where Ruth was a nursing student. The McGinnis-Zwickey wedding occurred exactly one week before the 1925 season opener for the Milwaukee Badgers, but at that point it was clear that McGinnis had decided to abandon football for a career in law.

Instead of donning the pads and moleskin that fall in Milwaukee, he opened his own law office in the town of Amery, which was located in Polk County in northwestern Wisconsin. A year after beginning his practice, McGinnis was appointed to the county bench, and in 1930, he was elected Polk County State’s Attorney, a position that he held for six years. He voluntarily returned to private practice in Amery in 1936, and for the next twelve years he practiced law and served in a variety of roles in community activities. He was president of the Amery Community Club and chairman of the Red Cross fund, and was an active member of the American Legion and the Knights of Columbus.

McGinnis died unexpectedly of a heart attack on March 21, 1948, in Amery, several months shy of his 49th birthday. His wife lived until 1982. The couple had no children.