Before the Sports Broadcasting Act: Professional Football Fifty Years Ago

Warning: This essay contains pure, unadulterated nostalgia for the professional sports regime of the middle third of 20th century America.

Warning: This essay contains pure, unadulterated nostalgia for the professional sports regime of the middle third of 20th century America.

I remember watching the 1960 World Series on television, but the first year that I really followed major league baseball was 1961, the year of Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle’s historic assault on Babe Ruth’s single season home run record. When the baseball season was over, my new-found enthusiasm for sports led me to become a pro football fan as well.

The 1961 season was the second in which the National Football League faced competition from the upstart American Football League. Although everyone I knew and everything I read viewed the NFL as the superior league, no one seemed to deny that the AFL was a major league. As with baseball, my two primary sources of sports information were the sports page of our daily newspaper, the Roanoke Times, and sports cards that came packaged with bubble gum, the purchase of which consumed most of my meager resources.

The local drug store from which I purchased most of my football cards carried the 1961 Fleer Pro Football set, which contained 220 player cards representing all 8 AFL teams and 14 NFL teams, including the expansion Minnesota Vikings. (There were only seven Viking cards, and the player pictured on each was shown in the uniform of his previous NFL team.) Cards came five to a pack with a piece of bubble gum. AFL and NFL cards were never mixed together, so you knew immediately whether you had gotten an AFL or a generally-perceived-to-be-much-more-valuable NFL pack.

For me, picking a favorite football team in 1961 was a real challenge. My home town in southwest Virginia was more than 300 miles from any city with a team; neither of my parents was a professional football fan, and my family, having always lived in rural Virginia and West Virginia, had no connection to any large city. In baseball, I had rooted for the New York Yankees and the Milwaukee Braves (the former because of Maris and Mantle and the latter because my youth league team was called the Braves).

However, these baseball connections did not automatically transfer into my becoming a New York Giants or a Green Bay Packer fan. (I now regret not picking up on the coolness of the Packers until I came to Marquette in 1995. I think the Green and Gold uniforms, which closely resembled those of the Narrows Green Wave, my town’s arch rival, eliminated them as a rooting interest.) I did root for the New York Titans (now Jets) in the AFL, but the AFL counted for very little among my circle—my friend Tommy Powell once offered to trade me his entire collection of AFL cards for my one Johnny Unitas card, but I refused the offer.

The ability to follow an NFL team in Pearisburg, Virginia, in 1961 was restricted in several ways. One was the limited number of television and radio options for following the NFL generally. The one local radio station did not carry any football games at all, and the options available on the one television station that we received were, needless to say, fairly restrictive.

Although the Sports Broadcasting Act was passed in the fall of 1961, the 1961 season was the last in which the previous broadcasting rules applied. Basically, because of judicial interpretations of the Sherman Act’s application to the NFL, the league was prohibited from negotiating a collective broadcasting contract with an individual television network (of which there were then three). As a result, individual teams negotiated with the networks or with independent stations for the rights to their home games. (Allowing the collective sale of broadcast rights was the major change brought about by the Sports Broadcasting Act.)

Throughout the 1950’s, most NFL teams sold their broadcast rights to CBS, but for the 1960 and 1961 seasons, the rights to the home games of the Colts and Steelers were acquired by NBC. In contrast, the AFL games had been sold as a block to ABC shortly after the league’s founding in 1960, apparently on the assumption that the Sherman Act did not apply to the AFL in the same way it applied to the NFL. (Presumably, this was rooted in the notion, given the nature of its founding where teams were started from scratch, that the AFL constituted a single economic entity whereas the NFL was a combination of teams, most of whose economic existence predated their membership in the NFL.

Unfortunately, because of the location of our house (and probably because of the technological limitations of our television antenna which had been purchased in 1955 or 1956), we could only pick up the signal of one television station, WSLS-TV in Roanoke, which was an NBC affiliate. Consequently, the only games I could watch featured either the Colts or the Steelers and whomever they might be playing. (The two teams, which were in different divisions, did not play each other in 1961.) Some people in the town with a better location (or a better antenna) could pick up a CBS station, but no one got ABC.

The other factor affecting the object of my fandom was the enormous popularity of the Baltimore Colts in southwestern Virginia. As far as I could tell, all of the pro football fans in my home town rooted either for the Colts or the Washington Redskins (which was the closest team.) Older adults could probably remember when the Redskins were a top team, but in the recent past they had been dreadful. (Just ask Professor Kossow, who even then was a season ticket holder.) In 1960, the Redskins were 1-9-2, and the year before that, which to me in 1961 seemed like ancient history, they were only 3-9-0. It was also clear to me that most Colts fans were of the view that only life’s losers rooted for the Redskins.

In contrast, the late 1950’s and early 1960’s were the Golden Age of the Baltimore Colts. The Colts had won NFL championships in 1958 and 1959, and the names of their star players—Johnny Unitas, Lenny Moore, Kenosha’s Alan Ameche, Raymond Berry, Gino Marchetti, Eugene “Big Daddy” Lipscomb, L. G. “Long Gone” Dupre, and Art “Fatso” Donovan—were as well known in the Mid-Atlantic region as the Lombardi Packers would be in 1960’s (and later) Wisconsin. The Colts appeared to be on their way to a third straight championship in 1960 until they mysteriously lost their last four games of the season, and were replaced as Western Division champions by Vince Lombardi’s upstart Green Bay Packers, which, before Lombardi’s arrival, had spent most of the 1950’s competing with the Redskins for the title of “sad sack” of the NFL.

So I began the season unsure of which team I liked best. My next door neighbor, Tom Givens, convinced me that I should be rooting for the Redskins, so I started off trying to be a Redskins fan, but after the still all-white team started the season 0-9-0 while being outscored 245-68, I sort of gave up on them. As it turned out, it didn’t get much better for the Skins, who finished the season 1-12-1 with a tie and a final game victory over the Dallas Cowboys, which were in their second year of existence.

Watching the Steelers on television on a regular basis made me sort of a Steelers fan, and they did have some very cool players: halfback Tom “the Bomb” Tracy (who specialized in the halfback option pass, although he only rarely completed his tosses), fullback John Henry Johnson (presumably named after the legendary railroad worker who was a local hero where I grew up), and quarterback Bobby Layne, whom the announcers treated like some revered elderly figure and who kicked extra points, but not field goals.

However, the Steelers didn’t do that well either. They lost their first four games—only one of which was televised–before finally getting their first win of the season, a shutout of the Redskins. (Who else?) Plus, Bobby Layne was injured and missed the middle half of the season, and even though the Steelers won four of their next five games after the 0-4 start, they dropped three of their last five to finish 6-8-0. By mid-season, I was basically a Colts fan.

But the Colts also had problems. The shortcomings that had plagued the team at the end of the 1960 season, which were probably personnel related, continued in the early part of the 1961 season. After opening with a narrow 27-24 victory over the Los Angeles Rams, the Colts lost four of their next six games, including losses to the Packers and Lions, which along with the Colts had been the preseason favorites in the NFL West, and two defeats at the hands of the Chicago Bears in the space of 15 days.

At mid-season, the Packers were in first place in the West with a 6-1-1 record while the Colts were in fifth place, trailing not just the Packers, but also the surprising Bears, the 49ers, and the Lions.

The Colts appeared to be on the verge of rallying in the second half of the season when they pasted the Packers, 45-21, in a November 8 game in Baltimore. Unfortunately, the Colts dropped their next game to expansion Minnesota Vikings, by an embarrassing score of 28-20. This loss left them three games behind the Packers (who that same day bested the Bears 31-28 in Wrigley Field) with only five games to play.

Although the Colts won four of their last five games, the Packers continued to win and actually clinched the West Division championship at the end of Week 12, two weeks before the end of the regular season.

The race in the NFL East Division was much closer, and basically featured a three-way contest among the defending champion Philadelphia Eagles, the New York Giants, and the Cleveland Browns that lasted until the final day of the regular season. The Eagles either held or shared first place for 10 of the first 12 weeks of the season, but at the end of Week 12, the Eagles and Giants were tied for first with records of 9-3-0, with Cleveland a game behind at 8-4-0.

On Sunday, December 10, the Division leaders squared off against each other in Philadelphia. The Eagles led 10-7 after the first quarter, but the Giants then replaced starting quarterback Y.A. Tittle with his aging back-up Charlie Conerly. Conerly rallied his teammates, throwing three touchdown passes and no interceptions as the Giants held off their rivals to the south and came away with a 24-20 victory. This put the Giants one game up on the Eagles with one game to go, assuring them of at least a tie for first place. That same day, the Browns were eliminated by a close 17-14 loss to the Bears in Chicago in a game in which the Browns had led 14-0 in the 4th quarter before faltering.

To retain the East Division title, Philadelphia had to defeat the Lions in Detroit the next weekend and hope that Cleveland could travel to New York and win out over the Giants. In that case, the two teams would play a 15th game to determine the division champion.

The Eagles defeated the Lions, but it was for naught as the Giants and Browns battled to 7-7 in Yankee Stadium. With a record of 10-3-1, the Giants edged the 10-4-0 Eagles by a half game.

Two weeks later, on New Year’s Eve, the Packers and Giants met in Green Bay for the 1961 NFL Championship. Although the Packers had played in the 1960 championship game, their last NFL title had come in 1944, when they bested the Giants 14-7 in New York’s Polo Grounds. The Giants were not strangers to the title game either; in fact, although their last NFL title had come in 1956 when they trounced the Chicago Bears, 47-7, Gotham’s team was playing in the championship tilt for the fourth time in six years.

The 1961 championship was played in 17-degree weather with a 10-mph wind in the Packers still new stadium, which had opened in 1957. Known originally as “City Stadium” or “New City Stadium,” the structure would not be renamed Lambeau Field until 1965. The game was televised on NBC, which held the exclusive rights to broadcast the NFL championship game from 1955 through 1963.

The game itself was a complete anti-climax. After a scoreless 1st quarter, Packer halfback Paul Hornung, the NFL’s leading scorer, ran the ball over the goal line from six yards out. Quarterback Bart Starr then tossed TD passes to wide receiver Boyd Dowler and tight end Ron Kramer. When the next Packer drive stalled at the 10-yard line, Hornung finished off the 24 point quarter with a 17-yard field goal. (In 1961, NFL goal posts were positioned on the goal line, hence the 17 yard field goal.)

In the third quarter it was more of the same, with Horning kicking a 22 yard field goal, and Starr tossing another TD pass to Ron Kramer. The only scoring in the final quarter was a third field goal by Hornung, this one from 19 yards out, giving him a total of 19 points for the game (one touchdown, four extra points, and three field goals)

For the game, the Packers outrushed the Giants 181 yards to 31, with Hornung and Jim Taylor leading the way with 89 and 69 yards, respectively. Starr passed for 164 yards and three touchdowns, compared to a combined 119 yards for Tittle and Conerly. Ron Kramer led the Packers in receptions with four (two for TDs), and both Dowler and Hornung pulled in three catches. Popular wide receiver Max McGee was shut out in the receiving department, but no one really noticed.

The Packer defense was particularly effective that day, as the 37-0 score suggests. In addition to holding the Giant running backs to 31 yards on 14 carries, the defense sacked Tittle twice for losses of 20 yards and intercepted him four times. As in the earlier Giant-Philadelphia game Charlie Conerly was brought in off the bench when Tittle faltered, but in the championship game there would be no magical comeback, as Conerly was able to complete only four of eight passes for a paltry 54 yards.

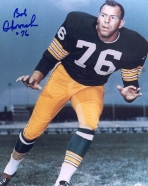

The names of the starters for the Packers in the 1961 NFL championship game still resonate deeply for many Wisconsin sports fans. The offensive backfield that day included Bart Starr (QB), Paul Hornung (HB), Jim Taylor (FB), and Boyd Dowler (FL). The ends were Max McGee and Ron Kramer, and the offensive line included center Jim Ringo, guards Fuzzy Thurston and Forest Gregg, and tackles Norm Masters and Bob Skoronski. (Starting guard Jerry Kramer missed the game with an injury, forcing Forest Gregg to move to guard from his normal starting tackle position.)

The Packer defensive line was made up of defensive ends Willie Davis and Bob Quinlan and defensive tackles Henry Jordan and Dave Hanner. The starting linebackers were Bill Forester, Dan Currie, and middle linebacker Ray Nitschke, while the defensive backfield included cornerbacks Hank Gremminger and Jess Whittenton, strong safety John Symank, and free safety Willie Wood. Wide receiver Boyd Dowler handled the punting, and Hornung did the place-kicking.

The 1961 NFL season did not actually end, however, until January 14, 1962, the date of the post-season all-star game officially known as the East-West Pro Bowl game. It too was televised by NBC.

I can still remember listening to the game sitting on the floor in our den. I say listening because some time after Christmas 1961, a tube blew out in our television set, a fairly common occurrence in the pre-printed circuit era of electronics. Although the sound continued to work, the screen remained completely blank, effectively turning the television into a radio. When this happened, my parents invariably treated it as a kind of divine signal that my brother and I needed to take a break from TV, and they usually waited a few weeks before getting the tube replaced.

Consequently, I was forced to listen to the game and imagine in my mind what turned out to be the most exciting professional football all-star game of all time. The West led for most of the game, jumping out to a 14-3 lead in the first quarter. However, the East regrouped and managed to narrow the gap to 17-10 at the half. At the end of the third quarter, the West still led, 24-16, as both teams scored touchdowns, but the East’s extra point attempt was blocked by Green Bay Packer (and University of Virginia graduate) Henry Jordan.

However, the East offense caught fire in the final quarter, and put a quick 14 points on the scoreboard when Title passed two yards to his team Alex Webster for one touchdown and fullback Jimmy Brown ran 70 yards for another.

With the East now in the lead, 30-24, the West offense continued to sputter, and with less than two minutes to go in the game, the East had the ball with the intention of running out the clock with a series of rushing plays. However, a crushing tackle by Chicago Bear linebacker Bill George caused an uncharacteristic fumble by Jim Brown, which was recovered by George on the East’s 42 yard line, providing the West with one final shot at winning the game.

West quarterback Johnny Unitas quickly completed a pass of 14 yards to tight end Mike Ditka of the Bears, and then on the next play, one of 15 yards to his Baltimore Colt teammate Lenny Moore. However, a second pass to Moore fell incomplete, and with only seconds remaining, the West had the ball on the twelve-yard line. On the game’s final play, Unitas hit Los Angeles Ram halfback Jon Arnett in the back of the end zone for a game tying six points, and with time expired the West converted the extra point for the victory.

In spite of his fumble, Jimmy Brown was named the player of the game while top lineman honors went to Henry Jordan.

It was a great way to end a great season. We talked about it the next day in my Fourth Grade class, and a half century later, I still remember the 1961 season.