How Wisconsin Split Its Ticket Once Again

What Ward Data Shows About Shifting Support by Education, Race, Age, Income, and More

Donald Trump won Wisconsin’s 2024 presidential election by just shy of 30,000 votes, after losing the state by 21,000 in 2000 and winning by 23,000 in 2016. Meanwhile, Tammy Baldwin won reelection by a similarly slim 29,000 votes. This, after Ron Johnson won his 2022 reelection campaign by 27,000 votes.

While other parts of the country (e.g., New York, New Jersey) saw big swings to the right, Wisconsin shifted more modestly. Trump eked out a win, but not by enough to pull Eric Hovde along with him. Republicans won most of the competitive seats in the State Assembly, likely keeping a comfortable 9-seat advantage. But Democrats swept all 4 State Senate targets, making them marginal favorites to win the chamber in 2026.

What the 2024 Republican swing lacked in magnitude it made up in its breadth across Wisconsin. Communities of all kinds moved toward the Republicans. Trump improved over 2020 in all but 4 of the state’s counties.

Trump increased his vote share since 2020 in 70% of the state’s municipalities and 62% of its wards. Here are 5 graphs showing how Wisconsin wards have trended since 2016.

Click here for an interactive map of all Wisconsin wards.

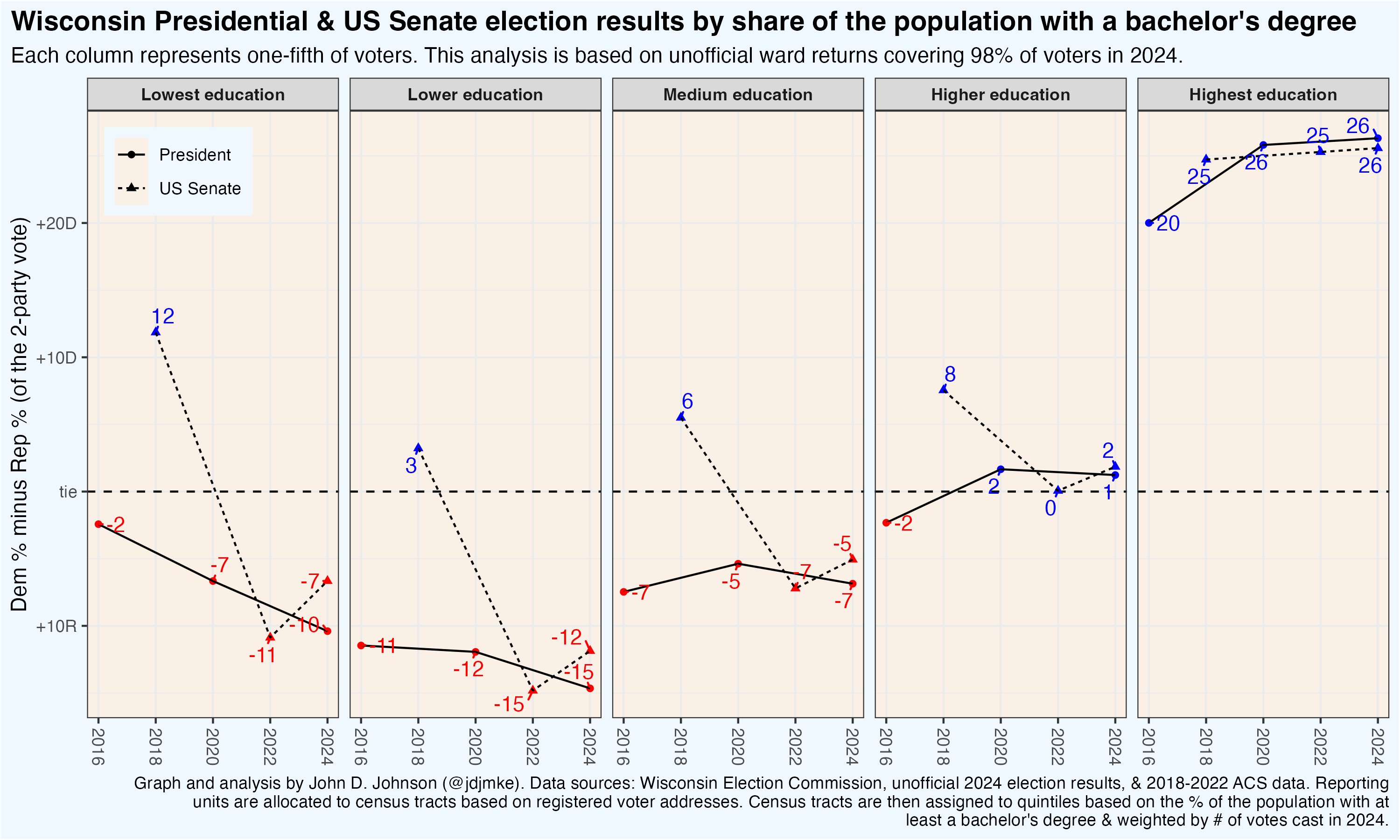

Education

As everyone knows by now, our electorate is increasingly polarized by education. The least college-educated places vote more for Trump and the most educated places have shifted toward the Democrats. That was the trend between 2016 and 2020 anyway.

A big part of why Trump won Wisconsin in 2024 is that he continued to make gains in the wards with the lowest levels of college education, while Harris only matched Biden’s performance in the most educated wards.

Still, the net gap has expanded from 22 points separating how the most and least-educated wards voted in 2016 to 33 points in 2020 and 36 points in 2024.

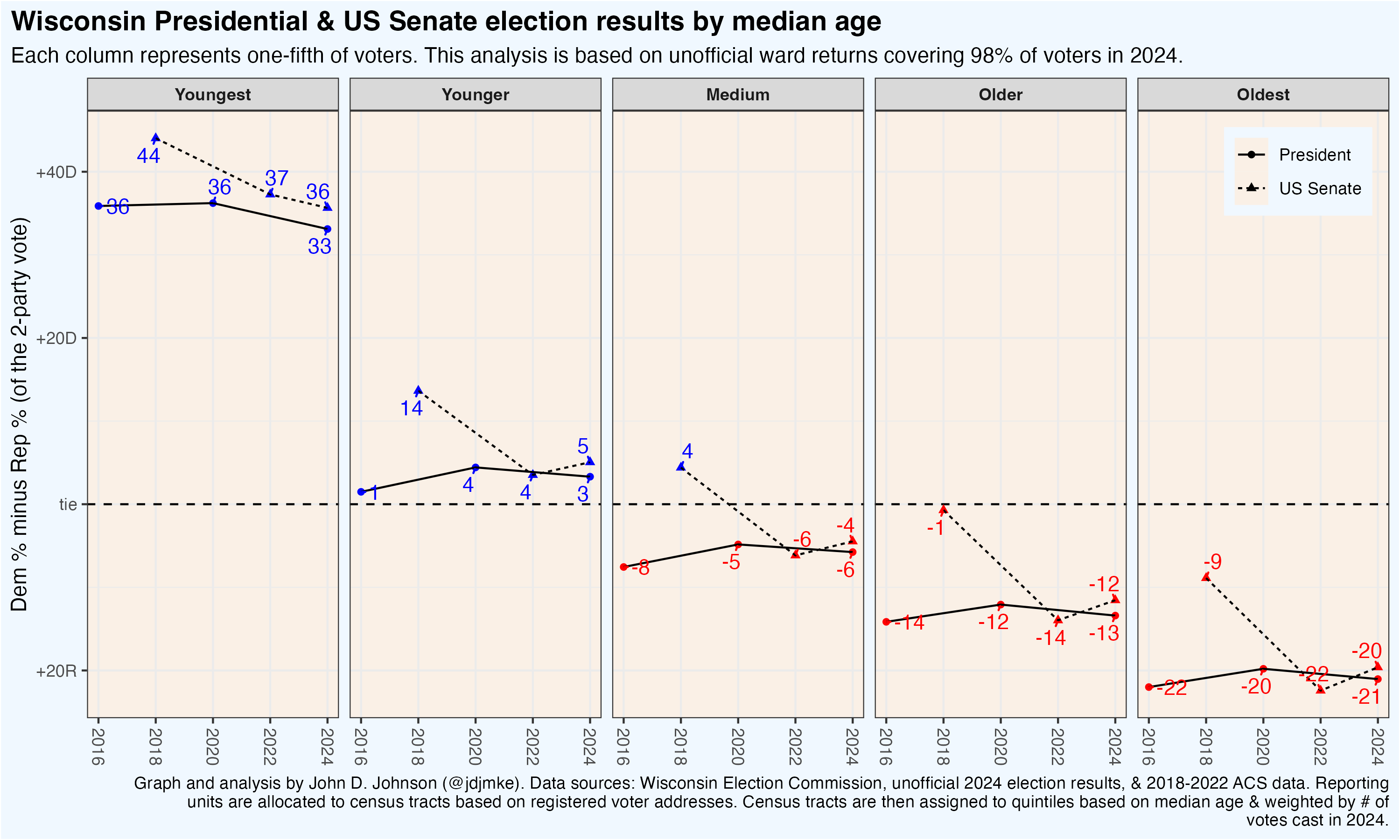

Age

Young people are more liberal and old people more conservative, but in recent years these differences haven’t grown much—at least at the ward level. The oldest wards moved toward Trump by about 1 point in 2024, similar to the state average. Notably, the youngest set of wards, while still very Democratic, shifted 3 points toward Trump.

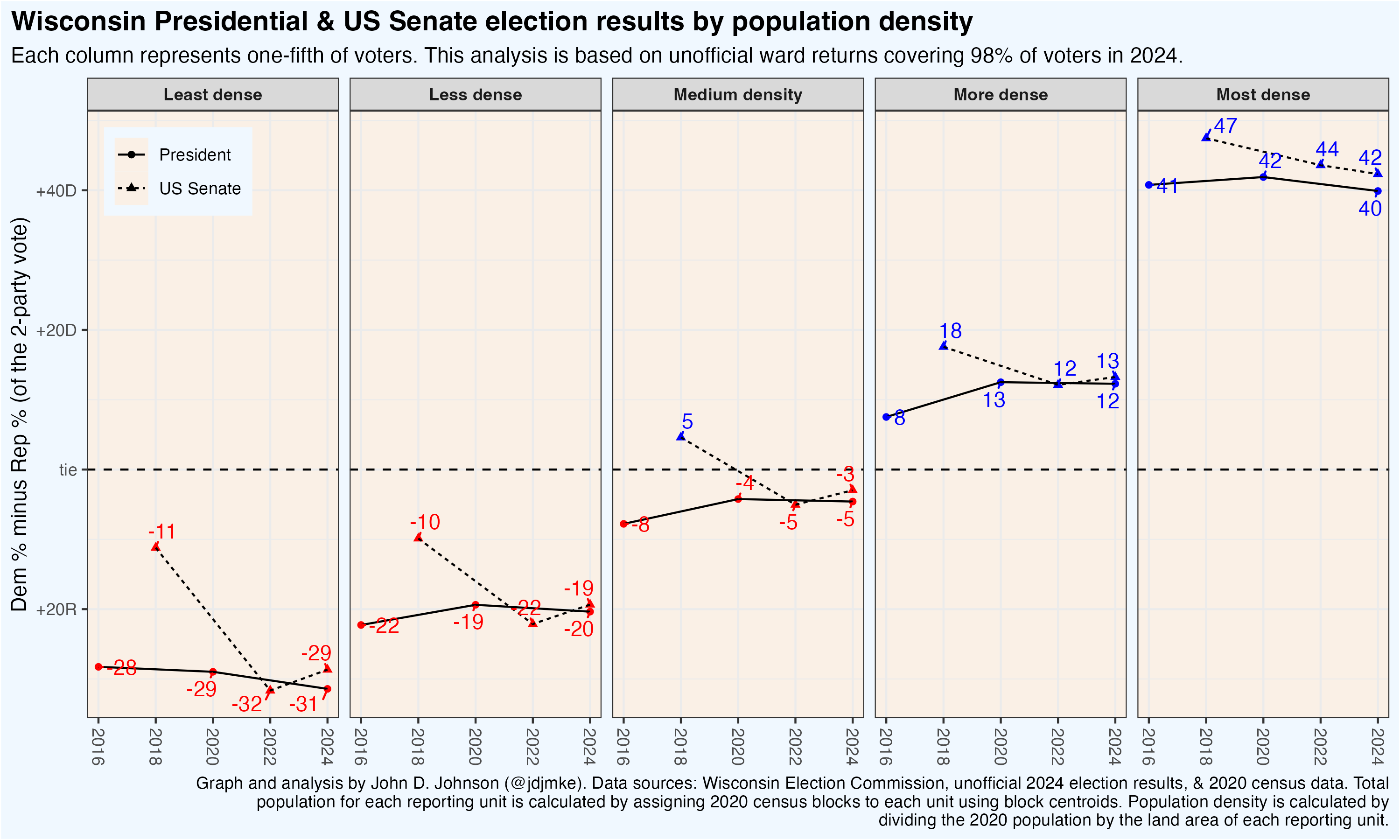

Population density

You can guess a lot about a ward’s political lean just by knowing how densely populated it is. But the gap between sparsely and densely populated places didn’t grow in 2024. Trump’s performance improved by a point or two in both the least and most dense places.

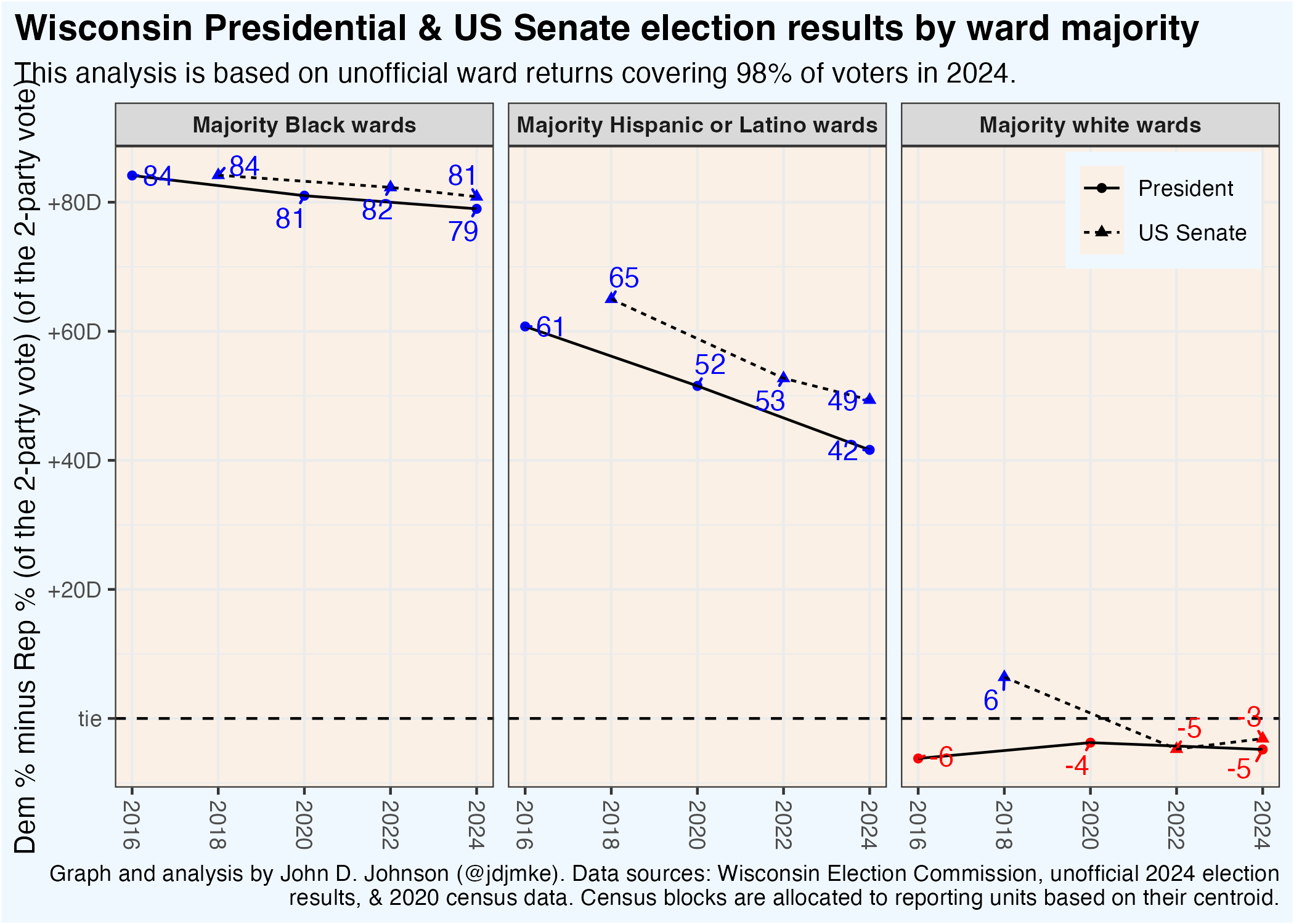

Race/ethnicity

Wisconsin doesn’t collect race in its voter registration data, so, to make this graph, I aggregated 2020 census block data into ward boundaries. By my count, there are 153 majority Black wards, 53 majority Hispanic/Latino wards, and 3,063 majority (non-Hispanic) white wards.

Taken as a whole, the majority white wards lean slightly Republican. Trump’s 2024 vote share fell halfway between his 2016 and 2020 performance. Baldwin’s vote share fell 9 points from 2018, but improved by 2 points over Mandela Barnes’ 2022 senate run.

In the majority Black wards, the Democratic vote share remains very high but has slipped by 1-3 points in each of the past elections.

The big change is in the relatively small set of majority Hispanic wards. The Democratic margin of victory fell from 61 points in 2016 to 52 in 2020 and 42 in 2024.

This sort of correlation runs the risk of the ecological fallacy, but the patterns here are consistent with trends in other cities and survey data.

Income

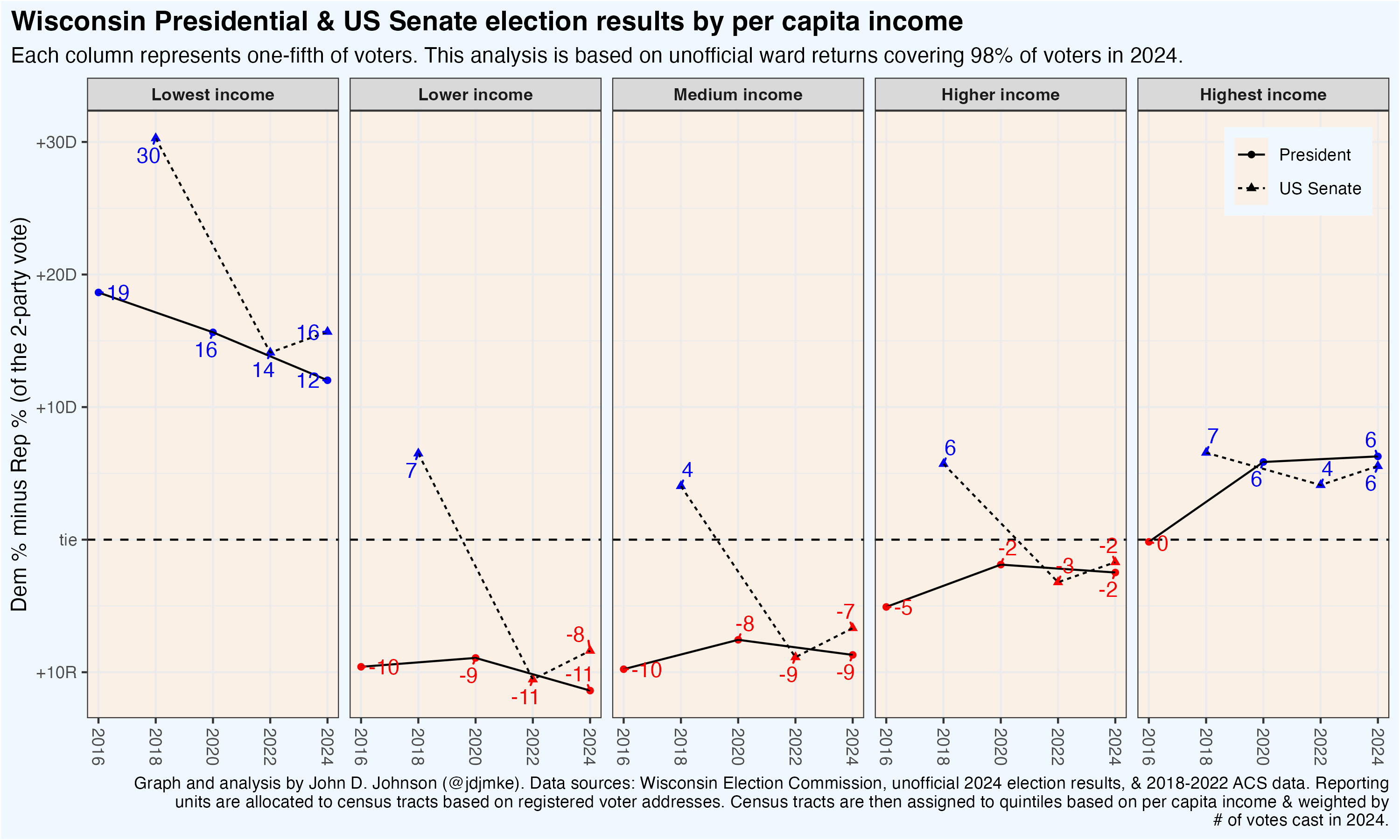

My final graph is possibly the strangest out of this set. It shows partisan support by per capita income, with the poorest wards on the left and the wealthiest on the right.

It is exactly these two kinds of places that are the base of the Democratic party. Democrats are strongest in the poorest fifth of wards, followed by the wealthiest fifth. Lately, Republicans have won everything in between.

Setting aside their baseline level of support, this graph also shows which places are growing more or less enthusiastic about the parties. Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton tied in the wealthiest fifth of wards in 2016. Biden and Harris each won them by 6 points.

Meanwhile, the Democratic margin of victory in the poorest fifth of wards slid from 19 points in 2016 to 16 in 2020 and 12 in 2024.

About this data

Throughout this article I use “wards” to refer to what are technically “reporting units.” In Wisconsin, municipal clerks in small towns are allowed, under certain circumstances, to combine multiple wards into larger reporting units. This reduces administrative load and helps protect voter privacy.

Ward data is published on election night by most county clerks, but it is not collected and standardized by the Wisconsin Election Commission for several weeks following each general election. Lacking data on the state’s 3,500-odd wards, most election analysis relies on the totals from Wisconsin’s 72 counties—a limitation which makes analysis like the above impossible.

To fill this gap, I have collected and standardized ward-level returns for the Presidential and US Senate race in (currently) 69/72 counties, covering 98% of voters. You can download a GEOJSON file with these ward boundaries, unofficial 2024 election results, and disaggregated past election results from 2012-2022.

Special thanks to Anna Balliekova, Charles Ruleis, Mitchell Henke, Charles Franklin, Marybeth McGinnis, Ben Welden, Kevin Goldfarb, Alex Ballwanz, Ben Iberle, and Dwight Maynor for their help tracking down ward files on election night.