Milwaukee’s Baby Bust Hit New Lows in 2025

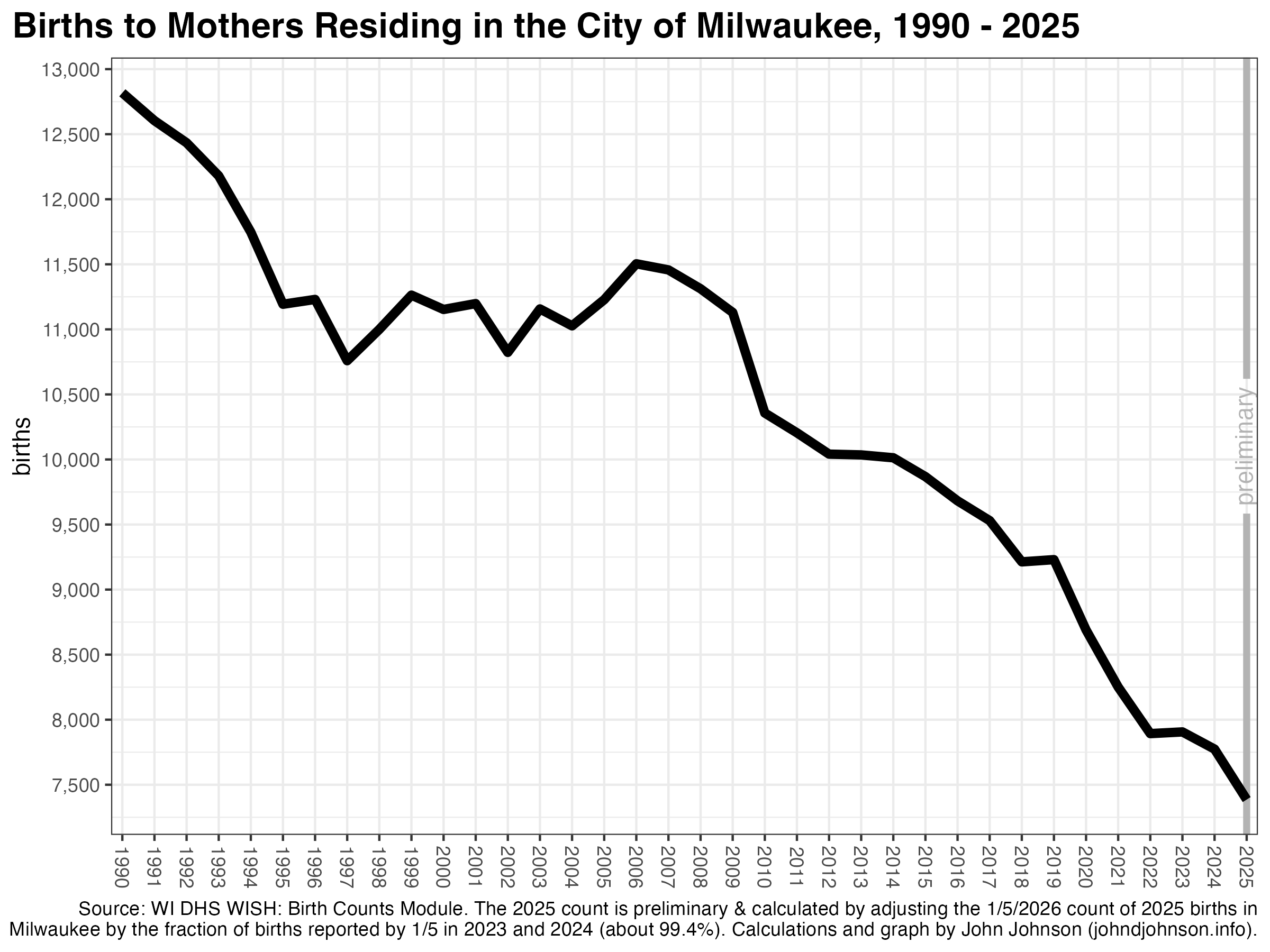

The fewest babies on record were born to Milwaukee mothers in 2025, according to preliminary vital statistics records.

As of January 5th, the state’s vital statistics database shows 7,343 Milwaukee births in 2025. Based on the reporting pattern in previous years, I estimate that the total number of 2025 births will stand at about 7,386 after the last records trickle in.[i]

This is a 5.0% decline from 2024, when 7,774 babies were born to Milwaukee moms. It is a 15.0% decline since 2020 and a 28.7% decline since 2010.

Births are only one component of population puzzle. Each year, people of all ages move both in and out of Milwaukee. But the number of births is the first ingredient of our future population, and the number of babies born has ripple effects in every following year. For example, in a response (at least partly) to declining demand, one large Milwaukee hospital stopped delivering babies altogether in 2022.

The drop in births throughout the 2010s also explains why Milwaukee’s population loss in the 2020 census was so surprising. The 2020 census came in well below what projections based on administrative data predicted. Those projections used birth and death records collected at the county level, and they estimated the county’s overall population accurately. The problem was that the Census Bureau model allocated births to each municipality based on patterns from the 2010 census, when, in fact, the share of babies born in the suburbs grew, relative to the city: a fact independently confirmed by both the 2020 census and local vital statistics.[ii]

Birth counts quickly affect school enrollments. Milwaukee’s births actually remained steady—even growing a bit—between the late 1990s and the late 2000s. This had a stabilizing effect on school enrollments, benefiting each sector of the city’s fragmented school system. There were actually more first graders attending a Milwaukee school in the 2014-15 school year than in 2005-06.

Then enrollment began to fall. The Great Recession, accompanied by an extreme mortgage foreclosure crisis in Milwaukee, coincided with a sharp drop in births. Newborn counts fell from 11,457 in 2007 to 9,213 in 2018. By 2023-24, there were 1,500 fewer first graders attending a Milwaukee school than in 2014-15.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, births dropped by 14.5% from 2019 to 2022. This was nearly three times the statewide decline of 5.1% over this period, so the drop in Milwaukee likely reflects prospective parents leaving the city in addition to couples putting off having a kid. Supporting this, census data shows a net outflow of 15,800 people leaving Milwaukee in the year ending July 1, 2021. Things improved after that, and net migration actually turned slightly positive in the year ending July 1, 2024, when the city gained about 500 residents in this way.

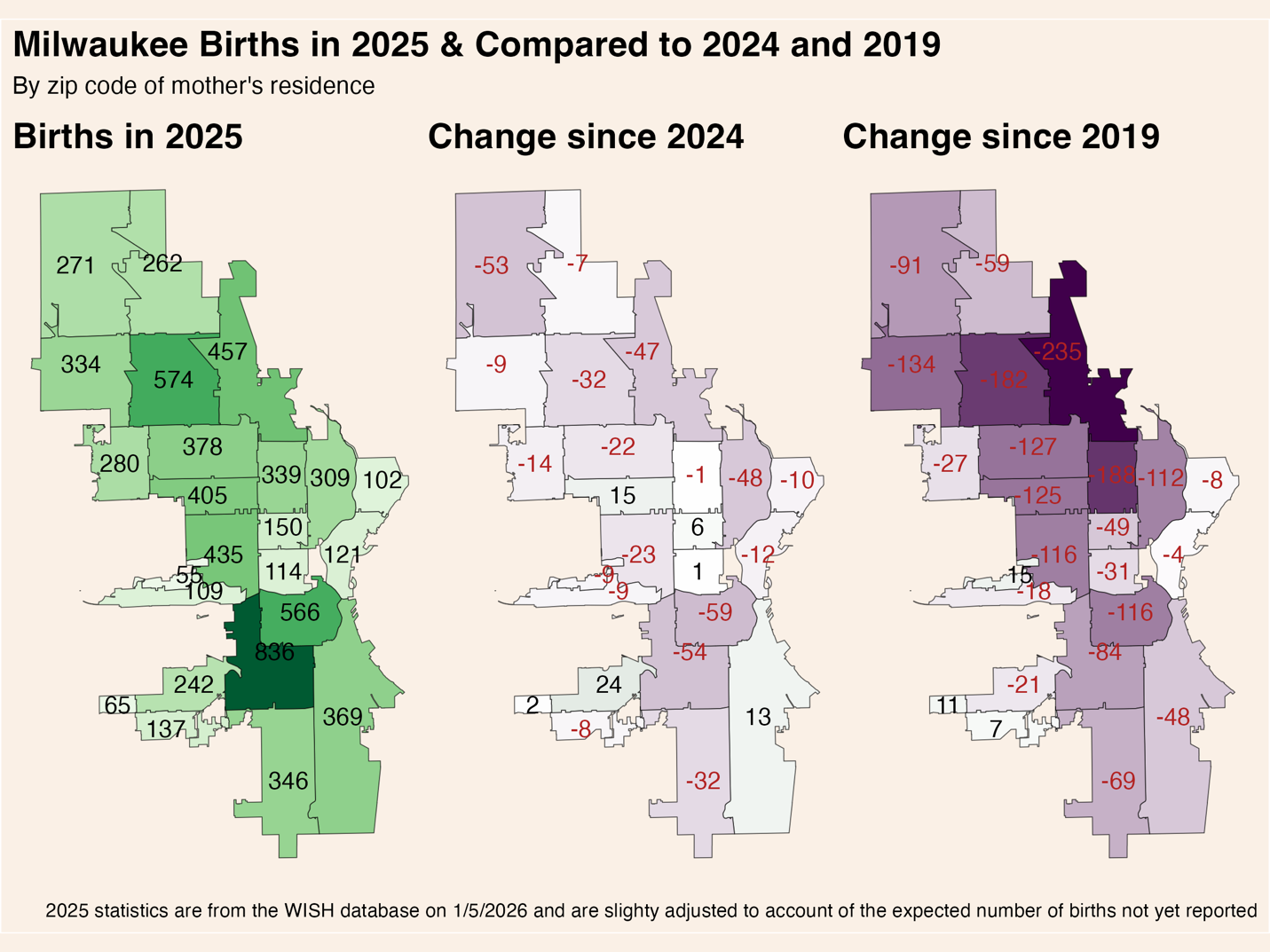

Mirroring this net migration pattern, births fell most sharply in the calendar years 2020 and 2021, before remaining more stable in 2023 and 2024. The renewed sharp drop in 2025 may indicate a resumption of negative net migration for the city or changes to the age profile and childbearing preferences of existing residents. Some hints might be gleaned from the map of where births have fallen in Milwaukee.

These three maps show, from left to right, the total number of babies born in each City of Milwaukee zip code during 2025, the change from 2024 to 2025, and the change from 2019 to 2025.

The cumulative effect of Milwaukee’s years-long run of declining births is large. As we begin 2026, 39,210 babies were born in Milwaukee over the past 5 years. At the beginning of 2020, that number was 46,345. Here are some final thoughts:

- There is no sign that Milwaukee’s baby bust has bottomed out. Two years ago, I thought it might have, but the latest data points toward continued declines of several hundred babies each year.

- Schools across all sectors will face declining enrollment for the foreseeable future, with each cohort likely being smaller than the last.

- While it is true that fertility rates are declining nearly everywhere, I think the rapidity (and location) of Milwaukee’s baby bust points to out-migration of prospective parents as a large factor. Much of this could be solved if more young couples felt Milwaukee was a good place to raise a family. In general, in Milwaukee’s healthiest and safest neighborhoods, the baby bust is either small or not happening at all.

[i] In the last couple years, a little over half of one percent of birth records were still outstanding by the following January 5th.

[ii] The Census Bureau Population Estimates Program uses vital statistics and modeled migration data to estimate county-level population. It then allocated the county-level population into municipalities based on the number of housing units in each (another tracked metric) and the average household size in the previous decennial census. In Milwaukee, the city’s average household size actually fell from 2.5 in 2010 to 2.39 in 2020, while in the Milwaukee County suburbs, the average household size stayed about the same.