If You Build It . . .

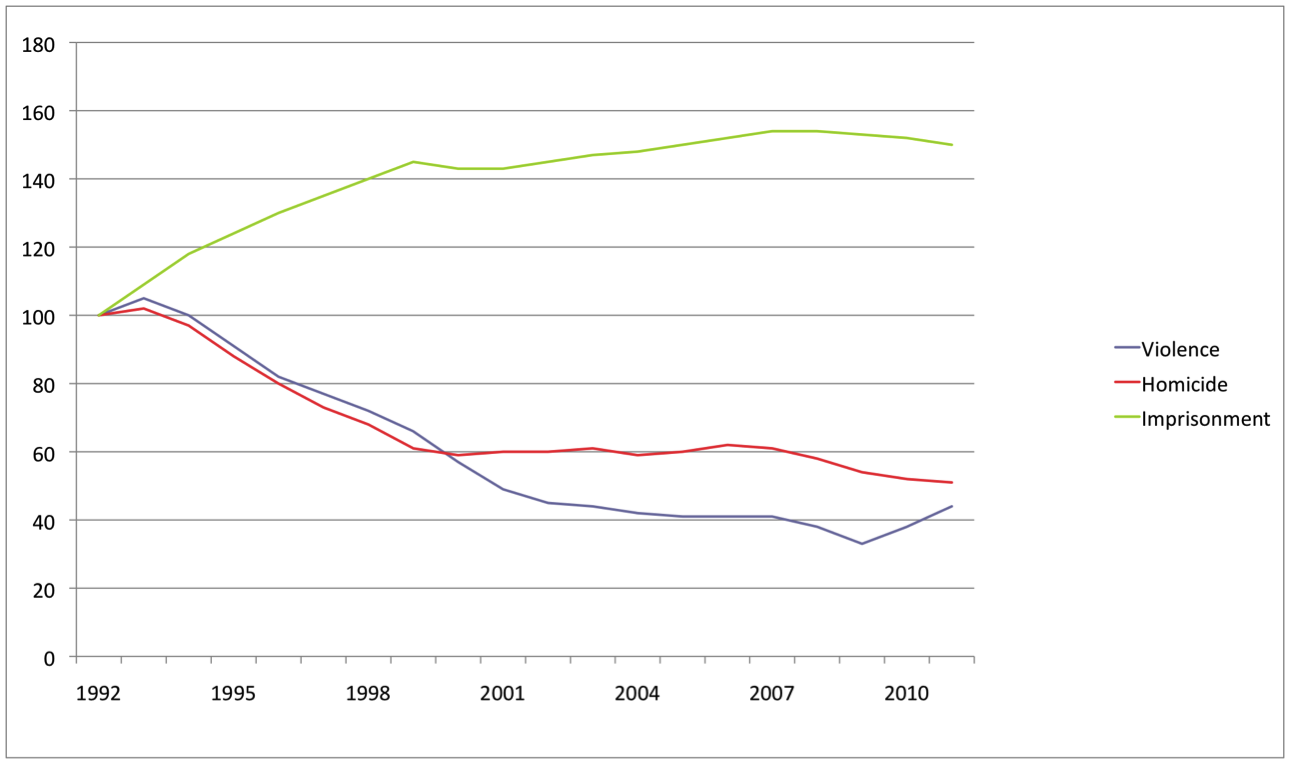

The paths followed by crime and incarceration in the United States have been mirror images of one another over the past two decades. This can be clearly seen in the graph below, which I prepared for an upcoming conference presentation.

The graph depicts year-by-year rates of imprisonment, homicide, and violent crime (the latter based on results from the National Crime Victimization Survey), indexed to 1992 rates. The mirroring effect is most pronounced if you compare imprisonment (green line) with homicide (red): between 1993 and 1999, imprisonment goes up at almost precisely the same rate that homicide goes down; in 2000, there is an abrupt leveling off in both areas; and neither has seen a lot of change since. The violent victimization line (blue) mostly tracks the homicide line, save for an additional three years of rapid decline (1999-2002) and a notable uptick between 2009 and 2011.

The mirror-image paths might seem counterintuitive. Shouldn’t less crime translate into less imprisonment? Let me suggest three theories to account for what has happened.