News reports indicate that President Obama will soon announce how he plans to use Executive Orders to implement some aspects of Immigration Reform, due to the failure of Congress to address the subject legislatively. I recently had the opportunity to participate in a program on Immigration Reform at the Law School on November 5, 2014, along with Stuart Anderson, the Executive Director of the National Foundation for American Policy and an Adjunct Scholar at the Cato Institute. The event was sponsored by the Law School Chapter of the Federalist Society, the Marquette Immigration Law Association, and the International Law Society. I want to thank Mr. Anderson for sharing his insights with the law students. Interested readers can click here to find a recent article by Mr. Anderson. What follows are my prepared remarks.

News reports indicate that President Obama will soon announce how he plans to use Executive Orders to implement some aspects of Immigration Reform, due to the failure of Congress to address the subject legislatively. I recently had the opportunity to participate in a program on Immigration Reform at the Law School on November 5, 2014, along with Stuart Anderson, the Executive Director of the National Foundation for American Policy and an Adjunct Scholar at the Cato Institute. The event was sponsored by the Law School Chapter of the Federalist Society, the Marquette Immigration Law Association, and the International Law Society. I want to thank Mr. Anderson for sharing his insights with the law students. Interested readers can click here to find a recent article by Mr. Anderson. What follows are my prepared remarks.

I have a daughter who is turning 21 next month. When a child reaches that age, parents start to ask themselves questions. Will my daughter bring someone home with her one day, and announce that she is engaged? How will I react if the person she brings home belongs to a different faith? How will I react if he is of a different race? How will I react if “he” is a “she?”

These are questions that tap into deep emotions, even if my rational brain tells me that the answers to these questions don’t matter. I know that my response to such a situation should be compassionate, and loving, and focus on my daughter’s happiness. But I also know that I may feel threatened or hurt or disappointed, without consciously wanting to. Maybe part of the problem is that I can’t control who my daughter brings home. To a certain extent, who becomes a member of my family is her choice, not mine.

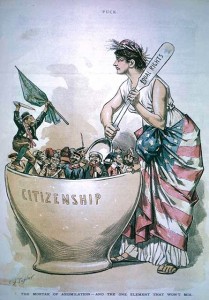

Immigration is about membership in our national family. It raises the same deep emotions that marriage raises within the family. And just as we can’t always choose who our children will marry, we also can’t always control who joins our national family. And Immigration policy needs to be rational, data-driven, and compassionate, and not based on knee jerk emotions.

Simple answers to complex social and economic problems don’t work. One challenge we face as a nation is that we share a longstanding geographic connection with Mexico. U.S. employers have turned to Mexican citizens for seasonal labor needs for a very long time. People have established migration patterns that persist through generations of the same family. These behaviors won’t change just because we tell people to stop. We need to address the underlying incentives and motivations for these behaviors.

Simple solutions can be counter-productive. We have spent billions of dollars on building a fence and militarizing our border with Mexico. But we forgot something basic. Fences don’t just keep people out. Fences also keep people in.

One type of fence is created by the law. In 1996, Congress passed a law creating 3 and 10 year bars for legal immigrants. Even if an applicant qualifies for a visa to come to this country lawfully, they are barred from receiving a visa for 3 years if the applicant was unlawfully present previously in the U.S. for six months, and barred from receiving a visa for 10 years if the applicant was unlawfully present for 1 year or longer. The intent was to create an incentive for undocumented aliens inside the U.S., many of whom were in the U.S. illegally while they waited for visa applications to be processed, to leave the U.S. in order to avoid the time penalty imposed by the law.

Rather than leave the U.S. and be separated from their family while waiting years for their visa priority date, many undocumented aliens choose to remain in the U.S. in an undocumented status. The law discourages those who are unlawfully present from seeking to obtain a visa to stay in the U.S. legally. That is because in order to receive such a visa, the alien would have to leave the U.S., thus triggering the 3 and 10 year bars and preventing re-entry into the United States for a long time.

In addition to laws that keep undocumented persons in the U.S., the militarization of the border makes the border crossing so dangerous that – once inside – people do not want to risk another crossing. Unlawful migration used to be temporary. The male head of the household would go to the U.S. to work for a few years and save money. Then they would return to Mexico and their family for a few years. If the U.S. economy was bad, and jobs were scarce, they would leave. Now more people who successfully navigate the border crossing decide to stay permanently. And they send for their families to join them in the United States, rather than having their families remain behind. And these unlawful entrants remain even if the U.S. economy is bad, which amplifies the impact of a recession on citizens and lawful immigrants.

Meanwhile, the militarization of the border leads to more deaths of those seeking to enter the United States. It has increased the fees that smugglers (or “coyotes”) can demand for helping these entrants make a border crossing. In fact, human smuggling has become such a lucrative business, as a result of the militarization of the border, that it has attracted heavily armed drug gangs to pursue this line of work, which has created greater risk for border enforcement officers.

Advocates for Immigration Reform recognize that our current system for legal immigration is part of the problem. Pouring more money into the enforcement of a system that ignores the reasons for human behavior will not solve anything. The law itself has to change.

Legal means of entry need to be created that would allow U.S. employers to hire immigrants in order to perform low skill labor. There is no realistic way for workers to get lawful visas to perform low skill labor under the current law, and therefore employers and undocumented workers ignore the law. This situation is exemplified by the dilemma faced by family dairy farms in Wisconsin. The work is difficult and the hours are long. The children of the farmers go to college and don’t want to return to work on the farm. The small towns nearby don’t have a big enough labor pool to provide sufficient native born workers. As a result, today the dairy industry in Wisconsin is heavily dependent on undocumented workers. Tour a dairy farm up North, as I have, and you’ll hear more Spanish being spoken than you’ll hear on the South Side of Milwaukee.

Critics of Immigration Reform say that creating visas for low skilled laborers will hurt U.S. workers and taxpayers. It will not. Immigrant labor in the United States is largely complementary to domestic labor. Immigrants tend to come in at a skill level higher than the domestic population (holders of advanced degrees) and lower than the domestic population (persons with less than a high school education). Therefore, immigrant labor does not typically compete for the same jobs as native born workers.

The best economic evidence we have indicates that the impact of immigration on the wages of native born workers is slight, with the possible exception of African American high school dropouts who may see their wages reduced by 3-10% due to immigrant competition. This data is confirmed by studies which show that states with high immigration levels do not have higher unemployment rates for native born workers than neighboring states with lower levels of immigration. (While U.S. workers are not harmed by immigration on a net basis, there are some segments of the native born population that are adversely affected and these segments should receive the focus of government job training efforts).

Lawful immigration for low skill workers also opens opportunities for native born workers to advance in salary. Companies that can profitably add more low skill workers, such as in the construction and landscaping fields, will create more supervisory positions to manage that workforce. Domestic workers will move up to take those positions.

The creation of more lawful immigrant workers, both through the addition of visas for low skill workers and the legalization of undocumented workers already here, will not adversely affect the social safety net or increase our taxes. Lawful immigrants are a “free generation” when it comes to government benefits. They are ineligible to receive most federal and state benefits until they have first worked lawfully in the United States for ten years. And they do not have parents in the United States who are receiving social security or Medicare payments. So they make substantial financial contributions into the system before anyone in their family receives any financial benefit. (The primary exception is that their children will likely attend public schools).

Not only does Immigration Reform make sense, the alternatives to reform are unacceptable. If we do nothing, we allow upwards of 10 million people to remain in an undocumented status, living in fear of deportation and subject to exploitation. We will also continue to throw tax dollars at symbolic but largely ineffective attempts to seal off the border. Meanwhile, undocumented workers will continue to enter the U.S. freely. This is because approximately 40% of all undocumented workers cross the U.S. border lawfully using temporary tourist or work visas, and then remain in the U.S. when those visas expire.

Deporting those undocumented workers who are already here is simply not feasible. It would take a massive expenditure of money and resources to locate and process 10 million persons, and it would lead to the large scale separation of families. This is because a large proportion of undocumented workers belong to blended families where some family members are citizens, some are lawful immigrants, and some are undocumented.

It is also fanciful to expect U.S. employers in industries like agriculture, landscaping, and hotel/restaurant services to be able to quickly replace undocumented workers with native born workers. The economic impact of mass deportations on these companies would be significant. Native born workers would demand higher salaries than immigrant workers, and these companies can’t pay money that they don’t have. It is also misguided to believe that companies can turn to technology to do the job of undocumented workers. Many crops ripen at different rates in the field and therefore cannot be harvested by a machine. And I have yet to see the machine that can make a hotel bed.

The argument in favor of Immigration Reform recognizes that there are forces changing our lives that can’t be stopped by wishful thinking or by simple commandments to “obey the law.” These forces include the evolution of the U.S. economy away from manufacturing and towards high tech and service industries, the ever-decreasing cost of international transportation (we live on a shrinking planet), and the manner in which the internet lowers information costs about foreign destinations (allowing potential immigrants to arrange for potential jobs and living arrangements before leaving their home country, thus reducing the risk of immigrating).

We can’t reverse these changes. However, these changes can be managed so as to decrease the disruption that they cause on human lives. In order to do so, we need to adopt national policies that avoid demonizing people or dividing human beings into “us” and “them.” We also need to avoid false appeals to national security or jingoism. Rhetoric designed to stir our emotions has proven effective in rousing public opinion against Immigration Reform, but it does nothing to solve the problem that we face as a country.

There are reports that following Republican gains in the mid-term elections, business groups will once again attempt to get Congress to act on Immigration Reform. Prior legislative efforts failed when opponents used charges of “amnesty” and “terrorism” to whip up opposition among conservative Tea Party groups. This caused legislation to stall because it raised the prospect that Republican representatives who voted for reform might face a primary challenge from the Right.

Only by reforming our immigration laws can we successfully moderate the effect of changing societal forces, and simultaneously keep the impact of that change from being disproportionately borne by certain categories of workers or disproportionately borne by certain geographic segments of the country.

Immigration policy is not the only area where it is important to advocate policy responses that are based on data (rather than politically popular slogans) and where the focus of our efforts should be on reducing the negative impact of these broader societal changes on human beings (rather than placing corporate or political interests ahead of real people). There are other challenges that we face as a nation where complex forces are acting to change our society and a national response is called for: rising health care costs, climate change, and concerns over sustainable energy. How we respond to these challenges says a great deal about our capacity for democratic self-government.

This is no lomger about immigration. It is about the checks and balances in the constitution. Congress has the power to override a Presidential veto. The President does not have the authority to create or change a law without it being passed by Congress.

I hope that he signs the Executive Order. That will increase the chances that Ted Cruz will be President in 1/2017.

What would that mean? Try this for starters:

1) Rand Paul, Vice President

2) Grover Norquist, Secretary of Treasury

3) Scott Walker, Secretary of Labor

4) Jan Brewer or Rick Perry, INS

5) Stanley McCrystal, Veteran’s Administration