Today, the Senate Majority Leader, Mitch McConnell, announced the unprecedented decision that the United States Senate will refuse to consider any nominee put forward by President Obama during the remainder of his term in office to fill the current vacancy on the United States Supreme Court. Senator McConnell said, “My decision is that I don’t think that we should have a hearing. We should let the next president pick the Supreme Court justice.”

Today, the Senate Majority Leader, Mitch McConnell, announced the unprecedented decision that the United States Senate will refuse to consider any nominee put forward by President Obama during the remainder of his term in office to fill the current vacancy on the United States Supreme Court. Senator McConnell said, “My decision is that I don’t think that we should have a hearing. We should let the next president pick the Supreme Court justice.”

The refusal of the United States Senate to consider any nominee put forth by President Obama is a clear violation of the Appointments Clause of the United States Constitution. Under the Appointments Clause (Article II, Section 2, Clause 2):

The President . . . shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law. . .

The role of the President is to appoint nominees to the United States Supreme Court. The role of the Senate is to provide their “advice and consent” to the President on the specific nominee.

The meaning is “advice and consent” is clear and uncontroversial. The Framers of the Constitution recognized that absolute monarchs such as the King of England had abused the power to appoint public officials. This abuse was due to the monarch’s absolute power to appoint anyone they chose. In response, the Constitution divided the power to appoint superior public officials and Supreme Court Justices between the Executive (the President) and the Senate. The Framers of the Constitution diffused the appointment power, just as they diffused several other powers among separate branches of the federal government in order to guard against abuse.

However, the separation of the power to appoint into two pieces is not split 50-50 between the President and the Senate. Rather, the split is made between the President’s absolute power to select any nominee he or she chooses, and the Senate’s power to accept or reject the nominee. The intent of the Appointments Clause is to give the Senate a check on the President’s choice, in order to prevent nominations that result from corruption, cronyism, or the advancement of unqualified nominees (i.e., family members). The Appointments Clause does not give the Senate any role in deciding who or when the President will nominate.

In fact, the Senate has no pre-nomination role at all in the appointment process. The Senate’s only role under the Constitution arises after the President makes a nomination. In this regard, it has often been remarked that the power of initiative lies with the President under the Appointments Clause.

Scholars across the political spectrum agree on this understanding of the Appointments Clause and the meaning of “advice and consent.” For example, an excellent explanation of the Appointments Clause is presented by Northwestern University Law School Professor John O. McGinnis, a prominent conservative scholar, on the website of the Heritage Foundation. His analysis, written in 2005, is worth quoting at length:

Both the debates among the Framers and subsequent practice confirm that the President has plenary power to nominate. He is not obliged to take advice from the Senate on the identity of those he will nominate, nor does the Congress have authority to set qualifications for principal officers. The Senate possesses the plenary authority to reject or confirm the nominee, although its weaker structural position means that it is likely to confirm most nominees, absent compelling reasons to reject them.

The very grammar of the clause is telling: the act of nomination is separated from the act of appointment by a comma and a conjunction. Only the latter act is qualified by the phrase “advice and consent.” Furthermore, it is not at all anomalous to use the word advice with respect to the action of the Senate in confirming an appointment. The Senate’s consent is advisory because confirmation does not bind the President to commission and empower the confirmed nominee. Instead, after receiving the Senate’s advice and consent, the President may deliberate again before appointing the nominee.

The purpose of dividing the act of nomination from that of appointment also refutes the permissibility of any statutory restriction on the individuals the President may nominate. The principal concern of the Framers regarding the Appointments Clause, as in many of the other separation of powers provisions of the Constitution, was to ensure accountability while avoiding tyranny. Hence, following the suggestion of Nathaniel Gorham of New Hampshire and the example of the Massachusetts Constitution drafted by John Adams, the Framers gave the power of nomination to the President so that the initiative of choice would be a single individual’s responsibility but provided the check of advice and consent to forestall the possibility of abuse of this power. Gouverneur Morris described the advantages of this multistage process: “As the President was to nominate, there would be responsibility, and as the Senate was to concur, there would be security.”

The Federalist similarly understands the power of nomination to be an exclusively presidential prerogative. In fact, Alexander Hamilton answered critics who would have preferred the whole power of appointment to be lodged in the President by asserting that the assignment of the power of nomination to the President alone assures sufficient accountability:

“[I]t is easy to show that every advantage to be expected from such an arrangement would, in substance, be derived from the power of nomination which is proposed to be conferred upon him; while several disadvantages which might attend the absolute power of appointment in the hands of that officer would be avoided. In the act of nomination, his judgment alone would be exercised; and as it would be his sole duty to point out the man who, with the approbation of the Senate, should fill an office, his responsibility would be as complete as if he were to make the final appointment.” The Federalist No. 76.Chief Justice John Marshall in Marbury v. Madison, Justice Joseph Story in his Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, and the modern Supreme Court in Edmond v. United States (1997) all confirm that understanding.

. . . .

The practice of the first President and Senate supported the construction of the Appointments Clause that reserves the act of nomination exclusively to the President. In requesting confirmation of his first nominee, President Washington sent the Senate this message: “I nominate William Short, Esquire, and request your advice on the propriety of appointing him.” The Senate then notified the President of Short’s confirmation, which showed that they too regarded “advice” as a postnomination rather than a prenomination function: “Resolved, that the President of the United States be informed, that the Senate advise and consent to his appointment of William Short Esquire. . . .” The Senate has continued to use this formulation to the present day. Washington wrote in his diary that Thomas Jefferson and John Jay agreed with him that the Senate’s powers “extend no farther than to an approbation or disapprobation of the person nominated by the President, all the rest being Executive and vested in the President by the Constitution.” Washington’s construction of the Appointments Clause has been embraced by his successors. Some Presidents have consulted with key Senators and a few with the Senate leadership, but they have done so out of comity or political prudence and never with the understanding that they were constitutionally obliged to do so. A law setting qualifications would not only invade the power of the President, it would also undermine the authority of the Senate as the sole authority to decide whether a principal officer should be confirmed.

(Italicized emphasis in this extended quote is mine and not in the original)

By refusing to consider any nominee put forth by President Obama for the remainder of his term, the Senate is exceeding its constitutional power by effectively asserting the authority to initiate or not initiate the nomination process. This asserted power goes far beyond any authority for the Senate contained in the Appointments Clause. Moreover, by asserting the power to foreclose an appointment before a nomination is made, the Senate is attempting to exercise a pre-nomination power rather than a post-nomination reaction to the President’s nominee. In so doing, the Senate is asserting a role in the nomination process that has absolutely no basis in the text of the Constitution.

Ironically, Wisconsin is currently represented in the Senate by Senator Ron Johnson, who has consistently and stridently attacked President Obama on the basis that the Obama Administration is exceeding its constitutional authority in implementing the Affordable Care Act or in issuing Executive Orders relating to immigration enforcement. Senator Johnson even took the unusual step as a sitting Senator of suing the Obama Administration in federal court for exceeding its powers. Given the announcement today by Senator McConnell, one wonders whether Senator Johnson will see fit to condemn the unconstitutional power grab taking place within his very own House of Congress.

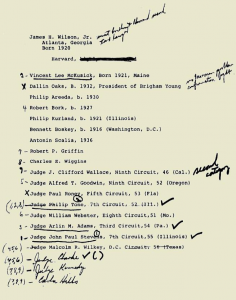

Photo: List of potential Supreme Court nominees with handwritten notations by President Gerald Ford.

I am not a lawyer. However, it seems to me that the President can ask the Supreme Court to determine if the Senate’s refusal to act on his nominee is a violation of the constitution. If it is a violation, can the court then issue an order forcing the Senate to act?

Mr. Hurwitz:

This is not an issue for the federal courts to decide for two reasons. First, no one person is suffering a particularized injury due to the violation of the Constitution. We are all suffering equally. Therefore, there is not a plaintiff with standing to bring a court challenge. Second, this is a classic dispute between two branches of the federal government, of the kind that the Supreme Court has usually found to constitute a non-justiciable political question. The remedy that is available for the actions of the Senate is for the general public to call and email their Senators and demand that they perform their constitutional duty.

Polling Data reveals that the general public strongly supports Senate consideration of a nominee, including in Wisconsin:

http://www.publicpolicypolling.com/main/2016/02/kelly-ayotte-ron-johnson-hurt-reelection-prospects-with-supreme-court-stance.html

The sitting President should nominate a new justice as is his duty.

The remedy you suggest, that–“the general public call and email their Senators and demand that they perform their constitutional duty”–does that ever actually work? With the exception of Sen. McCaskill, every letter I’ve ever sent to my elected officials has been either ignored or responded to with a standard form letter, “thanks for writing, your concerns are important, bla bla bla..” without ever addressing the specific subject of my letter. I’m wondering if they would pay more attention to an on-line petition directed to the entire Senate as a group? If the number of voters signing on to the petition, nationwide, was high enough to make it “newsworthy”, do you think that might have more impact?

I am curious about the formulation of the “advice and consent” provided by the Senate. The mechanics of it (send a letter in response to the President with the “Resolved, ” phrasing), is not spelled out in the constitution, but is accepted as tradition. Could a president, having NOT received a response from the Senate in a reasonable amount of time, with the caveat that there are no national emergencies (war, pandemic) that would justify a delay, declare that the Senate’s silence be interpreted as their consent to the nomination? Then that will in the future help establish an acceptable limit to the timeframe within which the Senate could act?