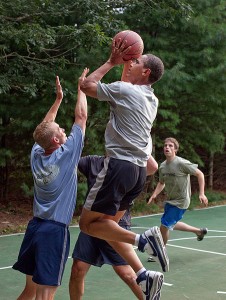

A “head fake” is a basketball move where the player holding the ball feints as if starting a jump shot, but never leaves his feet. Done correctly, it causes the defender to jump off of their feet in anticipation of the shot, arms flailing helplessly. Meanwhile, the shooter calmly resets and scores a basket while the defender is harmlessly suspended in the air.

A “head fake” is a basketball move where the player holding the ball feints as if starting a jump shot, but never leaves his feet. Done correctly, it causes the defender to jump off of their feet in anticipation of the shot, arms flailing helplessly. Meanwhile, the shooter calmly resets and scores a basket while the defender is harmlessly suspended in the air.

Just over two weeks ago, the mid-term elections supposedly signaled the end of President Obama’s ability to drive the policy agenda in Washington. Last Thursday night, the nation’s “Basketball Player in Chief” executed a brilliant head fake on immigration policy, disproving this conventional wisdom. Hints that the President intended to “go big” and use his executive authority to conduct an overhaul of the Immigration and Nationality Act had generated anticipatory paroxysms of outrage by Republicans, who hit the airwaves with charges of constitutional violations and threats of impeachment. However, the executive actions that the President actually announced last Thursday were more modest in scope than what Latino groups and reform advocates wanted, and far less provocative than congressional Republicans feared.

The executive actions on immigration fall well within the Executive Branch’s established authority to set priorities in the enforcement of Immigration Law and clearly within the constitutional power of the President. Meanwhile, the President’s Republican critics have already committed themselves to a campaign of outrage and indignation, even though it is increasingly evident that they lack a legal basis to attack the President’s actions or a political strategy to undo them. The President’s head fake is evident when the details of the Executive Orders are examined.

Last week, President Obama announced several executive actions relating to immigration enforcement, including the following:

1. He directed the Department of Homeland Security (DHA) to extend deferred action (a form of temporary relief from removal from the United States) to the parents of children who are either United States citizens or Lawful Permanent Residents, provided that the parents have resided continuously in the United States since before 2010 and do not present a risk to either public safety or national security. “Deferred action” is a form of relief that currently exists under the immigration laws. It does not legalize anyone, and it does not create a path to citizenship or lawful status. If granted, however, it provides that removal proceedings will not normally be initiated against the recipient for a set period of years (3 years in this case, renewable at the discretion of DHA) and it permits the issuance of work authorization upon a showing of economic need. It is estimated that approximately 4 million persons presently in the United States in undocumented status will be eligible to apply for deferred action status under this program.

2. He directed the Department of Homeland Security to eliminate the age cap for applications by “Dreamers,” persons who were brought to the United States by their parents when they were children. Under the program adopted in 2012, known as “Deferred Action Childhood Admissions” (DACA), young people who entered the U.S. when they were children are eligible for relief from removal if they were born after 1981 and entered the U.S. before June 15, 2007. Last Thursday, the President directed DHA to expand the DACA program so that anyone who entered the U.S. before January 1, 2010 can apply, regardless of their current age, so long as they entered the U.S. when they were a child. DACA status is good for three years and is renewable at the discretion of DHA. It does not create legal status and it does not create a path to citizenship. It is estimated that the elimination of the age cap will make approximately 270,000 additional persons eligible for the program. It is worth noting that the undocumented parents of individuals who receive DACA status do not receive any benefits under either DACA or the other executive actions announced by the President, because Dreamers are not U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents.

3. He ended the Secure Communities program that had resulted in deportations of individuals arrested by law enforcement on the basis of misdemeanors or traffic violations and he directed DHS to focus its deportation efforts instead on the removal of aliens who present threats to national security, public safety or border security. DHS officials can continue to initiate removal proceedings against aliens who do not fall within these categories where DHS determines that the removal of the alien “would serve an important federal interest.”

The President has justified these orders as an exercise of his prosecutorial discretion to enforce the Immigration and Nationality Act. The nature of the Executive Branch’s prosecutorial discretion was described by the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Arizona v. United States as follows:

Congress has specified which aliens may be removed from the United States and the procedures for doing so. Aliens may be removed if they were inadmissible at the time of entry, have been convicted of certain crimes, or meet other criteria set by federal law. Removal is a civil, not criminal, matter. A principal feature of the removal system is the broad discretion exercised by immigration officials. Federal officials, as an initial matter, must decide whether it makes sense to pursue removal at all. If removal proceedings commence, aliens may seek asylum and other discretionary relief allowing them to remain in the country or at least to leave without formal removal.

Discretion in the enforcement of immigration law embraces immediate human concerns. Unauthorized workers trying to support their families, for example, likely pose less danger than alien smugglers or aliens who commit a serious crime. The equities of an individual case may turn on many factors, including whether the alien has children born in the United States, long ties to the community, or a record of distinguished military service. Some discretionary decisions involve policy choices that bear on this Nation’s international relations. Returning an alien to his own country may be deemed inappropriate even where he has committed a removable offense or fails to meet the criteria for admission. The foreign state maybe mired in civil war, complicit in political persecution, or enduring conditions that create a real risk that the alien or his family will be harmed upon return. The dynamic nature of relations with other countries requires the Executive Branch to ensure that enforcement policies are consistent with this Nation’s foreign policy with respect to these and other realities.

Where does this power to exercise prosecutorial discretion come from? It is a necessary component of the administration of justice by the Executive Branch, with antecedents in the English common law, and it is constitutionally located in the Take Care Clause of Article II Section 3 of the Constitution (“[H]e shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed . . .” ). Thus, when Congress charged the Department of Homeland Security with “[e]stablishing national immigration enforcement policies and priorities” (6 U.S.C. Section 202(5)), Congress was necessarily granting the Executive Branch the discretion to choose among multiple alternative priorities in immigration enforcement and to enforce the law in order to advance one or more priorities over others.

There are limits on the exercise of prosecutorial discretion, however. The Executive Branch cannot contravene express limits that Congress has placed over the exercise of its discretion. For example, if Congress declares that it is mandatory to place certain aliens in detention in advance of their removal hearing, the Executive Branch may not ignore that command in order to prioritize the detention of different aliens. In addition to respecting express limits placed on its discretionary actions by Congress, the Executive Branch cannot exercise discretion in such a way that the Executive Branch frustrates the congressional policy sought to be advanced under the statute. Finally, the Executive Branch is not free to completely abdicate its responsibilities under the statute, thereby leaving the law unenforced entirely.

The Executive Orders announced by President Obama do not contravene any of these limits. Congress has created multiple categories of aliens who are removable from the United States, but it has not set any express limitations on the ability of the Executive Branch to prioritize the removal of one category of removable alien over another. In particular, Congress has never indicated that aliens who are not a threat to public safety, and who have children lawfully entitled to remain in the United States, cannot have enforcement proceedings against them deferred indefinitely while other enforcement priorities are pursued.

Under President Obama, the United States has deported more aliens than under any other President in history. Removals are currently running at a level of more than 400,000 per year. The immigration courts, the detention centers, and the officers of the Department of Homeland Security are operating at full capacity under the resources that Congress has allocated, and yet the undocumented population in the United States continues to be estimated at over 10 million persons.

Under these circumstances, it is ludicrous to argue that President Obama’s decision to prioritize the removal of dangerous aliens somehow constitutes an abdication of Executive Branch responsibilities under the Immigration and Nationality Act, or that his orders somehow undermine the purpose of the statute. Devoting DHS resources to the pursuit and removal of Dreamers necessarily leaves less resources available for the pursuit and removal of violent felons. Maximizing the Executive Branch’s ability to deport the most dangerous categories of undocumented aliens is completely faithful to the purpose of the law.

The conclusion that President Obama acted within his constitutional authority is supported by several analyses. The Office of White House Counsel provided President Obama with a legal opinion supporting his authority. The Congressional Research Service provided members of Congress with a Legal Overview that explains the bases of the President’s power. Finally, a group of over 100 law professors who teach the subject of Immigration Law has released a letter expressing their judgment that the President has the power to take these actions under the Constitution.

All of these analyses include the discussion of prior instances where Presidents have exercised the discretionary authority to decline to remove aliens who had no legal basis to remain in the United States. This discretionary authority has taken several forms over the years, whether as deferred action, extended voluntary departure, or parole. While the form of discretionary relief has differed, all of these prior Executive Branch actions have operated to permit groups of otherwise inadmissible aliens to remain within the United States due to humanitarian concerns. For example, deferred action was used to permit foreign students to remain in the United States in 2005, after Hurricane Katrina closed several universities and the students were temporarily unable to meet the requirements of a student visa. Similarly, on well over a dozen occasions the Executive Branch has used the practice of extended voluntary departure to allow aliens of specified nationalities to remain in the United States regardless of their visa status so long as conditions in their home country made their return dangerous. Finally, Presidents have routinely used the parole power to permit waves of undocumented entrants to remain in the United States when they entered fleeing political unrest or a natural disaster.

Critics of President Obama’s actions on immigration have distinguished these past uses of discretionary enforcement by the Executive Branch, arguing that they only support the legitimacy of discretionary enforcement when the President acts on a case-by-case basis, or in instances effecting a small number of aliens, or in response to a temporary emergency. This criticism is misplaced. At one time or another, each of these types of discretionary relief has been used to provide relief from removal to large groups of aliens, and in response to ongoing conditions raising humanitarian concerns as opposed to temporary emergencies. For example, in 1990, President H.W. Bush used executive action to defer the removal of an estimated 1.5 million aliens who were the immediate family members of persons eligible for legalization under the 1986 immigration reform law (this number equaled roughly 40% of the then estimated undocumented population of 3.5 million persons in the United States).

History and practice often provide a context for determining whether the President possesses a power under the Constitution. However, past history does not create a power. It is important to recognize that neither the number of aliens impacted by previous executive actions nor the existence of a temporary emergency constitute the source of the President’s authority to defer the removal of aliens. Either the power to utilize discretion in the enforcement of congressional directives is a power delegated to the Executive Branch under the Take Care Clause of the Constitution or it is not.

Properly understood, the Immigration and Nationality Act is poorly structured. Congress exercises the authority to define the quality and number of aliens who qualify for lawful admission to the United States, on the front end of the admission process. However, on the back end of the process the President exercises the discretion to defer the removal of unqualified aliens, thus tacitly tolerating their continued presence in this country. Professors Adam Cox and Cristina Rodriguez call the statute “pathological” for operating in such a fashion. In their 2009 article “The President and Immigration Law,” they call for granting the Executive Branch more authority to determine admissions policies in the first instance, thus obviating the need for the Executive Branch to exercise as much discretion when it comes to deferrals of removal.

Since President Obama has acted within his constitutional authority, the real question is whether the use of his authority was politically astute. It certainly appears that it is. Republican legislators are in a box of their own making. They sit in safe gerrymandered districts, where the only risk they face at election time is a primary challenge from the right. Therefore, they dare not vote in favor of any Immigration Reform plan that includes the legalization of large numbers of undocumented workers.

Meanwhile, Republicans have sufficient numbers to pass legislation undoing the President’s executive orders. However, taking such legislative action would antagonize Latino voters and important Republican constituencies in the agricultural sector. In addition, President Obama would simply veto the legislation and Republicans do not have the votes to override such an action.

Finally, they cannot use the power of the purse to defund the implementation of the President’s orders. The operation of the division of United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), which is charged with implementing the President’s orders, is funded through application fees and not through congressional appropriations. Therefore, Congress can only retaliate indirectly against the President, by attacking unrelated programs or services.

The only obvious option open to Republicans is to continue to mold public opinion using conservative media and right wing think tanks, in order to create the false impression that President Obama’s orders are unconstitutional. Meanwhile, more thoughtful analyses have begun to emerge from the midst of the conservative hysteria. For example, writing in the Wall Street Journal today, William Galston expresses second thoughts on the President’s actions. While his initial response was a “visceral sense” that President Obama acted without constitutional authority, he now believes that President Obama acted within his constitutional power when issuing his executive orders. Perhaps, as more commentators look at the President’s actions objectively, and recognize that what the President actually did is far more modest in scope than the conservative reaction merits, pressure will build on Congress to do what it should have done years ago: reform the Immigration and Nationality Act.

My previous post on immigration reform can be read here.

On November 20, 2014 the President issued an Executive Order to grant deferred action, stay of deportation, to millions who qualify. This is exactly what Temporary Protected Status (TPS) offers to people from certain countries who are in the United States. This same protection was offered by several Presidents before him, under Section 244 of the immigration law. Undocumented aliens must prepare for their upcoming application(s), please inform them.

Unfortunately, the same people the President sought to help with the order are afraid to even prepare to apply before the immigration forms are issued. The USCIS website is telling the people to prepare gathering information before USCIS issues the form, but the immigrants are afraid because of what the Republicans and the news are saying out there.

There is NO Constitutional authority for executive orders, actions or signing statements. Executive actions, orders, and signing statements in effect change the law… which is legislating. The Constitution says that: ALL legislative power is vested in Congress…. ALL of it does not include giving a little to the President. You can say this is just a President seeing that the laws are faithfully executed… but you know it is not.

There is NO Constitutional Authority for Executive orders. You can not overcome the word “All”.

Recently, some observers have compared President Obama’s tactics as a basketball player to his governing style, thus underscoring the basketball analogy that I make in this post:

http://www.newyorker.com/news/sporting-scene/understanding-obama-through-basketball

http://www.politico.com/story/2015/12/democrats-back-obama-scotus-immigration-216430

Discretion is a necessary fact of life. There simply are too many laws for any instrument of government to enforce. As America has always been a nation of immigrants, I favor a less strict immigration/deportation policy.

In response to Mark Wright above (no relation), I feel his reading of the Constitution stopped a few words short. Article I states “All legislative powers HEREIN GRANTED (emphasis added)”. Congress does NOT have a monopoly on legislative power.