New Marquette Lawyer Sheds Light on Issues Shaping Today’s World

Marquette Lawyer is not a news magazine, strictly speaking. In fact, there is hardly anything left of news magazines in the United States. But that hardly means there isn’t a lot to learn about what is in the news. And the Summer 2025 issue of Marquette Lawyer certainly provides news in the sense of insights on several major current matters.

Marquette Lawyer is not a news magazine, strictly speaking. In fact, there is hardly anything left of news magazines in the United States. But that hardly means there isn’t a lot to learn about what is in the news. And the Summer 2025 issue of Marquette Lawyer certainly provides news in the sense of insights on several major current matters.

Start with Canada. No, we’re not interested in the controversies over making Canada part of the United States or trade policies between the two nations. But we are interested in understanding our neighbor to the north better, especially when it comes to its legal system, which is surely an appropriate focus for those involved in legal education and the law more generally.

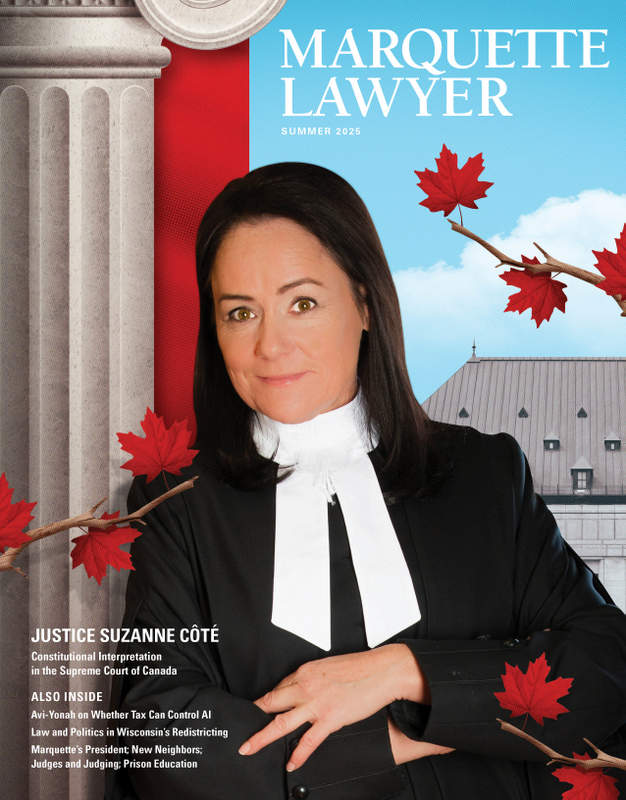

That’s what brought the Hon. Suzanne Côté, a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, to Marquette Law School to present the annual Hallows Lecture last academic year. “Roots of the Living Tree,” an edited version of her lecture, is the cover story of the magazine and offers insights into the premises and practices of Canadian constitutional law. The text may be read by clicking here.

While the Canadian legal system makes infrequent news in the United States, the rapidly developing world of artificial intelligence is in the news often. How to control problems connected to AI, such as false content known as “hallucinations” and copyright infringement, is a timely and important topic.

That brought Reuven Avi-Yonah, the Irwin I. Cohn Professor of Law and director of the International Tax LLM Program at the University of Michigan, here for the annual Robert F. Boden Lecture this past September. Avi-Yonah, one of the world’s most widely respected scholars on tax law, delivered a lecture, “Can Tax Policy Help Us Control Artificial Intelligence?” That became a major piece in this issue, which may be read by clicking here.

The way Wisconsin handles decisions about setting boundaries for legislative districts has attracted national attention recently. The ups and downs of redistricting decisions have been both influential in shaping power in Wisconsin politics and difficult to follow. John D. Johnson, a researcher with Marquette Law School’s Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education, is an expert on redistricting and what it has meant to Wisconsin politics. “The Boundaries of Law and Politics” is his richly detailed article describing the history of the subject. As redistricting continues to be in the news, Johnson’s guide to the subject provides valuable background. It may be read by clicking here.

Another issue that underlies much of the news in today’s world: the quality of judging and judges, from local courts to the highest courts in the land. “In Search of Humbler—and Wiser—Judgments” offers thoughts from Chad M. Oldfather, professor of law at Marquette University. Oldfather’s new book, Judges, Judging, and Judgment: Character, Wisdom, and Humility in a Polarized World, was published by Cambridge University Press. Oldfather also talks about good judgment in legal practice beyond the courtroom in this question-and-answer dialogue. It can be read by clicking here.

Marquette University’s new president, Kimo Ah Yun, has been in the news a lot. In a Lubar Center “Get to Know” program on January 17, 2025, Ah Yun told moderator Derek Mosley, director of the Lubar Center, and an audience of about 200 his powerful personal story, as well as some aspects of his vision for Marquette. The story of his “underdog” rise may be read by clicking here.

Over the years, ways to improve the outcomes of people being released from incarceration has been the subject of several programs at Marquette Law School. In December 2013, for example, Craig Steven Wilder, a professor of American history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was interviewed by Mike Gousha, distinguished fellow in law and public policy, about Wilder’s book on how race and slavery issues were handled by some prominent universities.

In the audience was R. L. McNeely, L’94, a retired professor at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. At a lunch afterwards for a small group, the conversation turned to Wilder’s involvement in a program aimed at helping educate incarcerated people.

McNeely followed up by starting to work on creating such a program in Wisconsin, involving Marquette and ultimately several other universities. It took years for the idea to become reality, and McNeely, who died in 2020, did not live long enough to see that happen. “From Conversation to Dream to Idea to Reality” describes the origins of the idea and the determination of McNeely and several others, including faculty in Marquette University’s Klingler College of Arts and Sciences, to launch what is now known as the McNeely Prison Education Consortium. The article may be read by clicking here.

“Good Neighbors”—that’s the headline on an article about changes in the immediate vicinity of Eckstein Hall, the Law School’s home. The changes include a new pastor at the Church of the Gesu, Rev. Michael Simone, S.J., and a largescale renovation of sections of the church building; the $42 million renovation and expansion of Straz Hall, making it the new home of the College of Nursing under the continued leadership of Dean Jill Guttormson; and the vision of a new director, John McKinnon, at the Haggerty Museum of Art. The Law School community welcomes all three good neighbors. The article may be read by clicking here.

In early 2025, John T. Chisholm stepped down after 18 years as Milwaukee County district attorney and more than three decades of service in the office and is now a senior lecturer at the Law School. In an essay, “A New Venue for Kindling the Fire for Lawyers to Serve Others,” Chisholm offers his perspective on his new role. It can be read by clicking here.

John Novotny recently retired after almost 20 years working on behalf of the Law School and longer service yet to Marquette University. In remarks at Novotny’s retirement reception, Law School Dean Joseph D. Kearney praised Novotny for more than his success in raising funds. Novotny embodies the vision of Jesuit education, Kearney said. The text of his remarks may be read by clicking here.

In his column, titled “Speaking Just for Myself,” Dean Kearney reflects on his approach to aspects of his office. His column may be read by clicking here.

Finally: the Class Notes describe recent accomplishments of more than 40 Marquette lawyers, including Byron B. Conway, L’02, who was recently sworn in as a federal judge serving the Green Bay Division of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin. The notes may be read by clicking here, and the back cover (here), through two examples, spotlights the impressive record of Marquette law students serving in pro bono and public service roles.

The full magazine may be read by clicking here for the PDF or here for the “interactive” version.

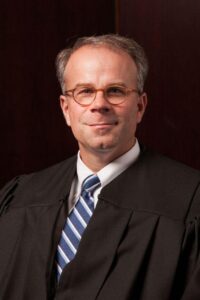

The Hon. Michael Y. Scudder, judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, delivered this year’s Hallows Lecture, yesterday evening, to more than 200 individuals in Eckstein Hall’s Lubar Center. The lecture was exemplary.

The Hon. Michael Y. Scudder, judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, delivered this year’s Hallows Lecture, yesterday evening, to more than 200 individuals in Eckstein Hall’s Lubar Center. The lecture was exemplary.