Students, would you like to make it easier for your professors to retain the information presented in your typed assignments, papers, briefs, and tests?

Students, would you like to make it easier for your professors to retain the information presented in your typed assignments, papers, briefs, and tests?

Professors, would like to retain more of the information that your students are presenting to you in their typed assignments, papers, briefs, and tests?

Then please read what the Seventh Circuit has to say about its “Requirements and Suggestions for Typography in Briefs and Other Papers.”

For starters, “[t]ypographic decisions should be made for a purpose. The Times of London chose the typeface Times New Roman to serve an audience looking for a quick read. Lawyers don’t want their audience to read fast and throw the document away; they want to maximize retention.”

Students don’t want their audience (professors) to read fast and throw the document away either. Maybe the fallback format requirements of “15 pages, double-spaced, Times New Roman, one inch margins” shouldn’t be the fallback? What else does the Seventh Circuit have to say about our old friend Times New Roman?

Professional typographers avoid using Times New Roman for book-length (or brief-length) documents. This face was designed for newspapers, which are printed in narrow columns, and has a small x-height in order to squeeze extra characters into the narrow space. Type with a small x-height functions well in columns that contain just a few words, but not when columns are wide (as in briefs and other legal papers). In the days before Rule 32, when briefs had page limits rather than word limits, a typeface such as Times New Roman enabled lawyers to shoehorn more argument into a brief. Now that only words count, however, everyone gains from a more legible typeface, even if that means extra pages.

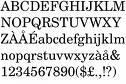

So what typeface should we be using? The Seventh Circuit recommends a “proportionally spaced type.” What’s proportionally spaced type, you ask? “Proportionally spaced type uses different widths for different characters. . . . A monospaced face, by contrast, uses the same width for each character.”

Additionally the Seventh Circuit recommends “typefaces that were designed for books.” And what typefaces were designed for books? The obvious ones are the ones with “book” somewhere in the name. Examples of typefaces designed for books include “New Baskerville, Book Antiqua, Calisto, Century, Century Schoolbook, and Bookman Old Style.” Furthermore, “faces in the Bookman and Century families are preferable to faces in the Garamond and Times families.”

And what was that about Rule 32 and word limits instead of page limits? Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 32(a)(7) allows principal briefs to exceed 30 pages if the brief “contains no more than 14,000 words” when the brief is accompanied by a certification by the attorney that the brief complies with the word limit.

I just checked my briefs and memos from my 1L Legal Writing classes and all of them were turned in with Times New Roman as the typeface and with a page limit. Maybe format requirements have changed in the two years since I took those classes. I know for a fact that some professors have gotten rid of the fallback format requirements. In my Copyright Seminar this semester, Professor Boyden’s format requirements mirror the Seventh Circuit’s recommendations: a proportionally spaced typeface and both a word limit and a page limit.

Instead of relying on the fallback format requirements, professors should allow students to use typeface selection to their advantage. A choice in typeface selection won’t be the difference between an A and a C, but, as the Seventh Circuit explains, “[y]ou can improve your chances by making your briefs typographically superior. It won’t make your arguments better, but it will ensure that judges grasp and retain your points with less struggle. That’s a valuable advantage, which you should seize.”

Here’s an interesting consideration – will your reader be reading a printed version or on a computer screen (or the new stepchild of both, a Kindle)? The federal system, with it’s electronic filing, makes it difficult to determine.

Why does it matter? Your average laser printer prints at 1200 DPI (dots per inch). Your average 15″ laptop screen has around that many pixels across its entire width. Many fonts are hard to read in electronic format but easier on paper.

Here’s an interesting question – with page limits out the window, and times new roman designed for narrow columns, is there any rule stopping creative lawyers from submitting either (a) dual-columned briefs (like reading a Lexis or Westlaw printout) or (b) single-columned briefs with 3″ margins?

Interesting question about dual columns. I don’t see a federal rule that specifically prohibits it. But there is a FRAP rule that briefs have to be double-spaced, which would look weird in dual column format. Also, under the main federal rules, the font has to be 14 (!) points — a misguided effort to deal with TNR’s narrowness. The 7th Circuit fortunately has pruned that down to 12 points.

There are some circuits that I think still permit book-binding (e.g. the 2nd, when I was there), so if you can swing the expense, that would look the best.

Finding the perfect font seems to be a hot topic in the legibility and readability of text – especially with the growth of reading text in digital format. This website provides a nice little summary of the recent research: http://www.unc.edu/~jkullama/inls181/final/serif.html. Tom brings up a good point: There seems to be a difference when a reader reads text in print as opposed to in digital format.

Another and related issue may be the use of different fonts between parties’ legal documents of the same case. As part of my old job, I designed project maps, mainly for oil and gas companies. The science of mapping has always been extremely conscious of fonts used to label various map elements (e.g., rivers always in a small, italicized, serif font; color-matched and following the curve of the waterway). This partly stemmed from enhancing the legibility and readability of maps, but it also arose out of a need for standards. Certainly, those two considerations are not independent of one another. Because project planning at my past job often involved a series of maps—like one map containing environmental data and one containing land ownership data—it was important to have standard fonts between the various maps so that the “reader” could effectively comprehend the common elements of the various maps.

Applying that to the legal world, I believe standardizing fonts between parties’ legal documents would not enhance only the legibility and readability of the individual documents, but the legibility and readability between the documents. The Seventh Circuit has recommended a number of different fonts to use, but I wonder if courts should develop even more stringent standards for font use.

I really enjoyed this post. As I told my class, I’m going to break out of my Times New Roman requirement and allow a broader array of fonts for future assignments.

For additional reading on this topic, I would recommend Ruth Anne Robins, Painting with Print: Incorporating Concepts of Typographic & Layout Design Into the Text of Legal Writing Documents, 2 J. Ass’n legal Writing Directors 108 (2004) and Maria Perez Crist, E-Brief: Legal Writing for an Online World, 33 N.M. L. Rev. 49 (2003).

I think that what you might want to do is “brand” yourself with a consistent text/heading combination. That will imprint your documents with your own ethos. Law firms have intuitively done this kind of branding and I recommend it when I speak at CLE’s (of course, I recommend that law firms choose a readable/strategic combo). So, my students know that my handouts will be in my own combo of Century School Book/Arial Narrow (boldfaced). I have had a few students mention to me a year or so ago that when certain documents were sent out under the signature of the faculty they could tell that I was a primary author because of the fonts. Now, whether or not that was considered a good or bad thing I am not sure…

Ruth Anne Robbins

p.s. I love this blog!

A comment from one who regularly must read (both on paper and on screen) briefs and other documents prepared by lawyers. Fonts DO make a difference. Times is abysmal. Century Schoolbook/New Century Schoolbook looks as good on screen as it does on paper. Very easy to read, especially longer documents. White space is a significant ‘readability’ factor. For an excellent discussion of this topic take a look at Typography for Lawyers by Matthew Butterick.