Baseball’s antitrust exemption, first recognized in the United States Supreme Court’s 1922 Federal Baseball Club v. National League decision and affirmed most recently by Congress in the Curt Flood Act (1998), is a well-known feature of Major League Baseball’s history. However, historians of baseball and sports law scholars have devoted very little time to exploring the consequences of the exemption. They have rarely asked how the baseball industry might have developed differently had it been subject to the Sherman and Clayton Acts.

Baseball’s antitrust exemption, first recognized in the United States Supreme Court’s 1922 Federal Baseball Club v. National League decision and affirmed most recently by Congress in the Curt Flood Act (1998), is a well-known feature of Major League Baseball’s history. However, historians of baseball and sports law scholars have devoted very little time to exploring the consequences of the exemption. They have rarely asked how the baseball industry might have developed differently had it been subject to the Sherman and Clayton Acts.

This essay looks at one aspect of this question by examining the effort of American League team owners in 1939 to bring the powerful New York Yankees back to the field by restricting the ability of the perennial champions to engage in player transactions with other league teams.

THE NO TRADING WITH THE YANKEES RULE

Although the New York Yankees have been the most dominant major league team since the early 1920’s, at no point in their history were they any more dominant than in the years 1936 to 1939. After finishing in second place for three straight seasons (1933-1935), the Yankees returned to the top of the American League heap in 1936 behind the stellar play of 21-year old rookie outfielder Joe DiMaggio, first baseman Lou Gehrig, and catcher Bill Dickey. (Babe Ruth played his last season with the Yankees in 1934.)

The 1936 team, considered by some historians as the greatest team in Major League history, won 102 games while losing only 51, scored 1065 runs, and finished 19.5 games ahead a second-place Detroit team that featured future Hall-of-Famers Mickey Cochrane, Charlie Gehringer, Goose Goslin, Hank Greenberg, and Milwaukeean Al Simmons. In the World Series, the men in pin-stripes outscored their cross-Bronx rivals the New York Giants by a margin of 43 runs to 23, while winning the series in six games.

The following year, the Yankees’ record actually improved to 103-51, besting runner-up Detroit by 13 games and vanquishing the Giants in the World Series for the second year in a row, this time by a margin of four games to one. 1938 saw a similar result, even though the Yankee record “declined” to 99-53. This time they finished 9.5 games ahead of the rejuvenated Boston Red Sox before trouncing the Chicago Cubs, four games to none, in the World Series.

In 1939, the Yankees had one of their greatest seasons ever, winning 106 games while losing only 45. Even though the runner-up Red Sox increased their win total from 1938, they now finished a distant 17 games off the pace. In the World Series, the Yankees again triumphed in four straight games, disposing of the Cincinnati Reds by a combined score of 20-8.

The Yankee success in 1939 was even more remarkable, given that legendary first baseman Lou Gehrig played only eight games that year before retiring as his body began to succumb to the disease that now bears his name. Although the Iron Horse’s presence was obviously missed, his absence from the line-up had little effect on the potent Yankee offense, which totaled a major league leading 967 runs.

In addition to their success on the field, the Yankees also led the American League in attendance over the four-year period, topping the AL in 1936, 1938, and 1939, and finishing second to Detroit in 1937. In 1936 and 1938, they led all of organized baseball in total attendance.

By the end of the 1939 season, the other American League teams had begun to despair of ever catching the Yankees, and several owners were willing to entertain the idea that changes in the league operating rules were necessary to bring the Yankees back to the pack. The effort was led by Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith who proposed a number of new regulations designed to make it more difficult for the Yankees to repeat as champions.

Most of Griffith’s proposals were deemed too radical by his fellow owners, but the League did adopt his proposal for a new rule, effective immediately, that prohibited teams from trading or selling players to the previous league champion unless the players involved in the deal had first been placed on waivers (which would allow other league teams to claim them for $7,500). Conceding the inevitable, the Yankees did not oppose this restriction, and the measure passed unanimously. The next day’s Chicago Tribune described the action with the headline, “League Curbs Yankees”; the New York Times labeled it “baseball’s first radical legislation.” (Chicago Tribune, December 8, 1939, p. 35; NYT, December 8, 1939, p. 38.)

Because existing rules required that American League players be placed on intra-league waivers before they could be traded or sold to teams in the National League, the new rule meant that the Yankees could acquire players from other major league teams only after every other American League team decided that they did not want the player at the waiver price, effectively reducing the supply of established players available to the Yankees.

The “no trading with the pennant winner” rule was also submitted to the National League owners, but the senior circuit magnates declined to adopt it. No team had dominated the NL for very long in the 1930’s, and four teams—the Cubs, Giants, Cardinals and Reds—had won pennants in that decade.

While most members of the Yankee juggernaut of the late 1930’s were home grown or had been acquired from minor league teams, a handful, mostly pitchers, had been acquired in trades with other American League teams. The Yankees’ everyday stars — outfielders Joe DiMaggio, Charlie “King Kong” Keller, and George Selkirk, infielders Red Rolfe, Frankie Crosetti, and Joe Gordon, and catcher Bill Dickey — had either been signed originally by the Yankees as amateurs or else, like DiMaggio, purchased from independent minor league teams.

Only first baseman Babe Dahlgren, Gehrig’s replacement, had been acquired from another major league team, and he hardly qualified as a star. Dahlgren had been purchased from the Boston Red Sox in February 1937, but then spent most of the next two seasons in the minor leagues before cracking the Yankee line-up in 1939, when Gehrig abruptly retired. That year he batted a weak .235 with only 15 home runs and regularly filled the 8th spot in the Yankee line-up. After another mediocre season in 1940, he was essentially given away to the National League’s Boston Braves.

Of the top Yankee reserves, only outfielder Jake Powell had come from another team, and he had been acquired in a mid-season trade with Washington in 1936 in exchange for outfielder Ben Chapman, who had widely been viewed as a better player than Powell but who had ended up in Yankee manager Joe McCarthy’s doghouse.

In contrast to the everyday starters, a significant portion of the Yankee pitching staff in 1939 had been acquired from other American League teams, albeit over the course of several years. Four of the team’s six starting pitchers had become Yankees by this method.

Mound ace Red Ruffing had been acquired in a trade with the Red Sox during the 1930 season, and starters Monte Pearson and Bump Hadley had come over in 1935 in trades with Cleveland and Washington, respectively. The most recent acquisition had been Oral Hildebrand who was traded by the St. Louis Browns to the Yankees in October of 1938, for two untested players. At the time of the rule’s adoption in December 1939, much of the press coverage reported that the rule had been prompted by the ease with which New York had acquired Hildebrand, who went 10-4 in 1939, from the last-place Browns.

The “outrage” over the acquisition of the 32-year old Hildebrand had a certain “after the fact” quality. Hildebrand was an established major league pitcher in the fall of 1938, but he was hardly thought of as one of the premier pitchers in baseball. He had gone 8-10 with a 5.69 ERA for the 7th place St. Louis Browns in 1938, and while he was one of the Browns’ better pitchers, there is little evidence of protest on the part of other American League clubs at the time of the trade that brought him to New York.

The same was true for the other Yankee pick-ups. Monte Pearson had gone 8-13 with a 4.90 ERA in his final season with Cleveland, while Bump Hadley had compiled a stat line of 10-15 and 4.93 with the Senators the year before he became a Yankee. Even Red Ruffing was just 0-3 with a 6.38 ERA with Boston when he was acquired by the Yankees in 1930.

The Yankees were hardly buying up the American League’s best pitchers. At worst, they were just very good at identifying underperforming pitchers on other teams who would flourish with the Yankee line-up behind them. Nevertheless, they were winning with ease, and their opponents were desperately looking for a way to stop them.

In 1939, it was actually the runner-up Boston Red Sox, not the Yankees, that had been built through intra-league player acquisitions, as wealthy new owner Tom Yawkey abandoned even the pretense of making a profit. The core of the 1939 Red Sox team had been acquired from other American League teams, usually by cash purchase, and included a stable of already well-established stars like future hall-of-famers Joe Cronin, Jimmie Foxx, and Lefty Grove, star outfielders Doc Cramer and Joe Vosmik, and pitchers Elden Auker and Danny Galehouse.

SHERMAN ACT IMPLICATIONS

The “no trading with the pennant winner” certainly looks like an unreasonable restraint of trade. A lack of concern on the part of the Yankees regarding the detrimental effects of the rule probably muted the question, but could the Yankees have challenged the “no trading” rule as a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act had they desired to do so?

While the Supreme Court’s 1922 ruling that organized baseball was not subject to the antitrust laws had not been overturned, by the end of 1939, the Court had dramatically expanded the scope of the antitrust laws through an expansive interpretation of the meaning of the Constitution’s Commerce Clause.

Had the Court revisited the issue of baseball and interstate commerce in 1941 or 1942 (when an appeal would likely have reached the court), would it have overruled Federal Baseball? While we can never know for sure what the answer would have been, it seems likely that the justices who delivered the opinion in Wickard v. Filburn (1941) would have found organized baseball to constitute a form of interstate commerce.

For example, in 1940, U. S. Attorney General Thurmond Arnold took the position that the business of screening motion pictures in theaters was a form of interstate commerce, and the motion picture studios, entities somewhat analogous to sports leagues, accepted the legitimacy of this characterization. (This position was confirmed by the Supreme Court after World War II in United States v. Paramount Pictures (1948).) While it is true that the Supreme Court confirmed baseball’s antitrust exemption in 1953, only four of the justices who decided that case were on the Court in 1941, and one of the four, Stanley Reed, dissented in that case, and another, Felix Frankfurter, indicated that he would have decided the question differently had it arisen a decade earlier.

Of course, no lawsuit of this type was forthcoming in 1939 or 1940. There were a number of reasons for this. First of all, had the litigation-averse American League owners believed that the Yankees might have sued them on antitrust grounds, that would almost surely have been enough to dissuade them from adopting the “no trading with the pennant winner” rule in the first place.

More importantly, it would hardly have been in the interests of the Yankees to raise the issue of the validity of the baseball antitrust exemption in 1939 or 1940, even if they believed that they would be harmed by the new rule.

In 1939, no team benefitted more from organized baseball’s mesh of anti-competition rules than the New York Yankees. For example, the principal of territorial exclusivity — that existing teams had a monopoly over their local markets — meant that the Yankees did not have to worry about sharing the enormous New York market with any other American League team or with any other National or minor league team, other than the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers with whom they had shared the country’s largest metropolitan area since 1903. In an era where ticket sales and concessions were the primary generators of revenue, the New York teams controlled a market whose populations was almost three times larger than the second largest market (Chicago), which was shared by two teams and more than 14 times the size of the smallest market (Cincinnati).

Similarly, the reserve system — under which teams in organized baseball agreed not to offer contracts to players on other teams, even after their contracts expired, unless their previous team agreed to release them — also greatly worked to the Yankees benefit. The reserve system prevented the Yankees from having to worry about wealthy owners like Boston’s Tom Yawkey signing New York players to contracts, but allowed the equally well-off Yankees to purchase players from other teams , if they chose to do so. By depressing player salaries, the reserve system allowed wealthier teams to devote financial resources to acquiring new players rather than to retaining existing ones.

Moreover, the reserve system applied to minor league players as well, and minor league salaries were subject to a strict salary cap. These features allowed the cash-rich Yankees to outbid other teams for amateur players which they could then stash away in their large farm system while waiting for them to develop. In 1939, the Yankees had the largest minor league system in the American League and the second largest in major league baseball. (Only the St. Louis Cardinals, the originators of the farm system concept, operated a larger farm system.) Although minor league players under contract were eventually available to other major league teams through the minor league draft, manipulation of the draft eligibility rules allowed the Yankees to hold on to their best minor league prospects until the team determined if they had major league potential. Lesser players could be sold to other teams to recoup part of the costs of operating the farm system.

Consequently, the Yankees had little reason to contemplate any action that might undermine the existing market restrictions of professional baseball. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that when the question of the continued viability of the Federal Baseball holding finally came before the Supreme Court in 1953, it did so in a case in which the New York Yankees were not the plaintiff, but the defendant. The plaintiff in Toolson v. New York Yankees was a Yankee minor league player who challenged the legality of the reserve system.

If for some reason baseball’s antitrust immunity had been overturned in the early 1940’s, the question of whether the “No trading with the Yankees rule” would have constituted an illegal group boycott under the Sherman Act in 1940 is a complicated one. There are no sports-related antitrust decisions at all before the mid-1950’s, and few before the 1970’s, so it is difficult to know how pre-World War II courts would have treated a professional sports league for antitrust purposes. Would, for example, the single entity defense have been asserted that early? Would such restraints have been viewed as acceptable under the rule of reason, or would they have been viewed as per se violations? While it is tempting to answer these questions in the affirmative, the one lesson from the history of sports antitrust law is that judicial behavior in sports cases is extremely difficult to predict.

THE SUBSEQUENT FATE OF THE NO TRADING RULE

Somewhat surprisingly, the “no trading with the pennant winner” rule actually appeared to accomplish its purpose in 1940, as the Yankees failed to repeat as league champions.

The New Yorkers got off to an extremely poor start in 1940, and on May 23, resided in the American League cellar with a record of 11-17, 8.5 games behind first-place Boston. The team’s play improved during the next month, but losses were still almost as frequent as wins, and as late as June 26, the team still had a losing record.

Although several Yankee regulars got off to slow starts at the plate, the primary problem in the early going in 1940 was a shortage of effective pitching. Ruffing and Pearson pitched well, although limited run support allowed Ruffing to win only four of his first eleven starts. However, the rest of the staff was in shambles. Number 2 starter Lefty Gomez injured his arm in his first start of the season, and was not able to pitch again until July. Bump Hadley apparently started the season with a sore arm, and after one start in late April spent the rest of the season in the bullpen where he pitched ineffectively. Oral Hildebrand also entered the season with arm problems and did not appear in a game until May 4. Although he pitched well in short appearances, he was available only for 9 appearances before being sold to the minor leagues at the end of July (which ended his major league career). Spud Chandler, who had missed most of the 1939 season because of injuries, was inserted into the starting rotation in late April, and while Chandler would end his major league career with 109 wins and the highest winning percentage in baseball history, he lost three of his first four starts in 1940, twice getting knocked out of the box before the fifth inning.

Clearly the Yankees were in need of pitching help during the first three months of the 1940 season, but thanks to the American League’s “no trading” rule, they were unable to obtain any new players from their competitors. An obvious source of help would have been the perennially cash-strapped Philadelphia Athletics and St. Louis Browns, who had kept themselves financially afloat during the 1930’s by regularly selling their best players to other American League teams.

By the end of June, the New York ship was re-righted, as effective replacement pitchers were found in the team’s bullpen and minor league system. From June 27 on, the Yankees had the highest winning percentage in the American League, and while they were able to overtake the Red Sox, their record was not quite good enough to catch Detroit and Cleveland, who finished two and one games, respectively, ahead of the Bombers. Although the Yankees ended the season winning 10 of their last 12 games, losses to lowly Washington and Philadelphia in the last three days of the season prevented them for tying Detroit for first place. According to the New York Times, it was the “no trading” rule that “unquestionably prevented a fifth straight pennant for the Yankees.” (NYT, July 8, 1941, p. 22.)

With the Yankees’ early season slump, the American League in 1940 featured a new competitive balance that created a much more exciting season. In the end, Detroit edged Cleveland for the pennant by a single game, clinching the title in a season-ending series between the two teams. The Yankees finished third, followed by Boston and Chicago, both of whom had winning records. The Red Sox had been the early season leaders and had remained in contention for the title into September. The White Sox, like the Yankees, had started slowly, but had pulled themselves into the pennant race in August. Although they subsequently stumbled, the team rebounded to finish on a high note. The St. Louis Browns escaped the cellar for the lofty heights of 6th place. The Senators had little to boast about, but they were clearly less horrible than the Philadelphia Athletics. Every team in the American League, including the Yankees, drew more fans in 1940 than they had in 1939.

One might have thought that the success of the 1940 season would have led to the permanent enshrinement of the “no trading with the defending champion” rule. However, with the Yankees dethroned, there was an effort immediately after the 1940 World Series to repeal the “no trading” rule, which now applied to the new pennant winners, the Detroit Tigers. Not surprisingly, Detroit and New York supported the repeal, but five of the six remaining teams voted to keep the restriction in place, at least for the 1941 season.

Although Detroit had won the American League pennant in 1940, its older line-up limped into the off-season. Nagging injuries had required all-star second baseman Charlie Gehringer to miss a number of games during the regular season and had clearly limited his performance in the World Series (where he batted a weak .214). In December 1940, the conventional wisdom was that Gehringer would probably not play in 1941. (He did, but he had what was by far the worst season of his career, batting .220, nearly 100 points below his career average.) Moreover, everyone agreed that Tiger starting shortstop Dick Bartell was also near the end of the line. The New York Times asserted that Bartell’s “range as a shortstop is down to the width of a dime,” and after a very slow start in 1941, he was released outright by the Tigers in May. (NYT, Dec. 11, 1940, p. 27.)

As a result of the” no trading” rule, Detroit had to rely on its own farm system for replacements in 1941, but few quality players were forthcoming. (Detroit had a small, five-team farm system and no AAA (then called AA) team at all.) Moreover, early in the 1941 season Tiger superstar Hank Greenberg, who had clubbed 41 home runs with 150 RBI’s and a .340 batting average in 1940, was drafted into the United States military after appearing in only 19 games. In addition, pitching ace Bobo Newson , 21-5 in 1940, pitched ineffectively in the early going, and on May 22, sported a record of 2-7 with a 6.05 earned run average.

With its coffers presumably flush from a major league leading attendance of 1.1 million in 1940, Detroit might have been able to find replacements for Greenberg, Gehringer, Bartell, and Newsom, had it been able to deal with the other American League teams. However, thanks to the “no trading” rule, they were barred from even attempting to make any such deals.

On May 15, the 5th place Tigers were permitted to purchase outfielder-first baseman Rip Radcliffe from the last place St. Louis Browns for $25,000, after Radcliffe cleared waivers. It is possible that Radcliffe cleared waivers legitimately — he had finished 4th in batting in the AL in 1939 with a .342 average, but was batting only .282 with just six extra base hits at the time of the trade and no other team may have wanted to take on his salary. However, it is also possible that the other teams felt sorry for the Tigers, who had at that point lost six straight games following Greenburg’s departure for the Army. Although Radcliffe was a career .311hitter, he had very little power, averaging only four home runs a year over his ten-year major league career, and he was hardly an adequate substitute for Greenburg. However, the Tigers apparently had no other alternative.

By the time of the July 1941 All-Star Game break, it was apparent that the rule was having adverse consequences for Detroit that had not been foreseen at the time of its adoption. Moreover, because of the difficulty the Tigers had in replacing Greenberg, the rule seemed almost unpatriotic. The 1941 All-Star Game was, coincidentally, in Detroit, and at the time of the game the Yankees were back at the top of the standings, while the Tigers had fallen to fifth place, one game under .500.

At this point, several American League owners were beginning to have second thoughts about the wisdom of the “no trading” rule. What had been adopted to disadvantage the Yankees was now working to their benefit by effectively disabling the Tigers, the team expected to be the New Yorkers’ principal rival in 1941. At a meeting held in the Detroit office of Tiger owner Walter O. Briggs the day before the All-Star game, Briggs and Yankee president Ed Barrow proposed that the rule be abolished. To secure support of other owners, an agreement was made to delay the repeal until the conclusion of the 1941 season (perhaps to allay any fears that the Tigers might sell their best remaining players to the Yankees). Although three of the eight American League owners reportedly voted against it, the motion was adopted. (NYT, July 8, 1941, p. 22.)

The Yankee absence from the top of the AL standings turned out to be a short-lived phenomenon. They held on to win the AL championship in 1941, and then repeated in 1942 and 1943. After a brief return to the pack during the latter part of World War II, the Bronx Bombers captured American League pennants in 1947, and then 14 times in the 16 seasons between 1949 and 1964 (1949-1953, 1954-1958, and 1960-1964). In spite of this unprecedented dominance, there was no serious effort to reinstate the “no trading” rule, not even after the Kansas City Athletics began regularly trading players like Ryne Duren, Ralph Terry, Hector Lopez, Clete Boyer, Bud Daley, and Roger Maris to the Yankees in the late 1950’s for untested minor leaguers or over-the-hill veterans.

Ironically, the Yankee dynasty of the mid-20th century was finally brought to a close by the team’s decision to stop investing in its farm system and by major league baseball’s institution of an amateur player draft in 1965. When the team’s prominence was reestablished in the mid-1970’s by new owner George Steinbrenner, it was done by taking advantage of new free agency rules which allowed the Yankees to acquire established players at the peak of their careers (like Reggie Jackson and Catfish Hunter), precisely the type of strategy that the 1939 “no trading” rule had been designed to prevent.

In addition to the newspaper articles cited above, statistical and roster information is taken from the Baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org websites and the Sports Encyclopedia Baseball (2007 edition).

Great essay — really enjoyed it.

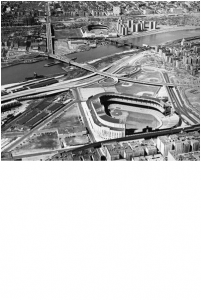

When I described the New York Yankees and New York Giants as “cross-Bronx rivals” in the above post, I misspoke. The teams’ home ballparks, Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds, were located on opposite sides of the Harlem River (see photo added to end of post), but the Polo Grounds were located in the borough of Manhattan, not the Bronx. I should have referred to the teams as “cross-town rivals.”

Special thanks to Catherine Tully for pointing this out.