In his novel 1984, George Orwell imagined a future world where a government at war could switch allegiances with the country’s enemies and allies and a docile public would accept the revised version of history unquestioningly. Orwell, a keen observer of the modern world, recognized that history itself could be manufactured and manipulated in the service of broader purposes.

In his novel 1984, George Orwell imagined a future world where a government at war could switch allegiances with the country’s enemies and allies and a docile public would accept the revised version of history unquestioningly. Orwell, a keen observer of the modern world, recognized that history itself could be manufactured and manipulated in the service of broader purposes.

This morning’s edition of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel contains an opinion piece by Chrisitian Schneider of the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute (WPRI) entitled “Not What They Meant Democracy to Look Like.” In it, Mr. Schneider argues that the current effort to recall Governor Scott Walker and other elected state officials runs contrary to the original intent of Senator Bob La Follette and other advocates of the recall provisions of the Wisconsin State Constitution. His op ed is excerpted from a larger piece that Mr. Schneider has authored for WPRI entitled “The History of the Recall in Wisconsin.”

In the newspaper piece, Mr. Schneider makes the assertion that “a review of documents and press accounts from the time the recall constitutional amendment passed shows that the current use of the recall is far different from what the original drafters had envisioned.” His argument is that the recall provisions of the Wisconsin Constitution were intended to apply solely to judges and state senators, and not to executive branch officials such as the governor, because the two year term of office in place for governors at the time that the amendment passed would have made the recall of a governor impractical.

The historical record is completely contrary to Mr. Schneider’s assertion. Moreover, the evidence that he relies upon is completely inadequate to establish the existence of the skewed original intent that he advances.

The original push to add recall provisions to the Wisconsin Constitution, conducted during the 1911 legislative term, was clearly modeled on the nationwide campaign to adopt recall provisions. I have previously written about the history of the recall movement here. None of the other states that recall advocates in Wisconsin looked to as models in 1911 had exempted executive branch officials from the recall power. Moreover, far from being directed at judges, the original provisions in 1911 were amended in response to criticism so that they exempted judges from the scope of the recall (see page 139 of this history by the Legislative Research Bureau).

Given this record, it is impossible to conclude that the original legislation adopting recall provisions was primarily directed at the removal of elected judges. However, the original legislation was rejected by the voters in 1914, and did not become part of the Wisconsin Constitution. Mr. Schneider appears to argue that when the recall provisions were introduced once again, in 1923 by State Senator Henry Huber, they were no longer intended to apply broadly to all elected officials. Apparently we are to believe that between 1911 and 1923 the intent of the recall provision had changed from an intent to apply the recall to all elected officials except judges to an intent to apply the recall provisions primarily to judges.

Mr. Schneider can cite to no statement from Senator Huber or any member of the Progressive Party supporting this rather implausible conclusion. Instead, he relies primarily on the fact that the use of the recall against public officials serving terms of less than four years (as governors did at that time) would have been impractical.

However, in order to arrive at this rather novel conclusion, Mr. Schneider contravenes two basic tenets of constitutional interpretation.

First of all, it is a mistake to construe the intent of a constitutional provision to be narrower than the plain text of the document. The text of Article XIII of the Wisconsin Constitution provides for the recall of “any incumbent elective officer.” Mr. Schneider would ask us to believe that the 1923 advocates of the recall did not understand the word “any” to include the governor. In so doing, he asks us to substitute his preferred result for the plain meaning of the text. This would be a mistake. In the Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873), the United States Supreme Court made the mistake of assuming that the drafters of the Fourteenth Amendment could never have intended the Privileges or Immunities Clause to have the broad application suggested by its language. As a result, the historian Edwin Corwin observed, this provision of the federal constitution was “rendered a ‘practical nullity’ by a single decision of the Supreme Court within five years after its ratification.”

Second, it is never proper to attempt to divine the original intent of a constitutional provision by relying upon the arguments of its opponents. Almost all of Mr. Schneider’s evidence in support of his proferred interpretation comes from editorials and statements of persons who opposed the ratification of the recall provisions. The statements of opponents are no evidence at all of the intention of supporters. When we seek guidance for the intention of the Framers of the United States Constitution, we look to the authors of the Federalist Papers (Hamilton, Madison and Jay) who argued in favor of ratification. We do not seek to understand the Framers’ intent from the characterizations of the text put forward by those who opposed the Constitution’s adoption. Opponents have every motive to misconstrue the language in order to alarm the public.

George Orwell was amazingly prescient. He understood how the public’s understanding of history could be manipulated by propaganda, and how history itself has no existence except in the minds of the masses. The debate over the Wisconsin Recalls provides all of us with an opportunity to observe the ongoing attempt to re-write history right before our eyes.

My thoughts exactly. I hope you also posted this in the comments section at the Journal-Sentinel.

Thank you, once again, Prof. Fallone.

Thanks Mr. Fallone. It appears that the JS is desperate.

Thanks for some valuable input. Your essays are always instructive and clearly written. Reading them makes me wish I had gone on to study the law.

How is it people can so easily distort basic facts and the historical record, thinking they’ll get away with it, and a newspaper of record can allow these distortions to be printed?

Mr. Schneider has responded to my criticisms of his piece by renewing his assertion that the recall of judges was the primary focus of the 1923 amendment to the Wisconsin Constitution. His review of newspaper articles from that era misses the central fact that an expressed concern over the application of recalls to the judiciary was the primary argument made by persons who opposed the recall power in general. Mr. Schneider does not place his historical sources in the context of this broader debate, and as a result misreads his sources.

The following article by Rod Farmer is instructive, at pages 22 through 28 generally, in summarizing the national debate over whether the recall power should extend to the judiciary in addition to legislative and executive branch officials. After discussing a relevant debate in Congress on this topic, the author states at page 28:

“In these 1911 Congressional and Presidential actions, the recall as applied to non-judiciary officials was generally accepted by the majority. Only the judicial recall was fought over. Progressives might feel the sting of defeat over the judicial recall in this debate; however, the debate was also evidence that the non-judiciary recall was now acceptable in the American political mainstream.”

Mr. Farmer’s full article on the history of the Recall Movement in America, was published in 2001 in the New England Journal of History and can be found here:

http://www.iandrinstitute.org/New%20IRI%20Website%20Info/I&R%20Research%20and%20History/I&R%20Studies/Farmer%20-%20Recall.pdf

I would hope that those who are interested in Chris’ response to Ed’s criticisms will take the time to read it.

The reference to Orwell strikes me as a bit over the top. Chris has offered a more thorough history of the recall amendment than anyone writing about it in Wisconsin has offered and far more than Farmer whose piece doesn’t say much – if anything – about the ratification of Art. XIII, sec. 12.

Here’s where I think that Ed and Chris part ways.

Ed’s criticisms are directed to what that history means to legal interpretation and I agree with some of what he writes. In fact, as a textualist, I would want to argue that, if the language of the amendment is unambiguous, it should be applied as written. On that view, the recall amendment certainly applies to any elected official for any reason.

Unfortunately (in my view), that is not how the Wisconsin Supreme Court interprets constitutional amendments. In stark contrast to its method of statutory contruction, it employs a simultaneous consideration of the text, legislative history and public ratification debate and the most recent legislative enactment interpreting the amendment’s scope. See Dairyland Greyhound Park v. Doyle, 2004 WI 52.

So, while I am very sympathetic to Justice Scalia’s view that much of the practice of legislative history involves little more than looking over a crowd and picking out your friends, we have to see what it tells us.

On that question, I don’t think that looking at the recall movement nationally carries much weight. What “Progressives” supported is not synonymous with what Wisconsin voters – who seem to have rejected the Progressive position in 1914 – thought they were approving.

Looking at Wisconsin, things like newspaper articles have frequently been used by the court to assess the public ratification debate. With that in mind, I think Chris’ exposition of the history suggests the following: Few people seem to have thought that the recall amendment would have much impact on executive officers and most legislators because they were elected for two year terms. Opponents used this to argue that the amendment was not worth the candle (or dangerous as applied to judges.) Proponents used the same fact to argue that it would not be resorted to with frequency.

(I do not agree, incidentally, that assessing the public debate is always limited to what the proponents had to say. Depending on how proponents responded and the relative quantity of speech for and against an amendment, opponents’ speech might matter. But that’s a topic for another day.)

The expected scope of the recall power changed when – probably without much thought about the impact on recalls – the term length of executive officers was extended.

Is this enough to make a legal argument that Art. XIII, sec. 12 applies only to judges and state senators?

I don’t think so. But it’s not because judges were excepted from the original failed amendment. There were two different amendments passed by two different legislatures over ten years apart. To suggest that one says much about the other requires passing by an awful lot of faces in Scalia’s crowd. As a practical matter, limiting the right of recall to officials who had more than a year in office did have the effect – in 1923 – of making judges a more likely target of recalls (and making most state officials unlikely targets).

But even under Dairyland Greyhound Park and its antecedents, I don’t know that arguments about the likely impact of recalls can be readily translated into arguments about the scope of the language authorizing them.

But Christian Schneider is not a lawyer and I don’t undertand him to be making a legal argument. He is trying to suggest that the use of recalls to accelerate the election cyle due to policy disagreement has little support in the history of its adoption or its use over the years.

You can disagree with that – or try to argue that Walker’s policy changes are somehow unprecedented – although that argument would be more persuasive if recall proponents emphasized or even talked much about collective bargaining.

You can argue that Chris missed some relevant history regarding adoption of the recall power in Wisconsin, although no one here has done that.

But I don’t think that his policy position – and the reasons that he offers for it – are even close to Orwellian.

Returning to the law, I have problems with most legal proposals to limit recalls because it is hard to think of a judicially manageable standard that would do the trick. We – or at least I – want it to be used only in exceptional circumstances and not in cases of mere policy disagreement. But that doesn’t seem like a standard that courts can apply.

Chris’ argument that, as a matter of policy and historical precedent, what is happening now is something that we have not seen before is another matter. I tend to think that the remedy for promiscuous use of the recall power is political. If the current recalls succeed, we can expect to see another tool added to the endless campaign.

Rick:

You confuse a simple question.

Mr. Schneider asserts that the original intent behind the State Constitution’s recall provisions differs from the the current use of the recall power. If he is to make such an assertion, and he did on the front page of the Crossroads section of the newspaper, it is necessary for Mr. Schneider to define the original intent behind Article XIII. In this task, he fails.

From newspaper articles and opinion pieces expressing criticism of the use of the recall against judges, Mr. Schneider infers that the original intent of the recall must have been the creation of a power to remove judges. In fact, the plain text of Article XIII, the history of the 1911 legislative debates, and the national debate over recalls all demonstrate that the intent of the recall power was to allow a broad scope of removal of executive and legislative branch officials, with Article XIII extending that power to judges contrary to the misgivings of some.

Therefore, the current use of the recall power to seek the removal of Governor Walker and the other executive and legislative branch officials presently subject to recall election is fully consistent with the original intent behind Article XIII.

You characterize Mr. Schneider’s argument as being that “Few people seem to have thought that the recall amendment would have much impact on executive officers and most legislators because they were elected for two year terms.” You are correct that this is what Mr. Schneider asserts. The problem is that he provides no evidence supporting his conclusion that “few people” held the belief that the provisions would be used against executive officers. At best, he has demonstrated that a few critics of the proposed amendment expressed their belief that any such impact would be minimal.

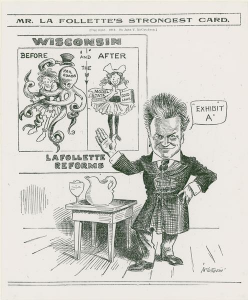

In regards to your suggestion that we ignore the national debate over recalls, I am afraid that it is not that easy. The Recall Movement is called a “movement” because it was just that: a national movement that sought to bring structural change to state constitutions across the country. You can’t just wave away twenty some years of public debate (a debate in which Senator Bob La Follette was a leader).

Finally, you find my George Orwell reference to be “over the top.” I don’t. Let’s just add this to the long list of items on which we disagree.

Even if everyone agreed with Mr. Schneider that the clear, original intent of the Wisconsin recall provision was that it would not apply to officeholders with two-year terms, then that barrier has long since been removed with respect to the offices of governor and lieutenant governor, who of course now serve four-year terms.

Also, it’s interesting that Mr. Schneider and other think tankers had no comment on the legitimacy of the recall effort against Scott Walker’s predecessor in the office of Milwaukee County executive, another four-year executive position. Only now has such application become an issue. How convenient.

Finally, I submit that the Journal Sentinel’s previous echoing of arguments from Rep. Robin Vos and other conservatives — namely, that recalls were only intended to redress “misconduct” by public officials — is another example of historical revisionism. Apparently, that meme hasn’t gained enough traction on its own, and so the mining operations continue.

Ed

The point he raises – and as I say it has more force as a policy than a legal argument – is that no one thought that the recall provision that was passed in Wisconsin in 1926 (as opposed to the one that was defeated in 1914 or that the Progressives were able to pass elsewhere) would have much impact on most nonjudicial officeholders because of the combination of a one year waiting period and two year terms of office.

Pointing to the national debate isn’t much of a response to that. It takes the issue to a level of abstraction that ignores what actually happened here – as opposed to what the Recall Movement wanted to happen.

But, again, I don’t think that a legal (as opposed to political) argument that Art. XIII, sec. 12 is limited to judges or two year office holders or by the purpose of the recall would be successful. Since this belongs on the shorter list of things that we do agree on, it might be well for me to stop.

Rick:

I am not sure that you are doing Mr. Schneider any favors.

You have now moved from “few people thought” to “no one thought.”

These are not legal arguments, nor are they policy arguments. These are assertions of fact.

Mr. Schneider claimed to be writing history. My point is, and always has been, that he provides no evidence which actually supports his so-called original intent. At most, he claims that the opinions of a few critics are representative of the majority of the voters.

He can write all of the opinion pieces that he wants. He just can’t try to pass them off as history.

I certainly am not in possession of any information that would contribute much to this debate, except to note that it appears there was significant disagreement and uncertainty about the full impact of the recall amendment when it was ratified in Wisconsin. This is no surprise. Much of the debate about which sources to read and the weight to give them is characteristic of any attempt to divine a unified Original Intent to a legislative act that was a compromise. The only thing indicating –- with authority –- what was intended is the actual language enacted. The different parties agreed to that much.

Everything else we do here is surmise, and I must agree with J. Scalia (note the date): much of the practice of legislative history involves little more than looking over a crowd and picking out your friends. As Prof. Esenberg writes, “we have to see what history tells us”, but when it tells us that there was a significant lack of agreement, then we should hew to the text unless facts compel otherwise.

The text of the Wisconsin recall amendment clearly does not exclude governors from its reach. History is ambiguous, so it does not compel us to jettison the plain meaning of the text.

sean s.

Sean:

You are quite right. However, we should not make the mistake of concluding that the indeterminacy of knowledge means that we do not know anything.

We know that the recall provisions were not intended to advance corporate interests over the interests of individuals. We know that the recall provisions were not intended to be limited in use to the removal of those officials who are convicted of crimes or ethical transgressions. And we know that the recall provisions were not added to the Wisconsin Constitution for the primary purpose of removing judges.

I have discussed the dangers of this flaw in logic before (in a humorous vein):

http://law.marquette.edu/facultyblog/2011/10/28/the-bride-of-dracula-a-halloween-story/

Professor Fallone, you are quite right; indeterminacy of knowledge does not mean that we know nothing, But, depending on the situation, it does mean we don’t know enough to regard some proposition as true.

I will stipulate to the things you cite as known about the recall provisions of the Wisconsin Constitution; we also know that nothing in the text of the provision contradicts any of those assertions. Whether history conclusively supports those assertions is not decisive when the assertions are in accord with the plain text. In this instance, we are in the same position we would be if no historic records existed at all; we’d be relying on the plain text alone.

In this instance, the history only becomes decisive if it strongly contradicts one, some, or all those assertions above; in this instance it does not. Unless or until it does, the plain text reading should be decisive.

I do not object to considering the history of the ratification of this or any other provision, but I do think that the results of such considerations must be kept at some reasonable remove because they are prone to abuse. Isolated comments and strained inferences can be (have been) given far more authority than they merit under the rubric of Original Intent. Certain persons (the “friends” J. Scalia referred to) are given authority they do not deserve, as if their opinion was law. I appreciate the use of legislative history, but sometimes it becomes worse than a duel of expert testimonies, sometimes it seems to be a duel of séances.

The indeterminacy of knowledge does not mean we know nothing, but it does mean that some degree of uncertainty persists. We still must act; uncertainty counsels caution, not hesitancy. Caution demands we remain cognizant of our uncertainties instead of disregarding them.

Bravo!