Federal Indian Law—the legal provisions and doctrines governing the respective statuses of, and relations among, the federal, state, and tribal governments—is replete with seeming anomalies when compared to the background of typical domestic law in the United States. The purpose of this post, and of the series of which it is a part, is to identify and examine such anomalies in an effort to acquaint readers with the metes and bounds of Federal Indian Law, while shedding some light on the origins and perhaps the future of this unique legal realm.

Federal Indian Law—the legal provisions and doctrines governing the respective statuses of, and relations among, the federal, state, and tribal governments—is replete with seeming anomalies when compared to the background of typical domestic law in the United States. The purpose of this post, and of the series of which it is a part, is to identify and examine such anomalies in an effort to acquaint readers with the metes and bounds of Federal Indian Law, while shedding some light on the origins and perhaps the future of this unique legal realm.

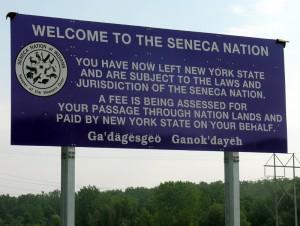

The prior post examined one such anomaly, namely, the permissibility of the government’s differential treatment of Indian tribes and their members despite the U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection. In this, the second installment in the series, another topic of significant contemporary interest will be surveyed. This is the oddly diminished character of Indian tribal sovereignty and, in particular, the extent to which tribes, in their own territories, lack criminal and civil authority over non-Indians or non-tribal members.

The capacity to enact and enforce laws is, of course, one of the hallmarks of sovereignty within the Western political tradition. This includes both criminal laws and civil laws, the latter often being divided into powers of regulation, taxation, and adjudication. It is typically accepted, moreover, that the reach of a sovereign’s laws extends along two axes: citizenship and territory. That is, the sovereign has the authority to govern not only its citizens but also all others who enter its territory. Thus, for example, inquiries into the jurisdiction of courts over a person or his property ordinarily entail an examination of the person’s citizenship and/or the relationship between the person’s conduct or property and the territory of the sovereign to which the courts belong.

In recent decades, however, Indian tribal sovereignty has increasingly been confined to a single axis—that of citizenship—leaving tribes largely powerless to enforce their laws against non-Indians who, within the tribe’s territory, commit criminal conduct or engage in activities that would normally be susceptible to regulation, taxation, or adjudication. Perhaps surprisingly, the institution primarily responsible for this diminishing conception of tribal sovereignty is not Congress, which the Supreme Court has repeatedly described as having “plenary power” over Indian affairs, but rather the Court itself.

The backdrop to the Court’s activity concerning tribal jurisdiction over non-tribal-members consists of a blend of ideology, history, and legal doctrine. Upon European contact with the indigenous peoples—or “discovery” of their lands—the discovering sovereign, whether England, France, or Spain, is said to have acquired certain powers and rights over the indigenous people and their territory, while the indigenous people are said correspondingly to have lost certain powers and rights. According to this view, the American Indian tribes were left with a diminished form of sovereignty, still including the power to enter into treaties, for example, but no longer including other key sovereign prerogatives. In relation to the U.S. government, which effectively stepped into the shoes of the European sovereigns, the tribes (to quote the Court) “forfeit[ed] . . . full sovereignty in return for the protection of the United States.”

Framed as a matter of legal doctrine, the Court has stated that Indian tribes retain all dimensions of their original sovereignty except for: (1) those ceded by the tribe, e.g., by treaty, (2) those expressly taken away by Congress, and (3) those inconsistent with the diminished sovereign status of tribes, which Chief Justice John Marshall famously characterized as “domestic dependent nations.” It is this third, somewhat circular exception where the Court, by its own lights, determines which powers tribes retain and which powers they no longer possess. To be sure, the Court’s framework can be deceptive, for the exceptions—i.e., the powers that have been tribally ceded, congressionally eliminated, and judicially declared as being lost—probably far outweigh the general rule—i.e., that tribes retain all powers not falling within the exceptions.

Employing this third category, the Court’s modern delineation of tribal jurisdiction over non-Indians, or more broadly over non-tribal-members, essentially began in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, issued in 1978. Oliphant involved a tribal prosecution of two non-Indians, one of whom had allegedly assaulted a tribal officer and resisted arrest and the other of whom had allegedly damaged tribal property and committed reckless endangerment. The Supreme Court responded with a categorical declaration that “Indians do not have criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians absent affirmative delegation of such power by Congress.” The Court reasoned that such jurisdiction, though neither ceded by the tribe nor expressly extinguished by Congress, would be inconsistent with what the Court believed to be Congress’ historical understanding, and further that such jurisdiction would be unfair to non-Indian defendants unfamiliar with tribal “customs and procedure.”

The first civil-law counterpart to Oliphant was issued just three years later in Montana v. United States, which involved the Crow Tribe’s efforts to regulate non-Indian hunting and fishing on non-Indian-owned land within the tribe’s reservation. In response to the Crow Tribe’s assertion of authority, the Supreme Court articulated a rule less categorical than that of Oliphant but nonetheless quite powerful: tribes are presumed to lack regulatory authority over non-Indians within their reservations, at least for conduct on non-Indian-owned land. This presumption may be overcome, and the tribe may be able to regulate non-Indian conduct, if the tribe can demonstrate either (1) that the non-tribal-members have “enter[ed] consensual relationships with the tribe or its members, through commercial dealing, contracts, leases, or other arrangements,” or (2) that the non-tribal-members’ conduct “threatens or has some direct effect on the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the tribe.”

The Montana case involved tribal regulation of non-Indians on non-Indian land, and thus Montana’s main rule and its two exceptions technically applied only to comparable scenarios. Beginning in the mid-1990’s, however, the Court issued several decisions that have since extended the Montana framework to both tribal adjudication and tribal taxation and, moreover, have diminished the significance of the ownership status of the land (i.e., whether or not it is non-Indian-land) within the reservation. At the same time, these rulings have revealed that the two exceptions to Montana’s main rule, especially the second, are narrower than their wording might suggest. Thus, while the Montana framework for civil jurisdiction is not as black-and-white as the Oliphant rule for criminal jurisdiction, from a pragmatic perspective the consequences of the two approaches may often seem indistinguishable.

So why has the modern Court so drastically diminished the territorial axis of tribal jurisdiction, leaving tribes, most of the time, with jurisdiction only over their own members? Such an arrangement is not found elsewhere within the United States—whether one considers the federal government, the states, or even counties and municipalities—nor is it readily found elsewhere outside of the United States, except perhaps in extreme situations such as post-war occupation or the international refusal to recognize a geopolitical group’s sovereignty in the first instance.

The notion that the Court is merely giving effect to historical congressional understandings is not particularly convincing, especially in the civil jurisdictional context (Montana and subsequent cases). Indeed it is difficult to square such a notion with the second method by which tribes may no longer possess a given power, namely, that Congress has expressly taken that power away. One would that think Congress’ failure (or choice not) to extinguish a power expressly would virtually preclude a judicial ruling that such a power has been lost because Congress appeared to believe (but did not say) that the power did not exist.

A more plausible rationale, perhaps, is that the Court’s members harbor serious skepticism about the structure, operation, and integrity of tribal courts or tribal governments more generally. Some of this skepticism may be well founded, but it may also be beside the point. If tribes, like states, possess a genuine species of sovereignty, then a more robust degree of territorial jurisdiction ought presumptively to be recognized (and, correspondingly, ought not to be easily diminished or extinguished or lost). If and when problems of tribal court structure, operation, or integrity arise, they can be addressed on a case-by-case basis, much as the problems with some state court systems have been addressed over the nation’s history. Of course, the potential issues raised by extensive tribal jurisdiction should not be minimized, and they are in some instances not simple and possibly quite serious. But essentially stripping governments of much of their jurisdiction, in response to the prospect of such problems, hardly seems a proportional—and certainly not a conservative—approach.

This is an extremely well-written article. I have often been puzzled by the “sovereign nation” aspect of Indian law. This blog helped me understand it a bit better. That said, Indians don’t seem to be as sovereign as they should be.